By Vienna D’Angelo

Weathering With You’s uncanny resemblance to my dreams drew me in right from the start. The second scene mirrors my recurring ferry dreams—a relic of my youth in the Pacific Northwest. It shows a boy embarking on a new life in a new city, taking a ferry through a strange weather event that enthralls him with its sublime beauty, only to nearly sweep him overboard, putting him face to face with subsumption and death.

Makoto Shinkai’s Weathering With You blends romance and catastrophe with a magical twist, reflecting Japanese tensions between holistic spiritual tradition and capitalist modernity while also making visible a global condition in which industrial life butts up against ecological disaster. The persistent rainstorm threatening to flood Tokyo evokes the Edo Period transformation of Edo into Tokyo, with its bay filled to enable urban expansion. This “oceanic” subsumption operates not only literally but metaphorically, conjuring personal and societal transformations. Weathering With You uses “oceanic” affects to convey an abolitionist horizon against normative attachments, including “work” and “the family,” while risking oneself for a better collective life.

The film follows Hodaka Morishima, a runaway navigating Tokyo’s precarious underclass without an ID, and his eventual love interest Hina Amano, a Shinto weather-maiden with the power to summon sunshine through prayer who is initially working at McDonalds and in the process of being coerced into working at a Hostess Club. Hodaka uses a Chekov’s gun, in actuality a Makarov, to help Hina escape from the latter. As for the former, together with Hina’s younger brother Nagi, they use Hina’s power to lift themselves out of poverty. However, the magical sunshine comes at a cost: Hina must be sacrificed to end the ceaseless rainstorm threatening to flood Tokyo entirely.

This dilemma is not entirely novel. Dostoevsky uses the suffering of an innocent child in The Brothers Karamazov to condemn society’s failures, troubling the goodness of God, and questioning utilitarian logics. Perhaps more relevant is Ursula K Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas,” which presents an ambiguously desirable society which verges on utopian, but is predicated on the suffering of a single innocent child. This suffering is a sort of public secret that people either choose to dissociate from, or as the title suggests, walk away from into some dark unknown. This resonates with the choice present to Hodaka and Hina. Perhaps theirs is an even easier choice, as our lived reality is typically less desirable as their lifeway is under attack by the state, but the question remains, “What price wonderland?” At what point do these fantasies of the normative good life and calls to not rock the boat become what Lauren Berlant calls, “cruel optimism”?, by which they mean, “…something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing.”

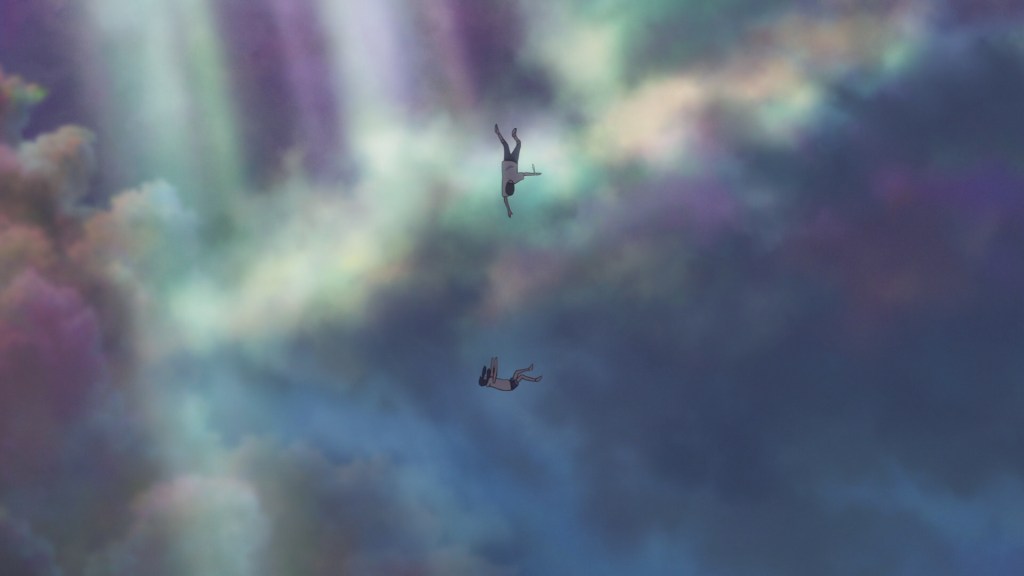

Initially, even Hodaka resigns himself to Hina’s fate, succumbing to narratives imposed by authority figures. Yet his love for Hina, and their shared vision of a life together, prompts him to reject this sacrificial logic. Defying societal control embodied by the police, Hodaka rescues Hina, allowing the rain to continue and thus Tokyo to flood. Their decision exemplifies an embrace of a communistic form of “the oceanic”—a transformative rupture and subsumption that leads to more holistic modes of existence.

The concept of the “oceanic,” as discussed by Jackie Wang (drawing from Rolland and Freud), refers to a profound, affective connection to something larger than the self—a boundless and interconnected sense of being that transcends individuality. In Weathering With You, this notion operates both literally and metaphorically. The persistent rainstorm and eventual flooding of Tokyo stages a transformative rupture, disrupting the boundaries of the city and its people. This flood is not merely a disaster but an invitation to dissolve rigid structures and embrace immanence—a sense of belonging to the chaotic, unpredictable flow of life itself. For characters like Hodaka, Hina, and Suga, the oceanic represents an opportunity to reconfigure their lives around mutual care and solidarity, rejecting the isolating imperatives of capitalist modernity. ‘The oceanic” thus becomes a lens for imagining non-linear, anti-normative futures where individuals and communities adapt, transform (risking themselves in the process), and flourish within the larger, uncontainable forces of their environment.

