By Tyler Thier

This is a manifesto against cute animals. The kind that nameless sponsors of “art” force-feed us within their insidious narratives. The kind that Scooby-Doo-react their way to an erasure of our critical faculties. The kind that meow, purr, woof, ruff, chirp, squeak and grrr straight to our wrists, cuffing them tightly, policing our spectatorly bodies to feel what the corporate machinery wants us to feel. Then straight to our throats, clasping shut the esophagus until only verbiage that upholds the commodity can escape. There is no longer a synapse, a Brechtian proscenium to healthily separate us from the content we consume—the cute animal has demolished it. It’s made us one with the vector.

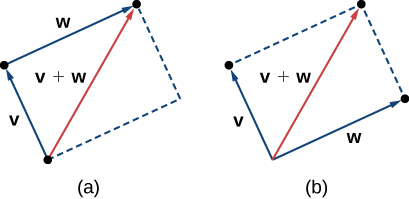

Vector. A dense word, an enticing word—scary, even. McKenzie Wark classifies it as “any means by which anything moves. Vectors of transport move objects and subjects. Vectors of communication move information.” It seems this vector she articulates is what Gilles Deleuze earlier prophesied as a post-factory, bureaucratic hell fueled by micromanagement and a sense of endless work, a corporate nebula of “perpetual training.” It may not even be apt to call it a system of “post-capitalism,” but rather something entirely its own, and cute animals are a crystalline variation of it. They act as vessels through which financial intent for consumer enjoyment is transmitted. Something of some consequence just happened on-screen, but instead of reacting to it on your own terms, here’s an adorable little creature to do that for you. Perpetual training even in what you watch for leisure. Perpetual training for a product, for efficiency, for smooth consumption without critique.

This is heady stuff, but here’s my assessment: we no longer reside within a clearly unfair hierarchy, but rather a murky system whereby hierarchy is altogether disguised and rendered intangible – yes, stronger and more unfair than ever before. The “disciplinary societies” (as coined by Michel Foucault) of the early Industrial Age were enclosures, says Deleuze, or “molds, distinct castings.” Where we find ourselves now, however, is a labor and consumption ecosystem that acts more like “a modulation, like a self-deforming cast that will continuously change from one moment to the other, or like a sieve whose mesh will transmute from point to point.” The elite do not only gatekeep wealth and reward, but also, now, the capacity for information of such a reality to even be processed and understood. If you control information, you control perception, which leads me to the visual apparatus that upholds this ominous vector.

Mainstream film is a particularly insidious way for corporate greed to domineer consumers. Need I mention the intricate, multi-level (both in marketing and in worldbuilding) business scheme of the Marvel Cinematic Universe? Or how about A24’s “pop arthouse” branding, one which styles them “as much like a design firm as a film studio.” But what all of these mass-market franchises and milked-to-death IP have in common, more intrinsically than one might realize, is what I’ll call the “cutesy animal emote.” In family comedies, these take the form of expressive, sometimes fully sentient, house pets; in Star Wars, it’s the bumbling droid characters like BB-8 and alien species that don’t resemble human beings, like Porgs and Grogu; in Marvel, it’s the CGI extraterrestrial cat named Goose, or Vin Diesel’s easy paycheck as the voice of Groot; in Disney animated content, it’s usually a much smaller, much cuter, and sometimes even sagacious traveling companion to the more assertive and instinctual protagonist; and something like the Kevin Spacey-starring Nine Lives is simply too confounding and upsetting to articulate here.

Instead, I’ll train my microscope on a more recent, and much more cynical, CGI cat: Alfie, the digitally generated monstrosity of a furry companion, from Matthew Vaughn’s Argylle. The plot is a blur, but a basic distillation is that a spy fiction author’s narratives (the titular Argylle series of books) begin to manifest in her reality. She is thrust into a globetrotting espionage plot of her own making. It’s a cinematic war crime–fitting for the times, as that’s all that seems to be happening around us. This case study will hopefully cast the points I’m trying (and probably faltering) to make in sharper perspective, because Argylle runs with the cutesy animal emote to nefarious lengths.

Let’s return to some of the theory for a moment. Guy Debord, in his definitive The Society of the Spectacle, draws from Bertolt Brecht’s idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk and Siegfried Kracaur’s cult of distraction. The spectacle, he describes, “is not a collection of images; rather, it is a social relationship between people that is mediated by images.” In other words, it’s not an adornment or accessory – an external appendage – but rather the very essence of

society’s real unreality. It is the omnipresent celebration of a choice already made in the sphere of production, and the consummate result of that choice. In form as in content the spectacle serves as total justification for the conditions and aims of the existing system. It further ensures the permanent presence of that justification, for it governs almost all time spent outside the production process itself.

When one enters the blast radius of a piece of media that may be classified as spectacle, critical thought is extinguished. The choices that went into making that visual product are so intertwined with the motives for profit, enterprise, and untampered success that the film itself operates not as art but as advertisement. No, not even entertainment or escapist fun – the spectacle as theorized by Debord is a totalistic mediation of our viewing responses. It would actually be too easy to liken this kind of creation to propaganda, because it’s not even reactionary; it’s reactionless in that it essentially fills a prescription. Once consumed, this cinematic pharmaceutical signals reactions in our place. It takes the reins.

