By Andreas Petrossiants

– Mary N. Taylor and Noah Brehmer (eds.), The Commonist Horizon: Futures Beyond Capitalist Urbanization (Common Notions, 2023).

– Noah Brehmer with Vaida Stepanovaite (eds.), Paths to Autonomy (Minor Compositions and Lost Property Press, 2022).

It is a peculiarity of Western art that autonomy should be thought of and philosophically grounded in opposition to economic autonomy. —Katja Praznik, 2022

The future commons boils down to two elements: access to land (i.e., food and fuels); and access to knowledge (i.e., capacity to use and improve all means of production, material or immaterial). It’s all about potatoes and computers. —Midnight Notes Collective, 2009

In the 1990s, the Midnight Notes Collective (MNC) reminded a recomposed global left that just because the Marxist tradition had so thoroughly summarized the “primitive” enclosures that allowed capitalism to develop, did not mean that those tendencies were “one times process[es] exhausted at the dawn of capitalism.”[1] Inspired by the cosmological and tactical theory produced by and for the Zapatistas’ construction of an autonomous community on land re-commoned from the Mexican state, MNC argued further: “Any leap in proletarian power demands a dynamic capitalist response: both the expanded appropriation of new resources and new labor power and the exhaustion of capitalist relations, or else capitalism is threatened with extinction.” In other words, enclosures gonna enclose, and practices of commoning back what was taken are central to building popular and collective autonomy to contest capitalist recuperation.

Building from two decades of internationalist, feminist, and anti-colonial struggle, this conception was firmly rooted in an attempt to contest new enclosures dominating the so-called end of history—NAFTA, global marketplaces, European monetary integration, neoliberal colonial extraction—and for bringing together different scales of exploitation and resistance: from the socially reproductive work of the individual care-giver to proletarianizing workers in cities across the Global East and Global South who were rapidly inserted into Western capitalist markets and wage-forms.

This discourse was also indebted to Autonomia, a heterogenous and heterodox movement in Europe in the 1970s, particularly in Italy during the “years of lead,” when a variegated left landscape included pirate radio stations, occupied social centers, ultra-left Marxist organizations, and armed insurrectionary contingents. Indeed, many of the members of MNC participated in movements for autonomy, especially feminist critiques of unwaged domestic labor through the Wages for Housework Campaign and its internationalist coalitions. It is for this reason that the editors of a new volume, The Commonist Horizon (CH) assert that the idea of the commons works to break apart the distinctions between production and socially reproductive labor. For Anthony Iles, in his contribution to CH, another key reference is “the long tradition of ‘history from below,’ its concentration and politicization by the postwar New Left (E.P. Thompson, Dorothy Thompson, A. L. Morton, Christopher Hill, Raphael Samuel, and many others), and the connections between their studies of historical enclosure in the UK and the activities of the peace movements in the 1950s through the late 1980s.” (42)

CH and another edited volume, Paths to Autonomy (PTA), are recent anthologies that emerge from related networks of locally based but internationally geared projects for autonomy and commoning. For PTA, Noah Brehmer and Vaida Stepanovaite invited numerous comrades and theorists to participate in workshops at an autonomous social center in Vilnius, Lithuania. Essays and interventions that followed from these conversations probe questions related to organizing in the art world, the recuperation of social and aesthetic movements by neoliberal cultural institutions, the pitfalls of traditional trade union organizing in precarized and casualized sectors, and much else. In CH, related topics are approached from the perspective of cities, urban planning, and forms of commoning that strike against the material expressions of property and capitalist land use. They cover cooperative housing projects in Belgrade and Hungary, artistic interventions and recuperated forms of the same in London, as well as remarks on collectivizing care in New York City following the Covid Pandemic by the Carenotes Collective. All the above is framed through or in debate with commoning, which is defined by Stavros Stavrides in the preface as “encompass[ing] the practices that move in the opposite direction of what several authors in this edited collection refer to as capital’s spatial fix, to reclaim what should be shared as common as well as to produce more areas of sharing.” (ii)

