Miranda Mellis

What is it that translates pricks of conscience into acts of conscience? What are the affordances that enable us to move from perceiving patterns of suffering to acting towards their alleviation? To alleviate, from the Latin levis, a la levitate, is to lighten a load, to share a burden, for example, so that it is easier to carry. Burden, etymologically related to birth, and brethren, implies the literal and figurative heaviness of reproductive labor, the bodily weight of kinship.

In Regarding the Pain of Others Susan Sontag thinks about the reception of images of suffering from afar, particularly the history of war photography. She writes that compassion in the face of such images is a kind of plant that dries up if not watered by action. If we are to go further than sentiment, than savoring and being reassured of our own goodness, she writes, action is the imperative. It is as if the difference we are speaking of when we speak of making a difference, is all in the verb making, as if there is no state of difference arrived at on the other side of making, but rather, the making is itself the difference. In that sense, action completes concern. To be concerned is only to begin to act. Concern alone is incomplete. It is not just incomplete: the implication of her essay is that it would be preferable to act in the absence of feeling, then to merely feel and fail to act. This is counterintuitive wherever there is a premium on sentiment. On the other hand, even for those inclined to act, regarding the pain of others far away we anguish that we aren’t proximal enough to make a difference that makes a difference. We can donate money, vote, send tents or medicine or books. It matters but feels abstract because we don’t feel in our bodies the alleviation of burden, as we do when we physically help carry the care.

In 2019 I volunteered at a family shelter where a handful of families who had no place to live, of which there were at the time some 3,000 in the county, could find temporary respite for some of the time, an abject kind of socialism. Here there was a shelf of books, a communal kitchen, pantry, linen closet, a washer and a dryer, a piano, a large open space, sleeping mats, a computer, doors that could be locked at night. At this shelter there were babies, very young children, teenagers, and their parents, usually just their mothers, many of whom worked long hours at arduous jobs. One of the things we volunteers did was hold babies whose parents were busy or absent.

I remember holding one baby whose body was stiff with tension. As a former childcare worker, I have held many babies in my life. But I had never held a baby with so much rigidity in his form, as if he felt himself to be a burden and was trying to hold himself, as it were, together, make himself lighter. His body was thinking, intelligently under the circumstances, “For lack of shelter, I will make a house out of myself by hardening my body.” He was trying to evolve an exoskeleton as we all do in the face of threat.

To hold a baby in a state of relaxed equilibrium is to feel tidal. There is a give and a sway, the baby like a water balloon, a rolling give and take, a sensing of that 70% of the body that is comprised of water. Your arms get tired. But holding this baby was like holding a ceramic jar, a hollow statue. My arms didn’t get tired because he held his weight back. He was tight muscle, bone and sinew. Keeping himself together, he had the frown of an old, disillusioned man reflecting the face of his prematurely aged teenage mother who was exhausted, frayed, angry, bitter, impatient, hardworking, and understandably short-tempered. This armored baby was truly the offspring of the arranged marriage between the state and techno-cartel capital.

A volunteer could temporarily, for a moment, very literally, slightly alleviate, make lighter, the birthed / burden of this young woman by holding her baby for her while she tried to elude the violence of the baby’s father and cope with a thousand problems trying to thread a path to futurity. The high stakes game was to somehow attain self-sufficiency in the face of byzantine, entrenched bureaucratic barriers and economic, legal, familial, educational, nutritional, architectural, and medical neglect and abandonment. In this sense the shelter, normatively viewed as a last resort, was in fact the only available solution, an assembly towards survival, a relic form of communism that is very much a product of American anti-communism, in which mutual aid and interdependency outside of the walls of the biological family are seen as evidence of failure and degradation.

Everyone is supposed to have been taken care of by their family of origin. The shelter system, and social services generally, are treated as symptoms of the failures of family, while in fact these are attempts to address the social pathology of irrational economism. The logic that social care should fall upon the family, while it is masked in sentimentality and religiosity, is in fact an aspect of irrational economism, with its pretenses to rationality, as if reproduction is just another iteration of “rational choice” by individuals in full command of the facts and in possession of sovereign liberties.

