Jess Flarity

**CONTAINS SPOILERS for all the Mad Max films**

Like many Mad Max fans, I watched Road Warrior (1981) countless times on my family’s home VHS player as a teenage boy in the late 1990’s. Along with the other action-sf films in our bootlegged collection (often copied after renting them at the movie store) such as The Running Man (1987) and The Terminator (1984), I found these gritty depictions of the future preferable to hokier space romps, such as Star Wars and Star Trek. Considering these types of movies are usually less lucrative than mainstream sci-fi, the box office failure of Furiosa (2024) has left me concerned. Was the shortage due to moviegoer’s tightening budgets? Had too much time passed since the 2015 release of Fury Road? Was it due to the success of the Fallout tv series (2024), whose similar release date possibly burned out viewer’s tastebuds for anything with a post-apocalyptic flavor? Or was it because Charlize Theron, the original Furiosa, was replaced with Anna Taylor-Joy, confusing audiences with both an actor swap and the lack of the titular character, Mad Max?

Rather than speculate on why Hollywood may or may not be in a death spiral, this essay will discuss feminism’s relationship to capitalism via the Mad Max movies, focusing specifically on similarities that occur in both the “sequels,” Beyond Thunderdome (1985) and Furiosa (2024), in contrast to their counterparts, The Road Warrior (1981) and Fury Road (2015). I will argue that the sequels are more aligned to fantasy than action-oriented science fiction, due to their focus on worldbuilding rather than chase and fight sequences. This genre switch, most importantly for Blind Field, creates potential for Beyond Thunderdome and Furiosa to have a more nuanced approach to feminism, yet these films still fail to escape the stranglehold of patriarchal norms.

For reference, here’s a quick breakdown of the earning power of the entire series:

Mad Max: Budget $200,000, Box office, $99 million*

Road Warrior: Budget $4.5 million, Box office, $36 million

Beyond Thunderdome: Budget $10 million, Box office, $52 million

Fury Road: Budget $185 million, Box office, $380 million (filmed primarily in Namibia because excessive rain caused wildflowers to bloom in the Australian desert, see image.)

Furiosa: Budget $168 million, Box office, $172 million (the most expensive film in Australian history. Due to aggressive marketing, it is estimated that it needs $350 million to turn a profit.)

Tilting from Science Fiction into High Fantasy

The discussion of fantasy vs science fiction has a long and embittered history; Ursula K. Le Guin argues that the two overlap so closely that an exclusive definition is “useless” (The Language of the Night 21), but meaning emerges when we investigate the Mad Max sequels. The later movies are so much more fantastical than their earlier counterparts that the films are almost high fantasy (as in, Game of Thrones and Lord of the Rings) and wear science fiction as a kind of costume. This unspoken genre swap is ultimately what turns off (primarily male) viewers due to the films having slower pacing and requiring greater leaps in the audience’s imagination.

Here is a striking first example of the genre shift: bullets.

At a pivotal moment in Road Warrior, the antagonist Lord Humungus sees Max bearing down on him in a tanker truck, so he must use his last precious five bullets to try and stop him. This is a terrific way of “showing” the viewer the setting rather than “telling” because we have to make our own inferences; we conclude the technology required to make more bullets has been lost, which also explains why crossbows are a common weapon used by the other wastelanders. This kind of cognitive estrangement is very logical and satisfying for the viewer to figure out, giving them a dopamine reward the same as solving a puzzle, focusing on (masculine) problem-solving rather than (feminine) imaginative world building.

Contrast this to Furiosa: after a long fight sequence at the Bullet Farm, the antagonist Dementus falls, almost comically, into a giant pile of bullets, as if he were a warmongering Scrooge McDuck. This creates a stunning visual image that obeys the rule-of-cool rather than building on the science fictional aspects of the post-apocalypse. The viewer is not rewarded with inferences related to the Bullet Farm and how it operates in the delicate wasteland economy, it just looks awesome. The scene only creates confusion if thought about too deeply: if there are this many bullets being manufactured, why doesn’t every single war boy carry an uzi? Why would these warriors sacrifice themselves using explosive spears when everyone could be strapped with a semi-automatic rifle? The movie eschews realism in favor of overindulgent hyperbole, thus projecting it into fantasy that makes room for thematic development; the excess of bullets, but lack of survival necessities, such as food and water, extends the film’s commentary about the extreme imbalance of power in the wasteland’s social hierarchy.