Reading the books together presents an opportunity to think about how struggles for building autonomy and for “reclaiming” the commons are at times related and at others in conflict; in other words, by reading the texts side by side we can think these questions dialectically. For Noah Brehmer and Mary Taylor, “The commons, or commoning, in the tradition from which we write, is a revolutionary proposal for the communal organization and control of the manifold realities that make up our daily reproduction. … From cooperative housing to district kitchens, autonomous health clinics and community gardens, then scaling up to solidarity economies, we approach commoning as a horizon for reimagining and transforming social life against and beyond capitalist urbanization and accumulation.” (1) In PTA, on the other hand, Brehmer defines autonomy through one of its key formulations theorized by Operaismo: the “refusal of work,” which as Stevphen Shukaitis writes in his contribution to that volume, “plays a key role in fermenting class struggle as it provides a framework for moving from discontent to action, underpinned by a concrete utopian desire to reduce and if possible eliminate the influence of work over social life.” (66)

As made clear in the title of CH, the editors are framing their research in opposition to Jodi Dean’s more orthodox conception of communist organization, lampooning her 2012 The Communist Horizon. As the editors describe, however, the connections between the commons and communism are more nuanced than pure opposition. Furthermore, “If commoning is emphatically not Communism (as any form of existing state socialism) its relationship with many historical and contemporary communisms is worth exploring.” (4) The first text in the volume, Ana Vilenica’s “Who Has ‘The Right to Common’? Decolonizing Commoning in East Europe,” approaches these questions by problematizing the active forgetting of Soviet-era commoning experiments in contemporary left discourse in Serbia. For Vilenica, the “systematic disregard of these histories, and others that have followed in contemporary Serbia, point to the neocolonial ‘Western activist outlook’ imposed by middle-class civil society organizations during the transition to capitalism and alleged ‘democratization’ in Eastern Europe after the Yugoslav socialist experiment ended.” (12) Vilenica points to those histories to ask, “How do we build a left decolonial approach from the East when the right loudly articulates an anticolonial position?” (13) Looking at several groups that were active in Belgrade in the 1970s and 80s, her research demonstrates numerous cooperative housing projects as well as novel forms of organization between workers in the cities and in the countryside. She also underlines the centrality of racism (against Romani populations) and endemic misogyny that was at the root of ostensibly liberatory Yugoslavian housing policies that continues under contemporary capitalism. Soviet-era laws may have granted a much larger percentage of workers access to stable housing than countries in the West, but women were still subject to entrapment in abusive relationships to secure housing while Romani people were actively displaced from much housing. She concludes in the present day, in Belgrade, where 87 percent of residents own their homes. Notwithstanding this figure, neoliberal urban planning, which caters to foreign capital and prioritizes the construction of luxury housing, reigns just as in the West.

