By Cameron Metcalfe

During a press interview promoting The Witch (2015), director Robert Eggers was asked about audiences’ assumptions that the film depicted “female power” and a feminist political message. His response to these claims was “I didn’t need to weave [feminism or female empowerment] in, and I was trying to not do anything intentionally. It just happens” (St. James 2016). Indeed, it is a staple of contemporary feminist horror—loosely defined as horror produced in the 2010s to the present depicting the “inherited oppressive conditions of the housewife” (Isaacson 2) under modern constructions of feminized labour and economic precarity (7)—that the “monstrous feminine” can be used to highlight the “monstrous masculine.” Feminist horror also often complicates feminine “monstrous” depictions by juxtaposing them with the sinister structural socio/economic/cultural patriarchal forces which create monstrous women in the first place. In other words, the stories we tell today about women’s monstrosity still serve a didactic function—one that may shed light on how monstrous women are constructed by a patriarchal society that fears women’s empowerment.

The two texts that this essay will address, consequently, utilize historically-rooted conceptions of witches to frame their narratives in an attempt to tell a modern feminist story. The Witch (Eggers 2015) is unique within the subgenre of feminist horror (if it can be labelled as such—a question that is of importance to this essay) for its dedication to a historiographic setting uncommon to most other feminist horror. Caryl Churchill’s play, Vinegar Tom, despite sharing a similar dedication to historical accuracy through its use of primary historical texts (sometimes quoted directly), conversely lacks the feeling of realism that The Witch aims for. Yet, it is decisively a work of feminist fiction.

Because of this, I argue that calling The Witch a feminist film is a reflection of our modern cultural attitudes rather than an endemic quality of the film and that Vinegar Tom’s foregrounding of modern feminist critique against the backdrop of the historical witch craze operates ironically under modern theatre’s general allegiance to anti-realism. As we shall see, there is nothing empowering about Thomasin’s story, and the film’s requirement that audience members buy into Puritan ideology in order for its scares to operate successfully, ironically suspends critical gendered consideration. In other words, the more one treats the film as a horror film, the less feminist it becomes. Vinegar Tom, contrarily, elevates its historical source material to the gendered consciousness of its modern audience, signaling a very different approach to the use of historical material in fiction. Genre convention, therefore, lies at the heart of how these ostensibly similar texts operate differently. Horror’s emphasis on visuals to stimulate fear and disgust, and theatre’s emphasis on dialogue to stimulate thought and criticism, necessarily provide disparate levels of gendered criticism.

Puritan Horror for a Modern Audience

As explained in the previously mentioned press interview, Eggers took great pains to use period-specific materials and construction methods to create the set and costumes and, as the film’s final card reveals, the dialogue was sourced to varying degrees from the journals and writings of Puritans who inhabited New England in the 17th Century. The film, then, despite the fantastical depictions of literal witchcraft, demonic possession, and the corruption of the Devil, ironically presents itself as a realist horror film in its quest to capture the qualia of devout Puritan life in the American wilderness. Eggers is, ultimately, attempting to transport the viewer into the ideological reality of Puritan fears of witches, rendering them as horrifying monsters who kidnap children in order to harvest their viscera to abate the deterioration of their hag-like bodies. Fascinatingly, for the ‘scares’ to work, the film asks its audience to buy into a centuries-old religious ideology that treats witches and the Devil as very real, making fascinating grounds for questioning precisely what makes a film ‘feminist’ or not.

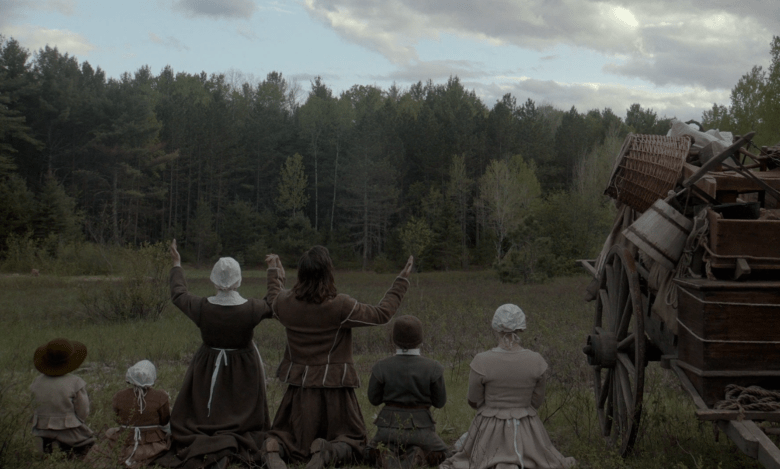

Despite the claims that the film espouses a feminist outlook, the more one regards The Witch as a horror film the more it becomes a parable about the folly of men. Certainly, if we were to transport a seventeenth-century Puritan patriarch into a theatre to watch the film, he might (after recovering from the shock of seeing women’s naked bodies and witchcraft) be utterly horrified by the apostate patriarch character William’s religious hubris that ultimately exposed his family to such wild, feminine dangers like a witch of the wilds. “You aren’t honouring God!” our Puritan time traveller might (rudely) shout in the theatre as the family raises their hands together in prayer at the site of their new isolated home (while ironically prostrating themselves before the woods where the witch dwells), “you have willingly stumbled into the Devil’s nest!” Indeed, William’s proclamation that “we will conquer this wilderness; it will not consume us” speaks to the horror of patriarchal hubris in the face of isolation from the protection of the group.