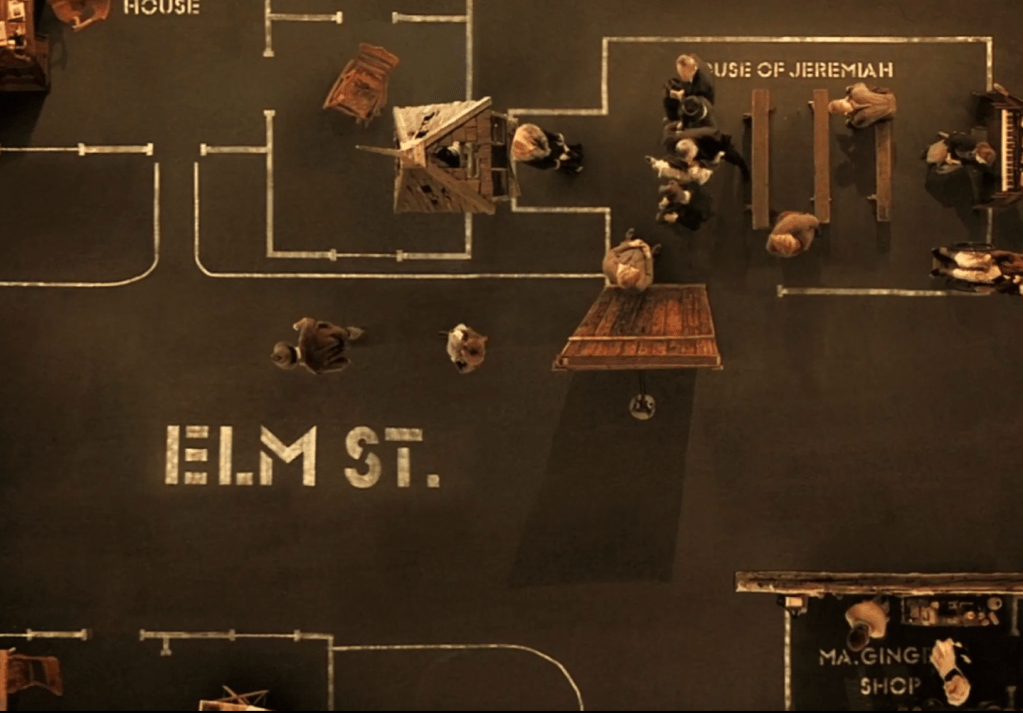

Most of the mothers I interacted with at the shelter were contending with partner violence in addition to low wages and for some of them, this violence in conjunction with poverty was the reason they no longer had a place to live. It takes resources to escape violence, be it in the war zones between patriarchal governments, or in the war zones of the patriarchal family. The walls of the biological family are a fractal of national border walls. The wall between concentration camp and Nazi family in The Zone of Interest demonstrates that function of the familial to not only delimitate who one is responsible for, but to delineate those beyond that wall as prey. Compare Lars von Trier’s elimination of physical walls to reveal the blueprints of violence as inscribed into the very ground of domesticity, as a war of micro-borders, in Dogville.

In relation to these borders, Sontag’s essay takes up the suffering of nation-state war. She herself risked her life in Sarajevo to stage Waiting for Godot. These proximities circle each other in this work of hers: making a study of pain and its representations and trying to alleviate and end pain in part by thinking about how representations of pain galvanize, numb, or stifle our capacity to act, then staging a play which represented what Sarajevan people endured, waiting, waiting, waiting for Godot–waiting for help while the killing went on. Bringing herself to the scene to make a difference that made a difference, within the limits of her capacity.

How might we understand this cliché, ‘making a difference’? Difference is otherwise. What kind of otherwise do we mean to shape when we intend to ‘make’ a difference? When a difference is needed, we speak of making it. A difference must be made; forged; constructed.

Is making not, when it comes right down to it, a physical act?

Years ago, not long after Bush’s invasion which millions all over the world tried to stop, and which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, I had a dream that I have never forgotten. I was in Iraq. As in so much red-lit footage of the war, in my dream, American soldiers had invaded a family’s home in the middle of the night. Children cried as the soldiers moved quickly through their homes shouting, weapons out. In horror, I tried to stand between a soldier and his gun as he shot at a young girl, but the bullets went right through me and into her. I wasn’t there.

Where there should be protection, a boundary: none. Where there should be openness, flow, interchange: walls.

As Gaia Vince and Sonia Shah have pointed out there are more border walls on the planet now than there have ever been, in this time of resurgent religiosity. Religion, the etymology of which is religare, meaning to re-bind, or bring together, is instead hystericized to justify violent cleavages and separations. The most valuable contribution of “world religions” and perhaps the only thing worth salvaging from monotheisms: universal camaraderie and hospitality based on the universal condition of interdependency, in an ultimately mysterious cosmos. In this sense every politician “of faith” who doesn’t prioritize housing for all and assents to the militarization of borders and the construction of walls is in fact faithless and a hypocrite.

Yet there are still those who hearken back to the root meaning of religare: at the core of the work of courageous, prophetic organizations like Street Retreat, or Religious Witness, founded by Sister Bernie Galvin (as well as secular groups like Cop Watch and others) is the practice of being present to bear witness, altering time and space which alone can prevent abuse. Here, sacred space is not located in a building. The sacred is found in that loving meeting that re-binds those who have been separated. In this sense the sacred is an act, not a domain. These small, local actions of a few, planned and unexpected, organized and spontaneous, bridge separations, in this case to build solidarity between those with places to live and those without, alleviating suffering for a moment, for a time, for a person, or a group of people, sometimes resulting in forms of friendship, accountability, and policy change that can help at a broader scale.

Perhaps police continue to exist to the extent that we see ourselves as responsible only for family, and sometimes barely that. How can there be a dissolution of police, in this sense, without an expansion of the definition of kindred to include everyone? What becomes visible in the “street sweep” (nomenclature which designates people on the street as detritus) is the way in which police are used to make the suffering of those without places to live less evident, for the emotional and logistical convenience of those with places to live. If the latter will help carry the burden, let the weight be distributed, see themselves as enactors of social care–through policies that strengthen social services, yes, but also through practices of embodied presence–the police might be obviated.

Author bio: Miranda Mellis is the author of Crocosmia (forthcoming 2025, Nightboat Books), The Spokes, The Revisionist, None of This Is Real, Demystifications, and a number of chapbooks including, most recently, Unconsciousness Raising & The Revolutionary. Raised in San Francisco, she now lives in Olympia and teaches at Evergreen State College. http://mirandamellis.com