The embrace of the oceanic is poignantly illustrated through Keisuke Suga, Hodaka’s boss and reluctant father figure. In a moment of surrender, Suga opens a sub-street-level window, allowing water to flood his apartment. This act transforms a cluttered space frozen in grief into one washed clean by rainwater, symbolizing release and renewal. Here, the film suggests that integrating oneself into immanent, chaotic forces—rather than resisting them—can create space for transformative healing.

This theme recurs in Hodaka’s reading material, which shifts from Catcher in the Rye—a story obsessed with preserving innocence—to an article on the anthropocene, echoing the ecocritical communism of Kohei Saito. Saito’s work advocates for radical societal change through collective ownership and degrowth, rejecting linear, capitalist futurities in favor of holistic, non-utopian lifeways. Similarly, Hodaka and Hina’s rejection of sacrifice represents a break from normative trajectories, imagining a submerged Tokyo not as a disaster, but as an opportunity for reimagined collective lifeways.

Watching this movie I saw Kathi Weeks’ The Problem with Work flash warning lights in my brain. Her book critiques the capitalist imperative to organize life around productivity, often at the expense of human flourishing, and provides a troubling lens through which to view this film. Hina’s prescribed sacrifice exemplifies this logic: her life and labor are reduced to tools for sustaining an oppressive system. By refusing this demand, Hodaka and Hina affirm the possibility of flourishing beyond normative and capitalist paradigms, shifting their priorities toward care and mutual aid. Their defiance, in a sense, embodies Weeks’ gestures towards post-work futures, where productivity ceases to dictate the terms of existence, but also highlights the perniciousness of work. At the very end of the movie the disposition towards work shifts, decentering it, but Hodaka still casually remarks he has to pick up a job, implying capitalism still rules over the flooded world.

Another valence I could not shake from my thinking about Weathering With You comes from M.E. O’Brien’s Family Abolition and its critique of traditional family structures. In the film, Hodaka, Hina, and Nagi form an affinity-based grouping rooted in care and solidarity, challenging the family as a site of capitalist reproduction. Their chosen kinship contrasts sharply with Suga’s estrangement from his daughter, highlighting how normative familial structures often fail to fully actualize their animating desires under capitalist pressures. While not entirely free from familial trappings, Hodaka and Hina’s grouping imagines a future where solidarity transcends biological or hierarchical ties, aligning with O’Brien’s call for liberatory forms of care. There’s even a moment where Keisuke Suga more firmly adopts the role of a paternal figure and tries to talk Hodaka down from rescuing Hina, attempting to convince him to turn himself over to the pursuing police. Ultimately Suga is shaken from this disposition by Hodaka’s impassioned cries, clashing with the police himself to give Hodaka an opportunity to escape. All of this reveals the inherent repression of the normative ruling order which asks us to go along with it because “everything will work out,” all the while being predicated on actively destroying that which holds the seeds for a life worth living.

Says Fredric Jameson: “Someone once said that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. We can now revise that and witness the attempt to imagine capitalism by way of imagining the end of the world.”

The world smashing disaster is already here—it’s the twin demons, the state and capitalism. The revolutionary move may indeed look more like Walter Benjamin’s analogy of “the emergency break.” The elephant in the room is the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant disaster that, according to theorist Sabu Kohso in his book Radiation and Revolution, was followed by an explosion of radical activity. This continued uptick in radical activity allegedly came as the event challenged meta-narratives about the state and industry and resonated with previous moments of disaster that shattered meta-narratives like the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as events not dissimilar that were accompanied by state misinformation like the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. For their part, after Fukushima, Kohso and his comrades began to focus on anti-capitalist social organizing in East Asia more broadly and even networked with radicals in the Pacific Northwest as part of their attempt to undercut imperial and nationalist formations and reorient around geographic flows which still function to this day. It suffices to say, Weathering With You seems to tap into these currents, whether consciously or not.

By weaving these theoretical frameworks into its narrative, we can see Weathering With You as a challenge to normative demands of capitalist work, sacrifice, and kinship, instead embracing oceanic ruptures as pathways to transformation. The film’s submerged Tokyo invites us to reject linear, capitalist visions of the future in favor of collective lifeways rooted in care, solidarity, and renewal. Ultimately, Shinkai’s work asks how we might navigate our own storms—defying dominant narratives to chart new, transoceanic trajectories toward collective flourishing.

Author bio: Vienna is a critical theorist who has returned to academia after a half decade stint as an informal care worker, and a life of attempted radical praxis, in hopes of becoming a teacher and bettering their writing. Most of the articles and communiques they’ve contributed to have been anonymous so far, but you can find some of their writing in Deceiving The Sky: Collective Experiments in Strategic Thinking and in the future in Baedan 4. Currently Vienna is focusing on creating a synthesis of queer, operational, and affect theory. They also like thinking too much about movies, and video games.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011.

Jameson, Fredric. “Future City.” New Left Review II, no. 21 (May–June 2003). https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii21/articles/fredric-jameson-future-city.

Kohso, Sabu. Radiation and Revolution. Duke University Press, 2020.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011.

Le Guin, Ursula K. “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” The Wind’s Twelve Quarters, Harper & Row, 1975, pp. 275-284.

Nishiyama, Kazuo. Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600–1868. Translated by Gerald Groemer, University of Hawai’i Press, 1997.

Well written and thought provoking. I look forward to watching the anime.

LikeLike