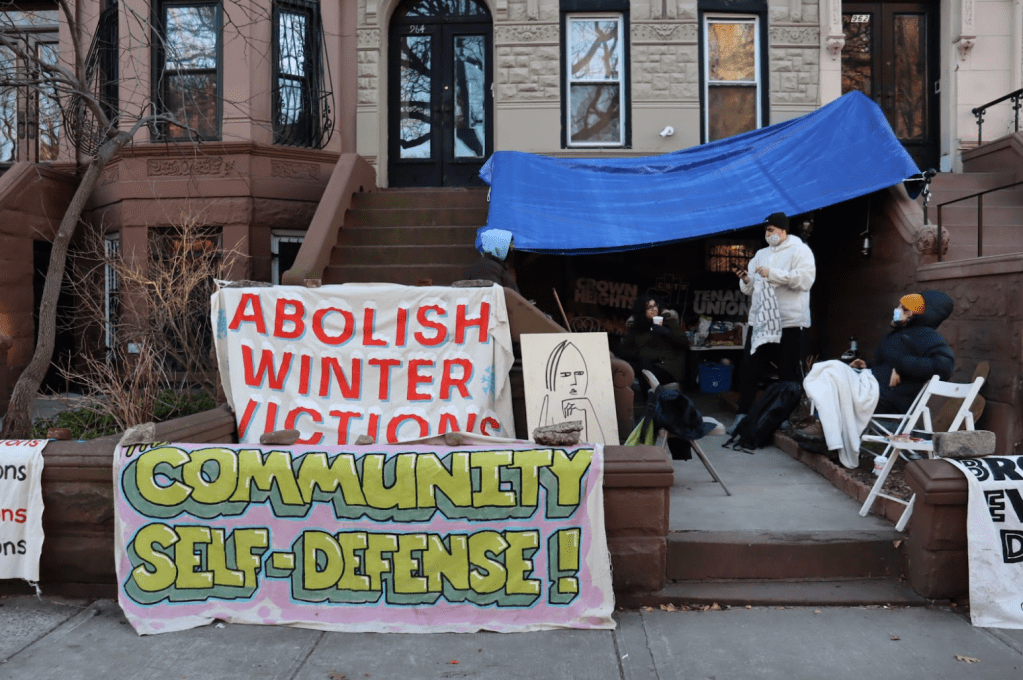

In this way, we can see the generalizability of neoliberal approaches to land use and municipal planning if we compare Belgrade to a city like New York where only 33 percent of residents own their homes. Acknowledging that vastly different contexts experience similar forms of planning thus allows for the creation of solidarity networks, like those expressed in the publication of both books, that transcend geographic boundaries. Consequently, fighting for the commons in Belgrade or New York may not look the same, but can work in concert. Highlighting contemporary organizations fighting for housing justice, Vilenica finds an expression of the commons. “Tenants, their allies and accomplices, as well as material infrastructures,” she writes, “are among the potential actors in housing commoning. Housing commoning is more than a temporary fix intended to fill gaps left by an inefficient welfare system. It also includes militant political acts that show the failure of the system to deal with the permanent housing crisis.” (33) We can compare this to groups in New York City like Brooklyn Eviction Defense who are constructing an autonomous tenants’ union through the tactic of actively resisting evictions throughout the borough as well as a newly formed revolutionary reading group.

It is because of this potential for transnational solidarity through the prism of the city that the editors of CH center urbanism. Describing this choice, they write that firstly “capital accumulation is closely tied to urbanization, to transformation of the built and natural environment in manners that are tied to tricks of finance and hasten the frequency of the crises we are experiencing.” (6) Secondly, more than half the world’s population lives in cities, and the last two decades have seen countless expressions of urban rage erupt after mass transitions of workers from the countryside to urban centers; the Arab Spring and recent struggles by oil-sector workers in Iran are recent examples. But, as Murray Bookchin stressed in his 1974 Limits of the City, conceptions that reify the Marxian “anthesis” between the town and countryside will ultimately fail to see the potential to blend the two “into an artistic unity that would open a new vision of the human and natural experience.”[2] Indeed, it was Operaismo’s novel approaches to the so-called “Southern Question” (in Gramscian terms) which allowed theorists of the 60s to see the division between town and country as illusory forms of reinforcing the postwar division of labor—a fiction enforced even more strenuously by the Communist and Socialist parties whose orthodoxy prioritized developing liberal capitalism and a Peninsula-wide industrial proletariat. For these and other reasons, the editors affirm that they begin from cities because they begin with their own experiences, but that “cities are not independent of the countryside. Rather, they are dependent in so many ways.” (5)

Furthermore, by thinking through the city, as already alluded to in the examples of Belgrade and New York, the question of scale becomes pronounced. Both books invite questions about how to avoid the problem of losing connection to local contexts and struggles as coalitions grow. As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney have put it elsewhere: “scaling up is really scaling down, losing connection rather than gaining it, losing abilities rather than consolidating them, settling for form rather than formation.”[3] In a recent conversation between Mary Taylor and Janet Sarbanes about CH, Taylor underlines the importance of this question which is explored in the book through sites that made the transition from state communism to neoliberal capitalism: “Much of what is called commoning is pursued on very small scales and it is often involved in reproducing very small, sometimes even privileged, groups. … If self-governance is what we are interested in, how can islands of commons and commoners find ways to cooperate so that they have a chance of survival, or even become significant in the context of the scale of the capitalist organization of the economy and our everyday lives?”[4] In a conversation between Mary N. Taylor, Zsuzsanna Pósfai, and Ágnes Gagyi, in CH, the latter two (housing organizers in Budapest) critique the notion of the commons, opting instead for what they refer to as the solidarity economy. While the former, in Ágnes’s conception is about property structure, the latter is “a movement to transform everything … a technology to disrupt and transform all the means of value circulation.” (89–90)

