By Tara Needham |

This piece is a part of an ongoing series on housework

“Domesticated Medusa,” Acrylic and transfer on wood panel, 46 x 34

I was eleven when my mother announced her housework strike. She made her declaration at the kitchen sink, tossing a dishrag onto the plastic drying rack, literally throwing in the towel. Immediately, I ran to my bedroom and wrote about it in my Little Twin Stars diary:

10/15/84. Dear Diary: Guess What? My Mom just came down the steps and told us she is on strike for the rest of the week. It’s gonna be neat!!! We all have to make our own dinner and everything!!!! I sure hope I can manage. Love Tara

It’s. Gonna. Be. Neat. That’s the reaction of the people-pleasing golden child I was then – as well as that of a good little housecleaner in training. Though not grasping the strike as a collective action aimed at the larger political economy, I took it as an adventure, as a kind of dare. My excitement was attached to something greater than the strike’s novelty or challenge: I hoped it would at least change the emotional economy of our house. Mom would be happier and, having liberated herself, she would liberate us all from the tension and stress of her being overworked and underappreciated. Even then, I sensed the housework strike as a form of feminist self-care, one that might free us all from the orbit of my mother’s misery. I was eager to do my part.

•••

The increased attention to women’s unpaid domestic labor in the 1970s and 80s is, no doubt, attributable to the International Wages for Housework Campaign, founded in Italy in 1972 by Selma James and Silvia Federici, among others. Their Marxist-feminist critique of political economy argued that women’s unpaid labor made capitalism possible, and was the condition for the reproduction of all labor. Thus, recognition of, and compensation for, women’s household and emotional labor was imperative for both an effective critique of capitalism and the achievement of gender equality. The Wages for Housework movement was instrumental in lobbying the United Nations to encourage nation states to consider women’s unpaid labor as a part of their GNP, a commitment the U.N. announced in their July 1985 report, entitled “Forward Looking Strategies.” [1] This report also included a worldwide call for “Time Off for Women” to take place on U.N. Day, October 24, 1985. This would come to be known in the press as the “housework strike.” In more than 18 countries, including the United States, women were encouraged to leave their homes and workplaces, to gather in public spaces, and to call the press and political representatives in order to draw attention to their various forms of labor, much of it unpaid and performed in the home. [2] The call was modeled on Iceland’s highly successful “Women’s Day Off” ten years earlier, when 90% of Icelandic women refused to do household work or to report to jobs outside the house. [3]

Was my mother ahead of her time? (Technically, yes—by a year!) It wouldn’t surprise me if her strike had been informed by this growing societal awareness of the uneven distribution of household labor – as well as a direct reaction to her lazy husband and kids. The personal is political is personal, rinse, repeat. She worked full-time as a fifth-grade teacher, raised three children, and has been a member of the American Association of University Women for decades. Even in a household not well-versed in labor history, one short word – “strike” – conveyed so much, and brought a sense of formality and strategy, if not collectivity, to our door. Her strike may not have made the papers, but it left its mark in my diary and on my little literary mind.

…

I am forty when I contemplate my own housework strike. I have two cats, no kids, and an enlightened, feminist life partner. Our first year of cohabitation is an extended honeymoon of wine-fueled conversations critiquing patriarchy, sexism, and racism. Concluding typically, I now realize, with me washing the wine glasses. During this time, we distribute household chores in ways that buck gender conventions. He does the food shopping and cooking, both of which I hate, while I do household repairs, replacing pipes under the kitchen sink and climbing onto the roof of my two-story house to clear the leaves. When his parents visit, he and his mother fuss in the kitchen, while his father and I rummage through toolboxes, trim hedges, and fix faucets. He’s not a neat freak, but after residing with an actual hoarder (ask me about cohabitation with more than 500 Homies figurines and the packaging they came in), our living situation was at more-than-acceptable adult levels of cleanliness and order.

During that first year, I am home a lot under the guise of writing, while teaching a class here, and working part-time there. I happily clean and tidy the house. I think of this less as housework and more as productive procrastination, a break from intellectual labor. Sometimes I frame it as physical exercise, especially if I mop or vacuum using a particularly deep lunge technique. And I am really sold on the feng shui thing, where your external chaos reflects your internal chaos, etc., so the tidying, I think, is crucial to my mental and creative functions.