Consequently, the film presents a narrative akin to Greek tragedy (the Greeks, of course, being no strangers to the conception of the family and polity uniting patriarchal dogma against women’s rights and interests). William’s maltreated daughter Thomasin’s transformation into monstrosity at the end of the film can thus be read in this context as a natural and presumed consequence of the patriarch’s failure to maintain a tight grip on their household (i.e. the women and children under their charge) when he eschews the communal bonds of religious community and structure. Of course, for the scares to operate under a realist framework successfully, the audience must divest themselves of their disbelief in Puritan constructions of witches—a state that necessarily privileges a reading of the film that focalizes William’s tragedy. How can the witches in the film instill fear when our ostensible heroine Thomasin becomes one at the film’s end? The horror and feminist outlook are thus in tension with one another.

Today’s audiences, to give them credit, might be more likely to appreciate the ways in which Thomasin’s (literal) ascent into becoming a witch at the climax of the film is an empowering act against the backdrop of patriarchal control that scapegoats her. Indeed, this reading is signaled by the film despite Eggers’ allegiance to historical realism. We might recognize, for example, that the film’s males are criticized — Caleb’s success in lying about searching for apples in the woods reflects his father’s lying about a missing silver cup. Both characters escape punishment for their sins. All the while, Thomasin is consistently blamed for things she never did. Her transformation into a witch at the film’s climax can thus be seen as an empowered act—an escape from Christian-based patriarchal familial control.

Upon closer inspection, however, we get the sense that Thomasin never actually gains autonomy at any point in the film. As Zwissler convincingly argues, the Devil’s contract is just another form of patriarchal control that is mirrored by William’s behavior toward his daughter. Both are vying for control of Thomasin because, as a woman, she is the property of men whose ownership can be bartered (Zwissler 7-8). For example, when William pleads to his wife: “What dost thou want, Katherin? Tell me and I will give it thee!” he is expressing a near-identical bargain (that she shall consign her name to the Devil, not dissimilar to the signing away of one’s name to a future husband) that Black Philip later presents to Thomasin. Power in the film is thus found in the ability to ‘give,’ a power that only patriarchs can bestow. As we shall see, the level of autonomy afforded to Thomasin in the film ultimately betrays any attempts to render the film’s conclusion as happy or feminist-empowered.

When the (Puritan) Woman Looks

As Zwissler helpfully explains, critical assessments of the film hailing it as “a high-powered feminist manifesto” because Thomasin’s ‘choice’ to become a witch “was the first choice she really got to make” (6-7) is ahistorical in its ignorance of 17th century beliefs concerning witchcraft being the result of Satanic servitude and indebtedness (9). Additionally, the claim that Thomasin is liberated is firmly rooted in modern second-wave feminist reclamations of witches as Pagan practitioners of Wicca (13). Such revisions of historical realities are unhelpful when analyzing the film because not only is Thomasin disempowered by her historical context, she is also disempowered through her characterization within the film itself.

To understand just how disempowered Thomasin is as a character, it is helpful to understand how the film communicates her objectified state and stark lack of voice and autonomy. Her presence as seen through the eyes of male characters is scopophilic, either as an object of male voyeuristic sexual fantasy, male domination and ownership of her personhood, or both, and is subsequently transmitted to the audience through identification with the male characters (Mulvey 13). Of course, her towering patriarchal father views her from a position of authority and ownership, making sure to look at her directly while scolding and exacting his parental authority, but curiously always looking away as she clothes and bathes him. He also hugs her from behind at the film’s apex as he comes to terms with his steadfast belief that his daughter is a witch. Of note here, too, is that the Devil and Black Philip both take their turns gazing at Thomasin with lingering shots of the black sheep staring being interspersed throughout the film and the climax featuring the Devil in human form towering over Thomasin as he offers her a new contract of paternal care. Her brother Caleb, too, contributes to the presence of the male gaze directed at Thomasin as the camera directs both him and the audience to notice her vaguely visible breasts with a close up shot.