This resonates with Marina Vishmidt’s intervention in PTA, “Unionism, Diversity of Tactics, Ceaseless Struggle: Dispatches from Cultural Workers,” where she discusses her previously defined concept of an “infrastructural critique.”[5] Similar to how Pósfai and Gagyi see property and its distribution as a roadblock to commoning practices under existing capitalism, for Vishmidt, an infrastructural critique directly intervenes at sites of distribution and production. Rather than performatively critiquing (cultural) institutions for their involvement in regimes of extraction, violence, and militarization, Vishmidt stresses the importance of mapping the webs of connection between different institutions and of repurposing those infrastructural vectors

Indeed, today, the role of art and aesthetic practice in the development and ideological reproduction of the neoliberal city, a further enclosure of cultural practices, invites analysis of how artists have participated in commoning and how those approaches have been co-opted. In PTA, Katja Praznik’s essay looks at how the shift to capitalism in post-Soviet Yugoslavia demonstrates the centrality of “creative” or “cultural” labor to the construction of the neoliberal paradigm of work: autonomous, flexible, casualized, and “free.” For Praznik, by looking at the Yugoslavian case, we can see that under existing Socialism, artists were often casualized under similar rubrics. “Cultural workers and artists,” she writes, “were turned into a sort of experimental vanguard for the neoliberal reforms that began in the 1970s,” where “an implementation of market principles in the field of culture … began to redefine art workers as socialist entrepreneurs.” (48–50) Describing the fall of Yugoslav socialism, she concludes: “In the 1980s socialist cultural policy reinforced the valence of creativity and exceptionality of art work. Artistic exceptionality or if you will, creativity, became the foundation for basic social rights. Independent art workers had the right to social protection not because they were working but because they were exceptionally creative.” (51)

In CH, Anthony Iles’s text looks at art’s imbrication in contemporary modes of neoliberal governance as made explicit in gentrification and marketization schemes in London. He brings up the centrality of financialization as an urban strategy, (44) and discusses the use of art to power gentrification under the cultural policy of the new labor government in the late 90s. (46–47) “While widely criticized, the creative city model has far from completely collapsed,” he writes. “However, practical and theoretical opposition to it has become a substantial force, and … in this process art has been made both the alibi and internal antagonist of urban redevelopment projects. Art has also become a key placeholder for the commons, and discourses of the commons have increasingly been taken up within the arts as well as in activism globally.” (40) Referring to New York City once more, we can compare Iles’s account with how artist and organizer Shellyne Rodriguez recounted the connections between artists, non-profits, police and other city agencies, and real estate developers in the Port Morris and Mott Haven sections of the Bronx. However, for Rodriguez, “artists experience this crisis of the disappearance of space alongside other New Yorkers in many ways. … Rather than only thinking about the aesthetic qualities of space, artists can aim to topple the neoliberal scaffold that holds capitalism steady above us, like a firmament.”[6] This provocation resounds in Iles’s text as well where he concludes with a discussion of a text by the Situationist Peter Porcupine, which he ties back to the commons:

Rather than affirm use against exchange, Peter Porcupine’s prickly piece argues that “the left remains gripped by alternative resource management.” Instead of criticizing encroachment on human experience, the left aspires to manage, and this logic amounts to simply “arguing for public rather than private enclosure.” From this perspective, there is then a world of difference between the strategy of unenclosure and the establishment of socialism. Is there a path to full social reproduction which refuses a choice between small-is-beautiful gestures of impotence and “jet-set willy” left accelerationism? (61)