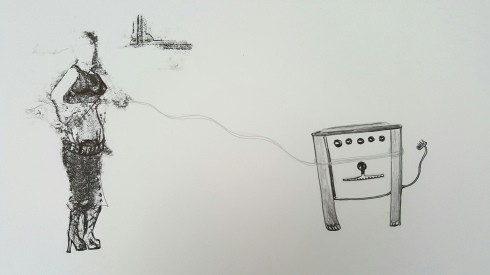

‘HouseCritter Domesticated,” transfer and flashe on paper, 14 x 17

‘HouseCritter Domesticated,” transfer and flashe on paper, 14 x 17

But when I start teaching full time again, three classes a semester, my days fill up. I have to be places other than my house. I am mentally and physically drained from trying to get the twenty-six students in my Introduction to Diverse Literature class to care about the colonial reverberation of Wordsworth in Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy. No more productive procrastination. No more “exercise.” I’m barely keeping up with the basics: dishes, litter boxes, garbage, in addition to tending to the occasional leaks and appliance malfunctions. Toilets are not getting cleaned. Floors are not swept. My feng shui haven is crumbling around me.

Then, I make a discovery. My beloved’s office, a spacious upstairs room with French doors, great light, and an enviable secret study nook, is filthy. Enormous tufts of dust and hair. Beer bottles. Dirty dishes. My beloved’s office is actually a “man cave” – even if it is filled with books about Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley.

What was going on? Where was the man whose bed was always made when I slept over? The man who had stockpiled an impressive array of cleaning products during our courting months? I mean, he had a Swiffer before Swiffers were cool. This was the person who had taken me to my first Ani DiFranco concert. The person who won an award for an essay about a woman writer for a journal dedicated to American women writers. This person…did not clean the house. Was not even thinking about it. He was behaving like – a stereotypical man? And I was turning into…gulp…my mother.

I staged mini-strikes in private, in my head, as the bathroom sink gathered hair and toothpaste dribble. He didn’t notice. I doubled down on before- and after-work cleaning, thinking it really was me, that I was weak. I mean, I didn’t even have kids. I should be able to just rally and do it all. But, but…it felt…unfair. And it was not just the lack of doing the tasks, it was that it seemed not to even occur to him. I resented the fact that his mind was free from the worry or concern of housework.

A few internet searches and I realize that I am not alone. A variety of recent studies, think-pieces, and articles reveal that, while men have increased participation in childrearing and cooking, their housecleaning lags way behind. Some speculate that, while childcare and cooking can be fun or rewarding, cleaning is not, and men lack the motivation to do it. Advertisements for cleaning products are rarely aimed at men, so there is no commercial imaginary in which men can place themselves with a mop and rubber gloves. Some reason that, if men innately value cleanliness less, women should lower their cleanliness threshold to reach a compromise. In other words, they should just chill out. [4]

I have trouble getting on board for this. Even if men value cleanliness less, that preference is always already gendered. For women, a clean, orderly house is the first defence against an avalanche of other gendered labor: response to illness, care work, attending a house in disrepair, managing social judgment of one’s status, femininity, and living conditions. I proudly acquired not just Virginia Woolf’s “room of one’s own,” but an entire house, at age thirty. This house assures my independence, my autonomy, a space of refuge from patriarchy. It is the very conditions of my freedom of thought. It does not have to be spotless, but I value it too much to neglect it. Even when sharing it, I don’t buy that the resistance to cleaning is truly about preferring a messy house. It’s just valuing not cleaning more. However, claiming not to care, which my partner often does, dismantles the logic of the housework strike. There’s no leverage if the other person can wait you out indefinitely, or at least longer than you can stand the accumulation of grime and mess.