Another example is in the films’ approach to villains and their vehicles, as evidenced by the pink-mohawked villain Wez in the original Road Warrior, who rides a mostly stock Kawasaki Z-1000. Contrast this to Dementus in Furiosa, who rides in a literal motorcycle chariot (which, surprisingly, is an actual Australian pastime, and also is a nod to the pseudo-Greek/Roman influences on the film). Whereas Wez is stripped down in both his vehicle and character, Dementus is overly elaborate to the point of ridiculousness. Some of these differences are due to the increased use of computer graphics (CG) in the later movies, along with their noticeably higher budgets, resulting in impeccable details in costumes, settings, weapons, etc., while in the earlier movies it was more of a “put a few spikes on some football gear and call it good” approach. But in terms of dialogue and screen time, Dementus gets layers of backstory and long sequences of soliloquizing; in comparison, Wez is reduced to something almost like an animal (especially after his queer lover is killed, conflating his villainy with homosexuality), while similarly, Lord Humungus remains a mystery to the audience.

These are but two examples where the rift between science fiction and fantasy is clear; the earlier films have a measure of plausibility (bullets are valuable, a motorcycle would be useful crossing rough terrain in the desert), while the latter are fantastical (bullets appear like magic, a triple-bike chariot couldn’t even go up a slight incline without breaking).

These surface-level genre differences go deeper, however, when we look even closer at the main villains. In the first films, Lord Humungus and Immortan Joe are single-beat bad guys with one motivation: gas and women. The latter films have much more complexity, as Aunty Entity has a tenuous grip on Bartertown in Beyond Thunderdome and Dementus struggles to keep his biker horde in line throughout Furiosa. Due to their leadership roles, both these characters are layered with many more gray areas, ruling their societies through tyranny galvanized by personal tragedy. Both villains also identify with the protagonist by the end of the film, as Aunty Entity states, “Ain’t we a pair, Raggedy Man?” Similarly, Dementus, after being tortured in a variety of imaginary ways by Furiosa to complete her revenge arc, calls her a “fabulous thing” as a way of drawing attention to her own downward spiral into violent sociopathy, placing the two of them on the same moral level. These character nuances leave both sequels more room for feminist interpretations—but the films don’t take advantage of this, and instead transform the female characters into emotionless automatons to fulfill the expectations of the audience: in the wasteland, you must be absolutely ruthless regardless of your gender identity.

Side note: Aunty Entity’s ridiculous“chainmail bikini” outfit obviously belongs much more to fantasy than science fiction. This was filmed in the middle of the 1980’s, however…

Less Action Means More Room for Feminism…Possibly?

The trade-off between world and character building translates to less action and fight sequences in both of the sequels. I have not counted the films minute-by-minute, but I would guess that the sequels have about 50% less “exciting chase/fight” scenes than their predecessors, as well as a lot more dialogue. The worldbuilding of the earlier films is all in the subtext: an example of this is in the Road Warrior scene when we watch Max soaking up spilled guzzolene off the pavement with a rag and wringing it back into a dingy bowl; we make the inference that gas is valuable. Compare this to the pigshit factory of the Underworld in Beyond Thunderdome, which must be meticulously explained as to how the methane runs the electricity in the town; it is much more common in fantasy for the world to require an explanation, while science fiction can be understood solely through inferences. This same phenomenon occurs in the later films—Fury Road has a single streamlined scene early in the film where a war boy explains they’re going to “Gastown for more gas,” and the “Bullet Farm for more bullets”: that’s all we need to know as an audience. But in Furiosa, we get detailed ledgers about the economic exchanges between the three wasteland settlements, as if George Miller felt it was necessary for us to know the exact exchange rate of gallons of breast milk to gallons of diesel fuel…does this leave more room for feminism, or is he just making us do more heavy lifting as an audience?

There is also a fallacy in believing that fewer fight sequences might mean “more feminism,” as additional complexity or less violence doesn’t necessarily equate to gender equality. Once could argue that having Furiosa’s character arc end on her being a twisted torturer on the same level as Dementus is a refusal of gender essentialism. This complication of female characters is what Johanna Isaacson would call another “tool” for feminists; having Aunty Entity prove she can be a ruthless warlord shows that women can also rule with an iron fist just as capably as a man. But is this a good thing for feminism?