Funnily enough, Bryce Dallas Howard’s spy-fiction-author protagonist in Argylle is handled like a dog on a leash, a leash commandeered by a cat. The latter is cozily situated, like the Wizard behind emerald curtains, inside a retro 60s looking backpack with a transparent dome through which to emote. Alfie, then, is the audience’s roadmap through the film’s unintelligible setpieces, mounting Howard’s main character so that we always, with no choice, have our cutesy animal companion to show us (coincidentally, this in fact tells us) how to respond to the unfolding events. And when he’s let loose from that little pod? Forget about it. All potential for thinking for ourselves goes plunging to its death as quickly as Dua Lipa was introduced and killed off. This last point was indeed the only reason I went to see Argylle in theaters, but when Dua was offed in the first 10 minutes, I realized there was still 2+ hours to go. I haven’t been the same since that moment; it made me a full-blown nihilist.

The animal emote functions cinematically as the emoji does textually. The latter gives a sense of absolution to words, so you’re not left necessarily to infer the tone in which they’re meant to be read. The danger with the former, however, is that it serves to intensify that which is already communicated through the tapestry of, among others, diegetic sound, dialogue, action, and cinematography. Argylle – I notice more each time I type this title how stupid its spelling is – already melds language with visuals. It’s a mainstream blockbuster, albeit by a director with a particular style and sense of madcap antics in his body of work. And that’s exactly the core of his latest film’s problems: it applies a barrage of Alfie’s emoting and other arbitrary signposts while already anchoring itself in a “silly,” “overblown” aesthetic. It attempts to pass as cheeky and knowing in its absurdity, and yet constantly plays it straight within that conceit.

I can almost forgive other titles that are blissfully ignorant of their thought crimes against the spectator. Countless family films with cute animals, like Dog or Tangled, at least bear sincerity and humble aspirations in what they’re trying to achieve; they’re not trying to be anything greater than the feel-good, popcorn fodder that they are. Vaughn can’t feign the same excuse, because he’s aiming for a bombastic, large-scale espionage satire. Why, then, does he insist on ultra-CGI? Some of the most classic spy films are steeped in practical setpieces. Why, on top of that, does he insist we spend time with grating characters who aren’t funny or at all reminiscent of archetypes in the genre, and, at the center of them all, a corporate mascot in the form of a feline pixelation.

This piece is becoming more of a theoretical tract, a rant with some philosophy in the mix, than a careful study. Maybe it’s just a tangent all around, but you know what? I think that’s ok because Argylle doesn’t deserve my close analysis, let alone the time of day. I will, however, start to wrap up with a half-assed example of Alfie wreaking his havoc.

This movie left my brain immediately when the credits rolled, so I neither know nor care how we ended up with the main characters (Howard and Sam Rockwell…I think?) jumping onto a barge on which Alfie has already landed. Their impact sends the cat flying, straight into the frame of our overhead camera, which means straight into our faces in the theater. He even lets out a disconcerting meeeoowwwwwww. Yes, this is one of the few scenes I remember because it makes me gutturally, animalistically angry. It had already done so in the trailer weeks before I saw the film in its entirety – and seeing it in the context of the “plot” made it even worse. It has nothing to do with anything going on in what is just a convoluted string of misadventures and excuses to make a music video out of action-heavy moments, other than demand that we “find this funny. Right? Haha. You know you want to laugh or gasp in amusement. So do it. Now.”

Debord, were he alive, would editorialize this as

the spectacle manifest[ing] itself as an enormous positivity, out of reach and beyond dispute. All it says is: ‘Everything that appears is good; whatever is good will appear.’ The attitude that it demands in principle is the same passive acceptance that it has already secured by means of its seeming incontrovertibility, and indeed by its monopolization of the realm of appearances.

This is the reality of the unreality, or vice versa, encapsulated in Alfie. The desire for big business, the power of corporate sponsorship of art, to sway reception towards uncritical enjoyment. The production choices to shoehorn in a cute animal as a mascot who will act either to comfort the audience in moments of violence, or hammer home a feel-good aura when what is happening before the cut-to-emote is already feel-good. And Argylle does this all while making us believe (“monopolizing its appearance”) that it’s a smart, subversive genre deconstruction.

Full-circle, now, we arrive back at Wark’s vector and Deleuze’s modulations. If “perpetual training” – the appearance of a flexible labor reality in an all-consuming digital workplace – is becoming the norm, then we had best be concerned. Argylle is a visual mediation of this via spectacle, via emote templates designed to make you react in ways only a financial stakeholder would expect. The endless workday is one thing, but media’s upholding of it makes it a whole different monster, so with Argylle as a perfect example, mainstream products have begun modulating themselves into anti-mainstream, anti-sanitized facades. Under that rancid hide, however, they remain a hyper-mainstream, hyper-sanitized commodity. Corporate principles and aesthetics are thereby perpetuated, and most of us will never notice it.

Vaughn’s film is a failure. Yes, I mean that objectively, and if you don’t agree with me then why are you still here reading this? It’s a failure commercially, thankfully enough (although I’d argue it didn’t deserve a penny), and it’s a failure artistically because it’s not about pleasing the audience. It’s about pressuring them into pleasure based on pretense. Whoever held financial power over Argylle’s creation controlled the vector through which messages or styles or jokes could be communicated, and Vaughn executed it within the constraints of that very vector. Sure, that’s the case with almost anything, but what makes Argylle’s vector so malicious is that it’s masquerading as absurdity. When the only absurd thing about it is how it doesn’t trust its audience to see through its bullshit. Spoiler alert: we have.

Author Bio: Tyler Thier is an academic and freelance critic based in Queens, NY. His writing can be found in various places, including Aeon, Senses of Cinema, and wig-wag, and he specializes in maligned, dangerous, and otherwise controversial pieces of pop culture and media. His least favorite movie of all time was Joker, until its recent sequel dethroned it.