Another key notion to the construction of a world in common, and a prerequisite for autonomy is care. As Carenotes Collective write in their entry in CH, “[W]e believe that the sphere of social reproduction is central to the ways we can common ‘against and beyond capitalism.’ We thus begin with some thoughts on ‘care’ and ‘care work’ in terms of social repro- duction and the reproduction of collectivities.” (110) Describing their networks in New York City that connect community gardens that produce foods for biomedical and restorative care, coalitions of medical care-providers, and other collectively managed socially reproductive workers, they invite us to “Imagine endless lobbies and auditoriums for teach-ins and assemblies; rooftops and parking lots for refarming and horticultural therapy; and walls for murals and vertical gardens for our herbal remedies!” (116)

An example of a contemporary struggle in the US that is fighting for a commons and for autonomy from a militarized police force is the fight to Stop Cop City and to Defend the Atlanta Forest. Currently underway, it is expressed in a vast autonomous movement of organizers, artists, tree-sitters, and others have been defending a massive publicly used forest in Atlanta from complete deforestation and the development of a police training facility. Activists from across the Americas have participated in the struggle, in person during weeks of coordinated action as well as in their respective locales. The Ndn Bayou Food Forest in New Orleans, for example, who participated in the forest defense, have been actively introducing collective farming techniques in their neighborhoods, building a food commons.[7]

In his history of May Day, Peter Linebaugh, describes remarks that the proletarian holiday is both green and red: red for color of battle and class struggle, green for the earth. He remarks that this dual character is expressed in that it is a holiday during which people fight against the “dis-commoning” of the earth.[8] Reading the two books in question here, we see that commoning is a constant process between these two colors and others, a dynamic rather than stable reality that is actively imagined by people working together. It is a material conception, but also raises questions about scale, organization, collaboration, accountability, and much else. “As the indigenous Americans put it, in order to collectively eat from a dish with one spoon, we must decide on who gets the spoon and when,” Midnight Notes write.[9] “This is so with every commons, for a commons without a consciously constituted community is unthinkable.”

[1] Midnight Notes Collective, “Introduction to the New Enclosures,” Midnight Notes no. 10 (Fall 1990), available here: https://libcom.org/article/midnight-notes-10-1990-new-enclosures.

[2] Murray Bookchin, The Limits of The City (Black Rose Books, 1986), 3. Here Bookchin uses “Marx against Marxism,” in much the same way that some of the central theorists of Operaismo proposed, to deal “with the city as more than an arena for class antagonisms.” (6)

[3] Fred Moten, Stefano Harney, Sandra Ruiz, and Hypatia Vourloumis, “Resonances: A Conversation on Formless Formations,” e-flux journal, no. 121 (October 2021), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/121/423318/resonances-a-conversation-on-formless-formation/.

[4] Mary N. Taylor and Janet Sarbanes, “From Islands of Commons to Collective Autonomy,” e-flux journal, no. 136 (forthcoming, May 2023), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/136/537317/?preview.

[5] See Marina Vishmidt and Andreas Petrossiants, “Spaces of Speculation: Movement Politics in the Infrastructure,” Historical Materialism, blog, November 2020, https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/interviews/spaces-speculation-movement-politics-infrastructure.

[6] Shellyne Rodriguez, “How the Bronx Was Branded,” The New Inquiry, December 12, 2018, https://thenewinquiry.com/how-the-bronx-was-branded/.

[7] Autonomous Farming Collectives, “Planting and Becoming,” e-flux journal, no. 128 (June 2022), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/128/472900/planting-and-becoming/.

[8] Peter Linebaugh, The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day (PM Press, 2016).

[9] Midnight Notes Collective and friends, “Promissory Notes: From Crisis to Commons,” (2009), available here: http://www.midnightnotes.org/Promissory%20Notes.pdf.

Author bio: Andreas Petrossiants’s writing has appeared in The New Inquiry, Artforum, Bookforum, Frieze, The Brooklyn Rail, the Verso and Historical Materialism blogs, and e-flux journal, where he is the associate editor. He plays soccer with Stop Cop City United in New York.