by Sophie Lewis |

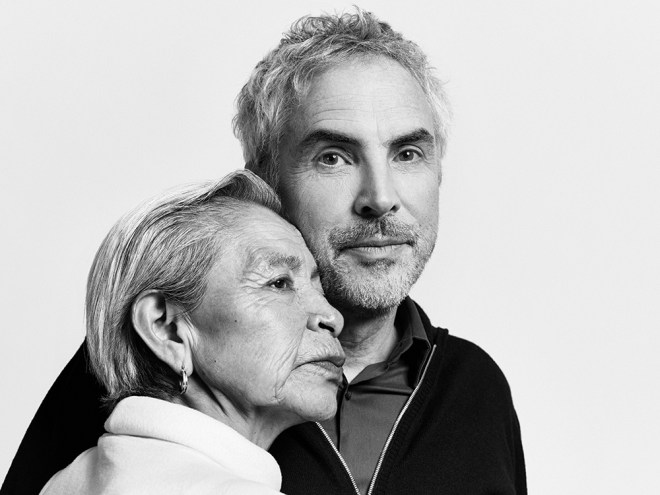

Decades ago, a white settler, Alfonso Cuarón, promised a colonized indigenous Mixtec woman from Oaxaca, Liboria Rodríguez, that he would take her on an airplane; that he would give her the world. Now, in 2019, the newspapers are beaming that this promise has been made good. The elderly Rodríguez has been given occasion to travel. She’s been interviewed, she’s been invited to premieres, she’s been on set with the great Alfonso Cuarón. Why? Because the tantrum-prone boy whose ass she wiped professionally every day in Mexico City has released an internationally acclaimed film depicting, of all things… her!—at least, her labor in the bourgeois household he grew up it—or, more accurately, a slice of that labor.

Roma has been billed as an edifying exercise in perspectival reversal. The great auteur, so we’re told, decided to make his own child-self marginal to his gorgeous black-and-white cinematic childhood memoir. The ‘star’ of this ‘cozy blanket of a film,’ in other words, is supposedly the maid. While some prestige western critics have questioned this premise (calling Roma “a tone-deaf paean to servitude”), it has mostly fallen to actually marginalized voices, such as the Salvadorean feminist @Dichosdeunbicho – who saw an unmistakable el pobre indio stereotype instead of a “complete and complex human being” – to point out that it is false.

Others, such as Ignacio Sanchez Prado and Ana Katarina Zatarain, have been more diplomatic with their criticism, arguing that, despite its undeniable “class trouble”, the film “centers the Mexican experience” rather than the American gaze; and that “a film in which Cleo ‘had a voice,’ whatever that could have meant, would altogether miss the point of her constant dehumanization.” Carlos Aguilar offers that Cuarón is, at least, “never facetious” about inequality. Inkoo Kang poses, but does not answer, the question: “Can any movie made amid affluence—which, it’s no secret, is most movies—fully capture the sentiments and struggles of the working class?”

The unspoken follow-up question to that is, surely: If not, why should any such movie be made at all? For my part, I’d far rather consume Yalitzia Aparacio’s world-shattering talent via some other vehicle.

Leaving the Dirty War raging largely off-stage, Roma (2018) chronicles a temporal sequence in 1970 and 1971 in which Rodríguez was even more instrumental than usual to her employers. During that particular period, when Cuarón’s dad walked out on his wife and kids, it was the nanny’s practically ceaseless work that enabled all her charges to survive the abandonment and, in particular, allowed Cuarón’s mother to reinvent herself—to have a narrative arc.

The woman who Cuarón purports the film is really about does not get a narrative arc.

The woman who Cuarón purports the film is really about does not get a narrative arc. Certainly, a man abandons her, as well. A slum-dwelling martial arts fanatic called Fermín (Jorge Antonio Guerrero) gets her pregnant and then threatens to kill her if she tries to involve him in the baby’s life. Incidentally, Fermín later turns out to belong to the elite death squad responsible for the deaths of communist students: Los Halcones (whom the film represents as getting training, not only from the CIA, but from the “Mexican Houdini” and muscle man, “Professor Zovek”).

The superficial parallel in the women’s experience of male desertion is presumably why the lady of the house (“Señora Sofía”—Marina de Tavira) has a drunken lapse in which she imagines her maid (“Cleo”—the Rodríguez figure—played by the first-time actor Yalitza Aparicio) will extend some kind of sisterly solidarity. When she is ditched by her moneyed husband, a professor of a different kind, Sofia slurs the following sloppy curse at her employee: “No matter what they tell you… women, we are always alone.”