The answer to this question is centered around capitalism, as the action-sf blockbuster as a tradeable commodity or “art object” is inherently opposed to many principles related to feminism; this is why the recent attempts to create an explicitly “feminist action-sf film” have all failed: Birds of Prey (2020), The Marvels (2023) and Madame Web (2024) are just three examples that all tanked the box office (though these are also comic book examples). While there are powerful examples of feminist-sf succeeding commercially, such as Arrival (2016), Annihilation (2018), or Poor Things (2024), these are not action films, even if they are big-budget science fiction. The Mad Max films (at least, the latter four) all favor violent solutions to compromised negotiations, spectacle over substance, and mind-numbing sound and visuals over mind-expanding philosophical questions. The action film, especially Mad Max, is something that George Carlin would argue is detectable by its “combustible chemical formula: gasoline, gunpowder, alcohol, adrenaline…and that ever delightful accelerant, testosterone…”. As a medium, the action-sf blockbuster has to target the wallets of men still within the thrall of traditional manhood if it wants to succeed—“girl power” is still on the outskirts.

Thus, George Miller might believe that he is making art, that he is somehow advancing the sum of all human experience in his films, but we should doubt that Fury Road has transformed any of the men who dressed up as war boys for Halloween (witness me, “chroming” is an Australian term for inhalant abuse) away from their misogynistic worldviews. However, I have some male friends who point to the scene in Fury Road where Max allows Furiosa to use his shoulder to take the sniper shot as a perfect example of feminism—the most capable person is doing the job, no matter their gender—and so perhaps he has moved the cultural needle, at least a little, in the right direction (or at least, we can hope).

Complexity = Make Brain Hurt, No Watch Movie About Bad Revenge Lady

I think the main reason Furiosa spun out at the box office in comparison to Fury Road is obvious: it’s due to sexism of its primarily male audience (in contrast, Thunderdome and Road Warrior performed nearly the same, even if the latter was largely panned by reviewers, [not all of them, though, Roger Ebert was a fan]). No matter how many cool vehicles and visceral torture scenes this movie threw at the viewer, an expected 200 million dollars was kept firmly in the pockets of about 20 million people (mostly men) who have apparently refused to watch any movie with a female protagonist. This corresponds to the approximately 12 million people in the U.S. with alt-right leanings.

This failing point is very odd to me because Furiosa’s specificity as a woman is basically non-existent in this film—after she cleverly escapes the clutches of Immortan Joe as a child, she even passes for a mute boy for the entirety of her teenage years and she is allowed few complexities in her emotional life. This makes Furiosa—and really, the film as a whole— a bit of a conundrum for feminists. While Fury Road wears its feminism vividly on its sleeve, albeit with some complications, Furiosa is…well…not really doing anything that could be considered “consciousness raising” from a feminist perspective. Some reviewers are trying to dredge the film as being a critique on the dehumanizing aspects of the wasteland, but Dementus’ awkward monologue at the end just feels like George Miller is trying to justify why he put so many gory death and torture scenes in this film, even though he mostly uses the audience’s imagination against them, similar to the movie Se7en (1995).

In one extreme example, Furiosa’s mother is crucified and is presumably having her intestines/reproductive organs butchered while she is still alive, but she never breaks and tells her captors about the “green place”….so, that makes it *more* feminist? She also doesn’t kill a captive woman in the biker’s encampment when she rescues Furiosa, but then that woman immediately betrays her…so that makes it *more* feminist? Part of me is very doubtful about either of these claims—I’d argue that Miller is actually reinforcing dangerous sexist stereotypes related to women in both these instances, specifically the “woman as betrayer” cliche that goes back to the biblical Adam and Eve, as well as the “women are tougher than men” quackery that continues to plague the medical field related to women’s health issues.

Also, Furiosa, strangely, has less complexity as a character than Dementus, whose teddy bear he tells us belonged to his slain daughter (though this is never proven and could just be a lie). Every horrible thing that happens to Furiosa gets the audience to buy in to why she eventually becomes the “same” as Dementus, and the writer/director is obviously trying to pull the rug out from under us as we realize that she is also one of the “bad guys” by the film’s conclusion. But because this is a prequel and we know that she is ultimately redeemed by the previous film (in fact, we had this in the back of our minds the whole time), this punch from Miller just didn’t land for me. Personally, I left the theater having an estranged relationship with what the film was trying to say. Does a lack of natural resources make humans into animals? In our quest for vengeance, do we ultimately lose our humanity? The minute-plus Dementus soliloquy left a bad taste in my mouth, even if that was its intention.