“HouseCritter in its Habitat,” transfer and acrylic on paper, 14 x 17

“HouseCritter in its Habitat,” transfer and acrylic on paper, 14 x 17

Even in heterosexual households where both parties perceive themselves as valuing gender equality, there remains massively unequal distributions of household tasks along stereotypical gender lines. What is fascinating is how these individuals who “ascribe to an ideology of equality” justify, rather than confront, such gender-constructed roles. A study of twelve professional households in England found that both men and women explained this division based on some combination of the following: 1) competence, or “female chauvinism”: i.e. women are just better at cleaning than men therefore they should do it; 2) satisfaction: women take pride and a sense of accomplishment in housework: i.e. they want to do it; 3) workload: men’s jobs are perceived as more stressful and demanding: i.e men have less time and energy to do housework, even when both parties work full time, and women simply must do it; and 4) division of duties between housework and food preparation, with men being quite willing to pursue complicated recipes while women do the cleaning. (Ding ding ding! There we were! My beloved’s cooking turns out not to be as revolutionary as I thought…) [5]

This analysis demonstrates that many of these excuses reinforce the workplace as a “male” space, and men’s professional lives as more important than women’s – a perception further supported by the persistent wage gap between men and women. Such excuses also reinforce gender essentialism, and the study concludes that even those couples most likely to be influenced by discourses of gender equality are still rarely able to achieve such equality in their own homes. This, decades after my mom’s housework strike. We were among them. I was as complicit as he.

Good feminist that he is, my partner was never defensive when I pointed out other manifestations of his male privilege. Things like writing holiday cards, for example, a form of social and affective labor which I felt obligated to do (and which he could take or leave.) I argued that his more relaxed attitude toward both keeping track of his finances and having a grasp on driving directions were a function of male privilege. The vigilance I applied to my finances and whereabouts were necessary for my independence and safety, respectively. In certain ways, calling these out as gendered depersonalized and de-escalated conflict. But when I reached the point of realizing that two adults lived here, two people who could be both thinking of and performing housework, I hit an impasse: how to bring it up? How, in effect, to ask for help for something that should have been a shared responsibility in the first place?

Our first passes at this did not go well. I began to point out that he had never, ever vacuumed the stairs. I asserted this as ontological difference. Could he possibly see the world from my position as someone who vacuumed the stairs? But if the stairs served as the example par excellence, my needs soon became much more practical. I desperately wanted him to take the initiative and do the dishes (even if he cooked). To tidy. To maintain. To take up mental awareness of the needs of the house.

The first time I asked him to clean the upstairs bathroom, his entire physical demeanor changed. Nervous, I chose my words carefully and kindly – or so I thought. His tone became sarcastic. I pushed. He asked when I wanted it done. I said this weekend. He waited until 11pm Sunday evening to start. Now I didn’t feel like my mom, I felt like his mom.

I stewed during this weekend-long showdown. Why was he making this so difficult? Why did he seem to recoil upon my request? Why didn’t he want to clean the bathroom, and do it immediately and well? The right way to bring it up, to ask, became like the riddle of the sphinx. Some perfect combination of tone, syntax and timing would unlock his eager willingness to pitch in, without starting a power struggle.

This impasse really stumped me. We are generally very good communicators and listeners. How had the issue of housecleaning undone our smug, enlightened exchanges? I desperately wanted him to capitulate, to say, “Yes. My unwillingness to clean, indeed, my complete obliviousness to it, is the result of patriarchal culture, just as is our unconscious assumption of these duties. Together, we must forge a new, equal partnership.” That was not happening. He grew tense, and I felt forced to nag, to play the martyr, to beg. This was getting ugly.

It was then I recalled a bit of wisdom from my best friend: calling out tension before it gets out of control. She and her husband use a phrase “fight coming on” to verbalize growing tension and miscommunication. A short sentence to bring them together through shared, simple vocabulary. It’s like the efficiency of my mom saying she’s on strike, but less divisive. The right word for the right occasion. But this time with levity. Humor. Truth. Could some version of this help us?

After much frustration and fine-tuning, we have arrived at language to describe the tension of the housework negotiation. This language does not erase the experience which it describes. Instead, it brings it to the foreground. Being able to name these things makes me feel more empowered, while owning his experience lets my partner arrive at cleaning on his own terms. The magic words are:

“Seizing up.” This is the phrase we use to describe my beloved’s reaction when I ask him to do the dishes, take out the garbage, change the sheets, etc. He experiences a visceral reaction including muscle tension, shortness of breath, possible organ failure, and irrational rage. Before we codified it as therapeutic vocabulary, I would call him out on this (over)reaction to my requests, saying “it’s like you are seizing up!” And he said “that’s how it feels!” So now, we make good use of this language to honor his experience, acknowledge it. I’ll say, “Hey, can you bring that basket of laundry downstairs.” And he says, “I’m seizing up!” Its half joke, half reality. He owns his reaction: societal, gendered perhaps. I exercise more patience, accept that he will do housecleaning even if he does not want to do it and then we proceed to delegate and execute chores.