Bullshit. It turns my stomach that ‘feminist’ reviews of Roma have cited this moment as somehow profound, even going so far as to call the two women “sisters in solidarity” and claim that “each of us is represented in Cleo and Sofia, in their unwavering and unstoppable support for one another.” In myriad different ways, the film itself shows that this white-feminist sentiment, offered down nihilistically from one woman to another who has nothing in common with her, is absolute nonsense. But does the film know that it shows it? No.

How much is Cleo getting paid? The question of women’s earnings, in Roma, only arises in connection with the señora, not the niñera. In a conversation that lands somewhat hilariously on millennial ears, Señora Sofía announces that she is leaving the biochemistry industry to go into the more lucrative business of (wait for it) publishing, the better to support her four children. “We have to stick together,” she tells her assembled brood—including Cleo, who has been pressed to “voluntarily” join them in Veracruz.

The beach holiday turns out to be a parental ruse by which the children could be temporarily evacuated from their home to allow their daddy to slip in and take away his bookcases. The adult Cleo, according to the movie, is just as innocent of this plan – bless her simple heart! – as the children are; and just as unsuspecting of the reality of the divorce.

Thus, Cleo, in Veracruz, ends up working doubly hard to manage the children despite Sofia’s decree that they are not allowed to “make Cleo work” because she is on holiday. She is working very hard, one might say, at the appearance of not working at all. At this crucial time in the family’s history, when the conjugal union was falling apart, it was imperative that the labor of kinship-maintenance – which racialized reproducers have always carried out on behalf of the white Family – be utterly naturalized and concealed. The image of the six of them, tightly clasping each other, all grouped around a collapsed Cleo kneeling on the sand, represents this theoretically wonderful “sticking together”, this labor of love. I find it ghoulish.

“They call it love, we call it unpaid labor,” posited Wages for Housework in the early 1970s, pioneering their militant revolutionary perspective on the (paid and unpaid) work of social reproduction under capitalism. And I’d submit that it’s worth keeping the disciplinary function of ‘love’ ideology in mind as we load up Roma on Netflix, in the wake of endless asinine reviews declaring this 1970s retrospective “both [Cuarón]’s most personal film and his most universal in that it’s all about love” (or similar). “Roma is a love letter to your family’s maid, Libo,” declares, for instance, The Guardian, inadvertently reminding us how violent love letters can be.

Is it supposed to have equalized the playing-field, somehow, that the dueña de la casa didn’t fire Cleo for being pregnant, instead securing her access to the highest-end medical care? If so, then this is a deeply constricted vision of love as a reciprocal bond of noblesse oblige and servile devotion; a veritable travesty of the decolonial form of love the Chicanx philosopher Chela Sandoval theorized as a “hermeneutics of social change” in Methodology of the Oppressed.

Mine is not a critique that depends on what the real-life Rodríguez thinks of the movie, though what she thinks of the movie would certainly be good to know. The media circus implies – perhaps taking it for granted – that the elderly ‘Libo’ likes it very much. Actually, from the publicly available quotes, this isn’t at all clear. “I feel very proud that the film is producing these reactions,” she’s on record as saying. “If I could be like a messenger peace dove that goes all over, that would be my dream, because that’s what I feel inside of me. I would like to do something for everybody in the whole world.”

It’s almost as if nobody has straight up just asked her what she considers to be the merits of the film. But… “she cries a lot,” professes Cuarón, proudly. “The beautiful thing is that when she cries it’s not because of what is happening to her, it’s because she’s concerned about the children. She’s not focusing on her own pain.”

Beautiful, huh? Is it beautiful that human beings labor as servants? In Roma, it certainly is. We see hypnotically aestheticized, oiled monochrome visions of prepubescent siblings (and adults) ordering a racialized docent around while sweetly chorusing “we love you, Cleo, we’d miss you if you weren’t here”. She says “I love you, too,” it’s true – even behind their backs, even of the worst behaved of them. But isn’t that precisely, as the Italian autonomist-feminists saw, what’s so damn evil, so damn insidious, about the conjuncture?

One reviewer declared that, by the end of the movie, Cleo has “finally joined the family.” Sure. And this is precisely why a horizon of family abolition remains necessary in the 21st century. She picks them up from school, she cares for and cleans up after their dog, she dresses them, she sings them lullabies at night and wakes them up every morning with whispered rhymes. She saves them from drowning, for god’s sake, despite not being able to swim herself. The dog shit, pressed under tires, squished underfoot, just keeps on keeping on, dotting the courtyard in great dollops, winning the war against Cleo’s broom, her soapy pail.