Conclusion: Feminism Continues to Be Complicated and People Don’t Like That

Furiosa ends up being another unfortunate example of how incompatible feminism is with capitalism: even if something looks feminist, mainstream audiences will keep away from it. There’s also an interesting tug-of-war that might be going on behind the scenes between Miller and the people funding his very expensive movies—he earned them a ton of money with his first film, and that gave him the ability to have more creative control in the second film. This allowed him to delve more into what he loves as a writer (characters, worldbuilding, costumes, etc.), rather than what the audience wants (action, car chases, explosions). Although this allowed him to somewhat complicate the feminist messages in his films, it also led to audience rejection. This makes one wonder if the genre of action sci-fi can ever successfully convey a feminist message.

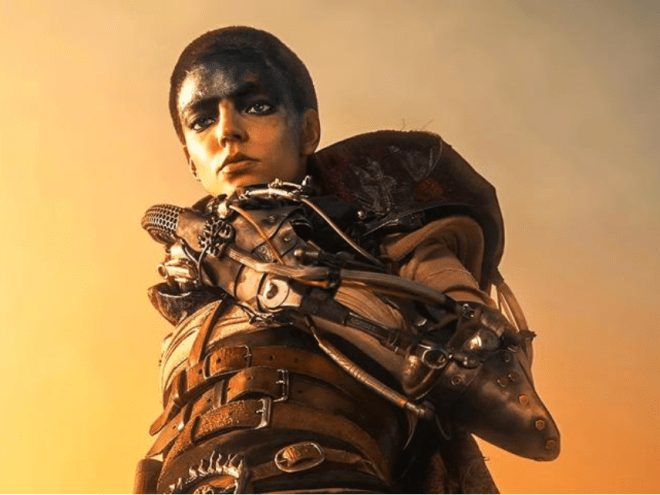

A final complaint from one of my dude friends, another Mad Max devotee, sums up a lot about how patriarchal hooks remain lodged into the minds of male fans. After the movie was over, he said to me, “Man, Anna Taylor-Joy was the wrong choice for Furiosa. Charlize Theron worked well for the first film because she’s a big, tough woman and I believe she could really beat me up. That chick didn’t have the right build to play the character…” Hmm, so despite everything else that happened in the movie, he remained fixated on the body of the actress playing the character rather than any of the actual plot events; for him, the cognitive estrangement buy-in into the Mad Max world could never be achieved because the fictional dream remained broken before it ever began, the waifish body of Anna Taylor-Joy unable to translate with his own ideas of a what a post-apocalyptic, badass woman should look like.

Feminism and Hollywood will continue to snipe at each other as the industry defragments into the countless streaming services chipping away at traditional movie theaters, and I see Furiosa as another casualty in this ongoing battle. Now that we all have cheap, 60+ inch TVs in our homes and can purchase new movies for only $20 (or steal them for free from pirate sites, the modern equivalent of VHS copying), the slow decline of the movie theater as a physical location seems inevitable. At the same time, Dune: Part Two (2024) seems to be doing just fine at a box office of $712 million, and Inside Out 2 has cleared over double that ($1.4 billion!) after only a few weeks…so perhaps Furiosa just didn’t quite click with people, like a misfiring cylinder in an engine. Similar to the Rick and Morty episode lampooning the tropes Mad Max helped create (Season 3, Episode 2), it appears that Miller could not transcend the genre he helped invent. That doesn’t make the film bad in itself…just a self-parody that feels unable to say anything new or useful for feminist theorists in the modern day.

P.S. I would like to point out how all of the Mad Max movies deconstruct notions of “abled vs disabled” in a meaningful way before ableism was even a neologism (which has roots in feminist theory, first appearing in Yvonne Duffy’s writing). There is already an entire book on this subject related to the series for those who are interested, and Furiosa continues in this tradition with the inclusion of Quaden Bayles after he was bullied at school due to his dwarfism. In this regard, I tip my hat to George Miller—more filmmakers should take notice concerning his approach, lest we keep getting films where actors like Hugh Grant get their own Oompa Loompa spin-offs.

Author bio: Jess Flarity has a PhD in English from the University of New Hampshire and an MFA from Stonecoast. He is currently an adjunct professor and publishes reviews and science fiction stories online.

Sources:

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Language of the Night. Perigee Books, 1979.

Suvin, Darko. Metamorphoses of Science Fiction. Yale University Press, 1979.

*All values in USD, not adjusted for inflation. Note that the original Mad Max (1979) was so successful that, despite its initial low budget, it held the world record for being the most profitable movie of all time until it was unseated by The Blair Witch Project (1999). Because this film is so different from the other four, it is outside the scope of discussion here.