“Teenage ____ (insert proper name of beloved).” This is related to the phrase above. It’s the transformation my beloved undergoes when I ask him to help out. It includes seizing up (see above), but can also encompass pouting and insisting that he’s okay living in a filthy house, that cleanliness is not a requirement for him. He rarely self-identifies as his teenage self, it’s more me who says, “OMG you are turning into teenage “proper name.”

It’s at these times that housework requests feel both gendered and parental. I am sympathetic to this position because I myself, like most adult children, can still regress to “teenage Tara” (who is not as enlightened or eager as eleven year-old Tara of the diary entry) when my mother, now in her 70s and desperately trying to downsize, asks me to sort through the ancient drawer of concert tees in my childhood bedroom. Seriously, I have to decide if I want to keep my Depeche Mode Music for the Masses t-shirt right now? There is always a sense of urgency in her requests, and a sense of imposition. I resist. Is my resistance a resistance to the task itself? No, it’s a mini power play, a micro-war, started by me. The request is posed as a question, but implied as a demand. Aren’t you just trying to lure me into the web of housework misery?

“All Beasts,” Acrylic and transfer on wood panel, 6×6

“All Beasts,” Acrylic and transfer on wood panel, 6×6

No. I realize the answer now: definitively, no. My mom just wants the drawer cleaned out. She has probably wanted it cleaned out for twenty years. What feels like the capricious wielding of power at me is actually the frustration of powerlessness, the asymmetrical gesture of asking for help for tasks that should be shared. “Why does it have to be done now?” Because, most women have been waiting years for someone to do that very thing WITHOUT THEM HAVING TO ASK.

The Housework Awards: When my beloved does do housework of his own volition (which happens slightly more often now) we joke that the awards ceremony will be at 7pm, so he should begin preparing his thank you remarks.

I still end up in the nagging – sometimes verging on begging – position when it comes to house cleaning: a lifer feminist impatiently waiting for her partner to initiate vacuuming the stairs, seeing this as the most important feminist battle frontier of my life. His mental and emotional connection with the house is entirely different than mine. I never thought the housework situation would break us, but it did challenge the idealization I had made of our partnership. Having just finished a semester teaching Women’s Writing, talking through Woolf, Cixous, to Rankine and Adiche, I understood even more deeply my privileges as a white straight middle class cisgender American woman – but I still felt patriarchy wedged right in the kitchen of our house, threatening our intimacy and trust. It made me aware of a particular quality of all forms of privilege: the privilege to not think about something. And in not thinking about this one thing, one has room for other things: self-reflection, ambition, empathy, daydreams about sports, food, sex, etc. As recently as a few months ago, he didn’t know where the recycling bags are kept. I envied that free space in his mind that up until I told him, was not occupied by knowing where the recycling bags were.

Works Cited

[1] This report, issued in Nairobi, was part of the culmination of the U.N. Decade on Women. The subsequent World Conference on Women (Beijing, 1995) continued to push for policy attuned to women’s labor, while also seeing unpaid labor as a specifically feminist issue. In the years since, approaches and methodologies have been continually debated as to determine how to attribute value to housework; if attributing value has a feminist impact; and if and how housework should be included in GNP, etc. See Swiebel, Joke. “Unpaid Work and Policy Making: Towards a Broader Perspective of Work and Employment.” UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. DESA Discussion Paper Series. February 1999 http://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/1999/esa99dp4.pdf

[2] Kendrix, Kathleen. “Women Want Credit Where Credit Is Due : ‘Time Off’ Rally Seeks International Recognition for Paid, Unpaid Work.” Los Angeles Times. October 23, 1985. http://articles.latimes.com/1985-10-23/news/vw-14061_1_unpaid-work

[3] Brewer, Kirsite. “The day Iceland’s women went on strike. BBC News. Magazine. 23, October 2015. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-34602822. Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, the first democratically elected female president in the world, attributes her ambition to run for office to that day, where she stood in Reykjavik Square with both her own mother and three year-old daughter.