However, just as important as the male gaze is Thomasin’s gaze, made passive by patriarchal feminine gendered roles. In the aforementioned scene where Caleb is staring at Thomasin’s breasts, she playfully jests “Why are you dallying?” as she invites him closer to engage in playful tickling. This scene highlights what Linda Williams suggests often occurs in horror films when the female gaze does not align itself with the monstrous other: “she is portrayed as ignorant of sexual desire altogether. She is like the one virginal babysitter who survives the attacks of the monster in Halloween” (Williams 28). Indeed, Thomasin is characterized throughout the film by her naivety and passivity. She merely asks Caleb to come along on his trip to the woods without knowing exactly what he is doing. Significant, as well, is that she only voices her frustrations to the children in her family, who frequently disobey and disrespect her orders. Even when she eventually voices her frustrations with the hypocrisy of her father, it only results in her being locked away as the father privately admits to his pride and cowardice: “I beg thee [God] I have not damned my family.”

Perhaps the best example of the passive “female gaze”occurs when Thomasin is playing peek-a-boo with Samuel. The camera faces directly at Thomasin’s face, taking on the gaze of the baby Samuel. What he and the viewer sees is Thomasin as a vibrant motherly figure, smiling and entertaining her infant brother through a game that involves the literal and figurative covering of her eyes. Behind her gaze is thus a girl who knows of nothing but subservience to the needs of the familial unit, at once charged with the protection and care of an infant—the most valuable and vulnerable asset of a family—while ultimately doomed to lose it to the deleterious forces of Satanic witches that she will eventually join.

Contrasting her innocent gaze at her infant brother is the final scene of the film. After signing the Devil’s black book (which as Zwissler discusses only makes her indebted to the Devil), the audience is ‘treated’ to the image of Anya Taylor-Joy’s nude body double (itself a cue that the nudity we are watching is couched in a misogynistic culture obsessed with gawking at the nude female form) walking into the woods where she flies into the sky with her newfound witch coven. We get a close up shot of her face that ambiguously displays either ecstasy or, as Zwissler convincingly argues, madness (Zwissler 8). Despite the director’s intentions, and against the readings of witch-aligned feminist critics, the visuals of this scene ultimately communicate uncontrolled malevolence rather than female empowerment. Thomasin, now granted power bestowed by the Devil under duress (what choice is there, really, when her family has been systematically killed and she now otherwise faces a presumed life of squalor and isolation), and doomed to perpetuate rituals of child sacrifice, becomes an object of the sexualized male gaze as the nude witches float haphazardly in the air. Such an ostensibly drastic rejection of the heteronormative patriarchal construction of the family (which we have previously shown to ironically be a Devilish reflection of the same gendered power dynamics) is merely a reactionary one that neatly confines women’s place as either paragons of familial virtue or monstrous desecrators of ethics and social norms. There is nothing empowering in such a “decision” and critics who espouse Thomasin’s empowerment perpetuate what Williams warned of in her treatise on the female gaze: “What we need to see is that in fact the sexual ‘freedom’ of such films, the titillating [and I would add violent or monstrous] attention given to the expression of women’s desires, is directly proportional to the violence perpetuated against women” (Williams 33).

Women Already Know the Witch of the 17th Century

Caryl Churchill’s Vinegar Tom in many ways provides an antidote for the excesses and indulgences of The Witch. Like Eggers, Churchill weaves in historical documents and theory into her work. She directly quotes and names the Malleus Maleficarum, the primary historical treatise on witchcraft. Additionally, in scene two where Jack and Margery discuss the divvying up and purchasing of land, Churchill echoes Federici’s insights into the land enclosures and monetized economy of the early modern period that contributed to the witch craze and the devaluing of women’s labour (Federici 93-94). While certainly not a work of horror, Vinegar Tom similarly uses historicity and dialogue to suggest that the women of today experience gendered oppression under the same patriarchal norms that generated the European witch craze. Such a sentiment is acutely presented through the character Alice who in so many ways is the antithesis of the naïve Thomasin, although what they share in common is abject powerlessness.

In essence, there is no pretense with Alice. She knows that the Devil is a construction of men, no ‘scarier’ than any other mortal man: “I’ve seen men in black that’s no devils unless clergy and gentlemen are devils” (Churchill 17). Unlike Thomasin, who is tempted with the “taste of butter,” Alice would willingly accept the Devil’s contract with full knowledge of its implications. She wants her Devil-man to take her to London where “Each man has his own religion [… and] there’s women speak out too” (17), and she spends a portion of the play searching for “a man I can have when I want, not if I’m lucky to meet some villain one night” (23). By the play’s end, too, she emphasizes that “I’m not a witch. But I wish I was. If I could live I’d be a witch now after what they’ve done. I’d make wax men and melt them on a slow fire […] There’s no way for us except by the devil. If I only did have magic, I’d make them feel it” (36). Alice, therefore, is a woman who knows full well the historical implications of witchcraft, but chooses to become one out of vengeance rather than self-indulgence. Unlike Thomasin, Alice is acutely aware of the patriarchal forces that oppress her. She wants to fully escape–indeed utterly destroy–the rigid social structures that bind her. Of course, the primary point of the play is that Alice never actually gets the opportunity to sign a pact with the Devil and wreak vengeance upon the men who oppress her—Vinegar Tom, unlike The Witch, is far more concerned with the cynical reality experienced by women.

