By Payton McCarty-Simas

McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) Robert Altman’s seminal revisionist Western tragedy (recently re-released on Blu-ray by Criterion), was originally just called McCabe. This name change speaks volumes about the film, which is, above all else, an examination of the ties that bind women to their own subjugation. It’s a quiet, melancholy film that hinges on the choices McCabe (Warren Beatty) makes in arrogance, but that he never has to live with. Once the smoke clears at the film’s conclusion, McCabe’s seemingly inevitable, hubris-fueled death, it’s the unmarried Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie) who must face the consequences. Mrs. Miller, who uses the marital honorific like a shield against the dangers of single womanhood, is the beating heart and driving force of the film. Her story is a subtle feminist tragedy, an addiction story that presents enforced feminine (and masculine) performance as self-immolatingly rigid, bringing out modern dynamics around gender roles, sex, consent, and substance dependency from its frontier fable frame.

As a madame in the town’s brothel, Mrs. Miller is an outlier and a force to be reckoned with. She maintains a position of power by playing virtuosically with gender, managing traveling in masculine spaces and effectively running her own business in a semi-respectable manner without actively performing totalized masculinity. In a desolate landscape made up of mud puddles and saloons, this specifically dual role is where she’s most comfortable, maintaining her individuality in hyper-gendered spaces. She’s first shown coming to town in a formal dress and bonnet, a stark contrast to the other women — all either sex workers or frontier wives in ragged slips and shawls — and orders tea while the men drink whisky. That said, she radically breaks the expectations set by her appearance and gender by ordering herself a large breakfast and eating ravenously while offering McCabe a business partnership — an offer which hinges on the fact that she, as a woman, can’t raise enough capital on her own to start her business alone regardless of her drive and intelligence, a point that lies at the heart of her character.

Mrs. Miller relies on combined masculine and feminine traits, using them to her strategic advantage as a means of advancing in her social world: When McCabe prepares to reject her offer of partnership, she delivers a powerful and direct monologue, asking, “what do you do when one girl fancies another? When they stop getting their monthlies — which they will?” Upon receiving only dumbfounded silence from McCabe in response, she finishes by asking him whether he’d be willing to inspect his customers’ genitals for signs of sexually transmitted disease, a prospect at which he vocally demures. Her knowledge, inherent to her role as a sex worker with experience, in tandem with her intelligence, superior math skills, and (ironically masculinely-coded) business acumen, add up to her temporary triumph as she persuades him to give her the position.

However, McCabe’s macho pride and expectations of firm boundaries between “men’s” and “women’s work” not only lead to his own brutal demise, but to Mrs. Miller’s ruination when their business is forcibly taken from them by powerful men. Where Mrs. Miller is defined by strategic gendered code-switching, McCabe is shaped by his inability to perform “forceful” masculinity, while retaining a hubristic, rigid, macho stance. As the film progresses, he insists on making the primary business decisions. This is in reaction to Mrs. Miller’s refusal of his romantic advances in favor of a more sexually and economically-based relationship. Mrs. Miller’s financial priorities further rankle McCabe: she chooses to spend money on “frivolities” such as bathhouses which he deems unnecessary. Ultimately, Mrs. Miller’s intuition proves correct, as these feminine touches appeal to clients who, in absence of wives, understand the brothel as an intimate, domestic space.

Despite her business acumen, however, the unmarried Mrs. Miller can’t escape her entrapped state of womanhood, only distract herself from it with drudgery or numb its effects with drugs. When sober, Mrs. Miller never smiles around men. She is gruff and brash and goal-oriented, treating the men around her, even her closest friend and lover McCabe, as a means to an end. Her transactional stance proves that the bind keeping her fellow sex workers entrapped holds her as well.

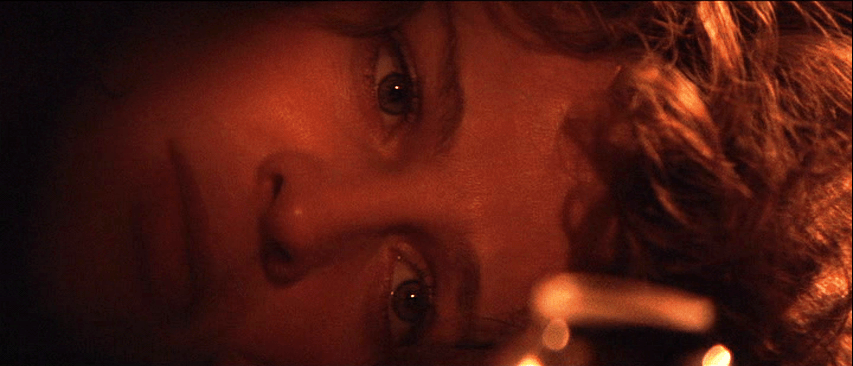

She turns to opium as a salve for this captivity. Only under its thrall, can she consent to sex with McCabe. The meaning of this tragic coping-mechanism is made clearer when, at the beginning of a scene, McCabe interrupts her pipe-packing by bringing her flowers. We can see by her loosened hair during this ritual that her drug use is her escape, a means of softening herself in a hardened world. Only after she smokes is she able to perform femininity for McCabe as his lover. After rebuffing McCabe sober, Mrs. Miller lets her hair down, smiling broadly and giggling. Her face softens and glows, and her eyes sparkle with angelic light. Mrs. Miller’s substance addiction in the film, then, is clearly connected with her need to perform femininity as a means of survival. Opium allows Mrs. Miller enough artificial emotional distance and passivity to fulfill her role as an unmarried woman seeking independence. This balance is crushed by McCabe’s death. Now that her hopes for a financially independent future are dashed, she fully succumbs to her addiction, becoming a passive character.

While Mrs. Miller is able to find solidarity and emotional connection within the confines of exclusively female spaces like her brothel, her gender hinders her in hostile masculine arenas. As McCabe’s jealousy and impotent frustration grow, Mrs. Miller’s reluctant reliance upon him becomes her downfall: she is forced into a passive position, wasting away in an opium den, completely powerless to control her circumstances, defeated by the knowledge she is unable to succeed in the male world without McCabe to open doors for her by providing masculine legitimacy and capital to her enterprises. She performs artificial femininity — her role as a passive lover to McCabe — as a means of furthering her ends, but struggles with the expectations these roles impose. While Mrs. Miller succeeds in overcoming much of the passivity stereotypically mandated by her gender in her role as McCabe’s business partner, her world is fundamentally and intractably limited by these expectations.

Author Bio: Payton McCarty-Simas is a freelance writer based in New York City who loves all things horror. Their writing has been featured in The Brooklyn Rail, Film Daze, and Bright Lights Film Journal among others. Their first book, One Step Short of Crazy: National Treasure and the Landscape of American Conspiracy Culture, is scheduled for release in November 2024.