[4] For more on these various speculations, see: Lindsay, “Wife Strike.” http://feministing.com/2012/08/23/wife-strike/; Valenti, Jessica “The Daddy Wars” The Nation. June 27, 2012. http://www.thenation.com/article/daddy-wars /; Grose, Jessica. “Cleaning: The Final Feminist Frontier” New Republic. March 19 2013 https://newrepublic.com/article/112693/112693; Bradner, Alexandra. “Some Theories on Why Men Don’t Do as Many Household Tasks” The Atlantic. March 11 2013. http://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/2013/03/some-theories-on-why-men-dont-do-as-many-household-tasks/273834/?single_page=true; Chat, Jonathan. A Really Easy Answer to the Feminist Housework The Daily Problem Intelligencer March 21, 2013 New York Magazine http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2013/03/really-easy-answer-to-the-housework-problem.html

[5] Van Hoof explains her specific focus on heterosexual couples as follows: “While lesbians and gay men have had no choice but to employ creativity in negotiating their relationships without traditional roles to fall back on (Giddens 1992, Blasius 1994, Plummer 1995, Weeks et al. 2001, Heaphy and Yip 2003), heterosexual couples have had to attempt to move beyond traditional roles in order to embrace the late modern possibilities of equality and satisfaction (Giddens 1992, Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 1995). By focusing exclusively on couples living in heterosexual relationships my aim is to problematise heterosexuality” (20). Van Hoof, Jenny H. “Rationalising inequality: heterosexual couples’ explanations and justifications for the division of housework along traditional gendered lines.” Journal of Gender Studies Vol. 20, No. 1, March 2011, 19-30.

Writer Bio:

Tara Emelye Needham writes essays, poems, and pop songs. Her poems have recently appeared in Belleville Park Pages and Barzakh, and the lyrics from her current musical project, The Chandler Estate, appear in the Spring 2016 issue of Apogee Magazine. Tara teaches and researches in the areas of world literature, postcolonial studies, and feminist theory. In the 1990s, she edited the zine Cupsize (with Sasha Cagen), excerpts from which have been reprinted in The Riot Grrrl Collection (Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2013). Tara thanks her beloved for “cleaning up” this essay over the course of several drafts and edits. Tara can be contacted at taraemelye@gmail.com.

Artist Statement:

My “House Critters” portray kitchen appliances, cleaning supplies, and other every-day household items as little monsters. Cleaning feels to me as an exhausting and repetitive act that leads nowhere since it all becomes dirty again and the circle never ends. Besides that, the fact that Housework is understood as a woman’s task never agreed with my way of thinking. Coming from a household where tasks and household chores were equally distributed between my brother and I, it never occurred to me that women could be treated in a different way, or that there were specific tasks designated exclusively for one of the genders. I grew up oblivious of the term feminism, even though I was raised following every single statement and beliefs that it praises.

I come from a city -and a country, that was alienated, stereotyped and rejected by the rest of the world, so

I still do not feel comfortable labeling myself under any “isms”.

So much truth here! Thank you for articulating this dynamic so clearly, and for offering practical solutions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really enjoyed what you could make out of simple feminine frustration. Well, not that simple it drove me to a therapist! Well done! Love, Mom

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article, it brings up some very interesting dynamics we all face and solutions for actually facing them. Are there prints available of any of the art? I’m obsessed with Medusa and I need a poster of “DOMESTICATED MEDUSA” for my life to be complete…

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’re glad you liked it. You can request more information from the artist at her website: http://www.sandramackvalencia.com/

LikeLike

I can’t believe how accurate this is, so glad there are others out there. Can we make a club or something? And the “I’m seizing up” way of framing that moment is perfect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was a great read Tara. This sparked quite the conversation in my home. We have since decided to start using a chore chart to spread the love of the household chore. Speaking from personal experience, I have found a lot of what you are saying here to be very true. I have been with my husband now for 6 years and have found the dynamic to be very interesting around the subject of house cleaning. I have found I tend to be the one who breaks down more when it comes to this subject after what feels like a high noon pistols at the ready stare down to see who will budge and just make sure a cup goes into the sink. Your article opened up some communication we had not had in a long time. It was funny to note that both of our inner monologues on the subject were not far off from your article even though we are both men.

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks dan for sharing your experience with me and other readers! I love the image of “high noon pistols!”

LikeLike

I appreciate your thinking and thanks a lot to change my mind from this article…

LikeLike

Really interesting blog and I enjoyed your blog very much…Keep it up

LikeLike