As the play overall suggests, contrary to Eggers’ claim that “People don’t know what the witch of the 17th Century is at all” (St. James 2016), women today acutely feel the remnants of that period. The songs throughout the play highlight this. The song “Something to Burn” highlights the scapegoating that informs witch hunts: “Find something to burn. Let it go up in smoke. Burn your troubles away. Sometimes it’s witches, or what will you choose? […] It’s blacks and it’s women and often it’s Jews” (Churchill 26). The song “If Everybody Worked as Hard as Me,” too, suggests that women evade such scapegoating and violent persecution through compliance within the heteronormative family: “The country’s what it is because the family’s what it is because the wife is what she is to her man. […] I try to do what’s right, so […] the horrors that are done will not be done to me” (29). Finally, the song “Evil Women” concludes with an acknowledgement that witches are ultimately a construction of men that fill their “movie dream” where their fantasies and fears of women are represented: “Evil women is that what you want? […] Do they scream and scream?” (38). Unlike Thomasin, Alice and women in the real world receive no salvation from the construction of witches. As women they remain a fixture of patriarchal oppression under a system that provides only a binary choice: comply with the patriarchal institutions of God, or blaspheme and become a harrowing pariah under the Devil’s patriarchal control. Whereas The Witch depicts through the realist historical horror genre the fantastical transformative and monstrous power of witches and the Devil that controls them, Vinegar Tom depicts through modernist drama the historical devilish fantasies of men who at once abhor and find titillating the torturing and execution of women who stand accused of practicing witchcraft that has no basis in reality. Which work is more resonant with our understanding of historical realities–and which one is more horrific–is therefore the important question for the reader to assess.

It is overall clear that Eggers and Churchill are representing the history of the witch craze through fictional representations to offer drastically different conclusions for modern theatre goers. That Eggers requires of his audience to disrobe their 21st century secular ideology to play with the horror of Puritan ideology necessarily confuses and obfuscates the real historical gendered politics that it seeks to capture through visual stimuli. Eggers therefore creates a break in the temporal transmission of gendered politics through history as modern critics confuse Thomasin’s assent to witchcraft for autonomous emancipation. Churchill, on the other hand, requires no such investment from her audience. She clearly draws a lineage between 17th century accused witch and modern woman, suggesting that the truth of history is found in poetic dialogue with the past. These diverging approaches to the representation of history in fiction is not new. Both film and theatre, especially, “in ways we do not yet know how to measure or describe [from a historical point of view], alter our very sense of the past” (Rosenstone 1179). It is up to us as critics to tease out these various approaches and illuminate the ways in which oppressive forces of all kinds are perpetuated or obfuscated by our modern fictional retellings of history.

Author bio: Cameron is an undergraduate student in English literature at Trent University in Oshawa, Ontario.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Robert for enlightening me on what is possible when you make connections with professors, Brent for his kindness, support, and introduction to this journal, and Johanna for being the coolest horror/punk pen pal ever and for providing this opportunity. Special thanks goes to Molly for being the most supportive, encouraging, and life-changing professor in the world. Most of all, thank you to Helen (and the cats) for always being there for me.

Works Cited

Churchill, Caryl. “Vinegar Tom.” Plays by Women, vol. 1, Methuen, 1982.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Penguin Classics, 2004.

Isaacson, Johanna. Stepford Daughters: Weapons for Feminists in Contemporary Horror. Common Notions, 2022.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 6–18.

Rosenstone, Robert A. “History in Images/History in Words: Reflections on the Possibility of Really Putting History onto Film.” The American Historical Review, vol. 93, no. 5, 1988, pp. 1173–85.

St. James, Emily. “The Witch’s Director Explains Why Our Ancestors Found Witches so Scary.” Vox, 2016, https://www.vox.com/2016/2/23/11100330/the-witch-review-interview.

The Witch: A New-England Folktale. Directed by Robert Eggers, A24, 2015.

Williams, Linda. “When the Woman Looks.” The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film, 2nd ed., University of Texas Press, 2015, pp. 17–36.

Zwissler, Laurel. “‘I Am That Very Witch’: On The Witch, Feminism, and Not Surviving Patriarchy.” Journal of Religion & Film, vol. 22, no. 3, 2018, https://doi.org/10.32873/uno.dc.jrf.22.03.06.