It is sick to make excuses for this sacrificial kind of beauty, this making-beautiful of class and coloniality.

Of course the Cuaróns were lucky to have her. Hers is the kind of amazing, and yes, in some ways, beautiful, labor that sustains the world-as-it-is while immanently suggesting a wholly different kind of world by virtue of its comradeliness. But it is more than complacent: it is sick to make excuses for this sacrificial kind of beauty, this making-beautiful of class and coloniality.

One reviewer muses: “If we never quite get to hear what Cleo makes of her lot, that’s indicative of an entrenched social system that gives men like Cuarón greater powers and outlets of expression.” Nevertheless, he says, giving the film five stars, it “doffs its cap” with “adoring awe” to the “unseen woman” and her “drudgery,” serving as a “belated valentine” and an “intimate, fine-boned memory-piece,” an “act of noticing.”

Roma does not “notice” that the ideal of care for children (of all classes) serves to mystify the wage relation. The notion of ‘family’ is deceptively spread across that wage relation so as to justify the deep, structural stratification in the way children are made and cared for under capitalism. I do not agree that it is beautiful (if indeed it is true in Libo’s case) when proletarians internalize their domestic work, their geographic and spiritual dispossession, such that they do not know how to “focus on their own pain”.

Then again, there is one moment when Cleo indirectly speaks about her pain. It is a moment in which she and the seemingly youngest, weirdest child – not the stand-in for Cuarón, but his brother, who apparently referred constantly to a past life he had lived (“when I was old”) – are lying flat on their backs on the roof, crown-to-crown. Cleo, the stereotypical silent and stoical subaltern, is taking a break from doing the laundry to join this child in a game involving being dead. She leaves off singing along to a pop song playing on the radio whose lyrics include the line “But I was born poor / And you’ll never love me”. Closing her eyes, resting her bones, she plays dead. “I like being dead,” is what she says, in this moment.

The words hang in the air like a gas. A particularly irritating reviewer was symptomatically at pains to report that there isn’t “anything bleak or creepy in the[se] words.”

It is infamously capitalism’s new mantra: do what you love, love what you do. In this sense, it seems to me that “I like being dead” is one of the many moments when Cuarón’s film shows, even if it doesn’t know, the obliterating misery that is class subjection. As I see it, it’s a telling accident, an unwitting irruption, which exposes the mockery that work, in its unfreedom, necessarily makes of the idea of “love”. This scene, among others, confirms that Roma is smarter that itself—smarter, certainly, than its director has the power to understand.

Asked by the starstruck press what motivated him to make Roma, Cuarón has actually been surprisingly candid: “It was probably my own guilt about social dynamics, class dynamics, racial dynamics. I was a white, middle-class, Mexican kid living in this bubble.” More than just guilt, in fact, the New York Times suggests that what he feels about his privilege is actually “disgust”. An object-lesson, if ever there was one, that liberatory, comradely politics do not – by definition – emanate from a bad conscience.

Liberatory, comradely politics do not – by definition – emanate from a bad conscience.

Cuarón used to call the nanny “Mamà”. Note, though, she is not included in the noun “family” when he explains: “The family can have all the damn lights on all day, and it’s her job to go around turning them all off while the family is upstairs, but they” — the pinche gata (a classist, misogynist slur for domestic workers in Mexico City) — “are not allowed to use electricity in their own room.”

Yes, Cuarón used to call Libo “Mamà”. But, rather than passing the proverbial mic to the subaltern who mothered him, Cuarón elevated the voice of his biological, legal mother. He made art about, as he put it, “wounds that were personal – family wounds”. One imagines he is perhaps talking about his parents splitting up. But no:

“I realised these were wounds that I shared with many people in Mexico. And then I came to the conclusion that they are wounds shared by humanity.”

Is it possible that Cuarón really thinks that, despite having been in the “bubble” that was his social class, the historic experience of life in Mexico City in 1971 is somehow equally Cleo’s and his to tell? Do we somehow all “share” equally in the pain of earthquakes; of state-backed fascist massacres such as the Halconazo; of land enclosure and dispossession? (Cleo’s Mixtec mother has her land stolen by the government.)

Maybe, if you actually think this, then it actually makes sense to make a movie in which the maid-cum-nanny has no more history, personality, political awareness or aspiration than do the bratty seven-year-olds she soothes and tolerates—and then to call it all an “homage” to her, a “tribute” to “her perspective”.

Strangely enough, it was no less of a communist vehicle than The Economist magazine that spotted that Cuarón makes Cleo – the ostensible star of his movie – “mute”. Writes ‘Prospero’: “He cannot imagine Cleo wanting to be anything more than a faithful servant.” Sofia, the white lady, in fact, “gets more lines in one scene than Cleo gets in two-and-a-quarter hours.”

So, while some critics have noticed that Roma is “little more than the righteous affirmation of good intentions,” overall, the idea that the movie constitutes a legitimate “exorcising of guilt” and an ode to universal human suffering has deeply impressed Anglophone cultural gatekeepers across the board. Reviews have praised, for instance, the “painful and poetic backstory” and “sea-like sway of his remembrance”; gushing that Cuarón clearly “never left this place, its women and its love”; that “trying to review it is a bit like trying to review all of life”; and that “Roma, at its most transcendent, captures” the fact that “Life is hard. But here is everyone.”

Everyone is decidedly not here. The landless peasants, the communists, the indigenous rights activists, the domestic workers’ movement, those seeking justice in the wake of the 1968 massacre—none of them are there. Cleo herself is not substantively there, for crying out loud. Roma presents literally nothing about her desires; her opinions; or her past.

I mean, make a film about your boyhood, why not. Book-end it with the image of a plane leaving its frothy trail in the sky, an image we saw first reflected in the courtyard soap-suds. But then buy a fucking plane, or something, and hire a pilot, and sign it all over to the person whose deprivation made your career possible. Give all your money to the revolutionary domestic workers in Mexico City. And ask yourself whether Liboria Rodriguez might prefer, once you’ve made her rich, that you leave her alone. Ask yourself whether you’re not, perhaps, only making her work again, with your “belated valentine”: making her work and work, even more, in her old age, to promote your bloody movie.

***

Sophie Lewis (@reproutopia) is an editor at Blind Field and the author of Full Surrogacy Now. You can support her writing here.

Love this. Regrettable that it was left to reviewers to humanize this poor woman after everything she has been through, and typical bourgeois depravity that even the supposed liberal ones still desire no more for this tormented soul than to keep laboring in perpetuity like the original zombie myths.

LikeLike

Apologies for leaving this so long, Rifka, and thank you for your kind and insightful comment! If you ever fancy submitting an essay on “zombie care work” for consideration here at Blind Field, please don’t hesitate 🙂

LikeLike

I believe this reviewer is trying to do the right thing by pointing out the ways in which Cleo’s life is unfair. As a poor, indigenous woman, Cleo never had a chance to aspire to greater things. That much is true.

But in doing so, she also is missing other important things.

Cuaron does a good job in pointing out subtleties, and he is not afraid to look himself, and his family, look bad.

Yes, they all love Cleo. That is apparent. The kids are very attached to her. And for the most part her bosses are kind to her.

But they are also completely unaware of how assymetrical that love is. The lady of the house, who is having a bad time coping with her husband leaving her, snaps at Cleo several times without justification, and Cleo just shuts up and takes it, as she is expected.At another she is asked to carry the family’s luggage, eventhough she is pregnant.

The movie is full of this moments, in which it is clear that while everyone appreciates Cleo, and that they are willing to be kind to her, that her needs will always come last. But the reviewer seems to be under the impression that this somehow happened by accident. As if Cuaron was some kind of hack, who absentmindedly let things slip on.

Perhaps. But I seriously doubt it. After years of hearing from him in interviews, both his, and from other actors and directors who colaborate with him,I have come to the conclusion that he is quite obsessive about what he puts in his movies. Specially in his own movies, where he has full creative control. So no, in my opinion, Cuaron didn’t let anything slip on. Cuaron put all those mindboggling, heartwrenching scenes there, to make a point: Even if we are wellmeaning, we often lack selfawareness. In this partuclar case, eventhough he loved his nanny, and she loved him back, that love was asymetrical, and as such deserves some thought.

In the end, it is fair to question if love can arise under this circumstances, or if the underlying unequality is like some sort of poisoned soil, that no matter what you do, will either kill or forever limit what you can grow there.

This reviewer seems to think not, and that is fine. Although it concerncs me it angers her that people like Cuaron (or me, for that matter), think that in spite of our differences, we have enough capacity for love and compassion, that a few shared life experiences can lead to love and friendship, even if that love and friendship needs some qualification.

LikeLike