By William Burns

“There is no sun without shadow, and it is essential to know the night”—Albert Camus

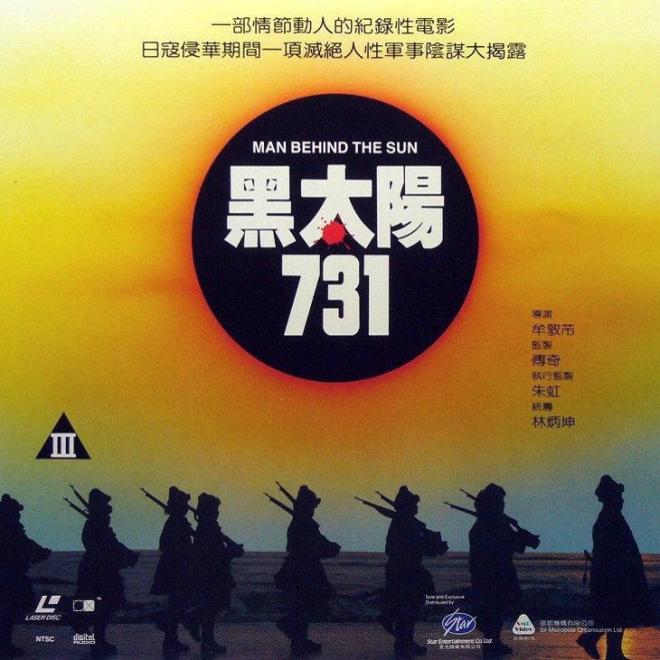

One of the most controversial films ever released (controversial for not only its subject matter but its approach to its subject matter), T. F. Mou’s 1988 film Men Behind the Sun dramatizes events at the infamous Unit 731, a Japanese biological/chemical warfare research squadron stationed in Northeast China that performed heinous experiments on Chinese citizens and Russian P.O.W.’s during World War II. Hiding behind the innocuous title of the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army, Unit 731’s “researchers” tested biological and chemical weapons on imprisoned, kidnapped, and arrested “volunteers” from 1936-1945 with the full support of the Imperial Japanese government. It is estimated that between 200,000-400,000 people died from Japan’s use of these weapons against the Chinese people, with 10,000 “prisoners” dying in the Unit 731 complex itself.

Obviously a contentious subject, Men Behind the Sun has been accused of not only presenting graphic depictions of the tortuously lethal studies, but also of gleefully wallowing in them. Accusations of animal cruelty and the use of actual human corpses have also dogged the film since its arrival in the U.S. in the early 1990’s. (I remember renting a bootleg copy of it from an independent video store and the tape was so degraded that it made it seem even more authentic, like the movie was really filmed in the 40’s). Although the crude special effects are gruesome to the extreme, it’s perhaps the film’s tone of morbid objectivity and nihilistic indifference that is most shocking. And yet Men Behind the Sun offers more than grotesque thrills and “I can’t believe what I’m seeing” moments. The film is actually saying something quite profound about history, science, and nationalism and the accountability of those who commit unspeakably abominable acts in the name of these institutions and belief systems.

The imperialism at the center of the film (and, by proxy, the Imperial Japanese war effort itself) reflects both Karl Marx’s theory of historical materialism and Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno’s concept of the inhuman consequences of “instrumental reason.” The stratified bureaucracy of Unit 731 and its out of control technocratic positivism creates an atmosphere that rather than enlightening and empowering the oppressed victims of the war, further dominates and exploits them. The ideological tools and practices of fascism and its accompanying military-medical-scientific classes are shown to hide and grow behind the supposed objective “humanistic” practices of science and medicine. With the suppression of ethics, morality, and responsibility, irrational terror can be justified through the use of seemingly rational and logical means.

The title of the film is very evocative and calls to mind the Japanese flag, but also that there were real “men” behind these atrocities. These men try to conceal themselves behind the flag, hiding behind an ideology that fueled the war and its treatment of the Chinese. Mou shows us that ideology didn’t tear the skin off people’s arms, blow out their intestines in hyperbaric chambers, or inject infectious diseases into their bodies; real human beings did these things to their fellow human beings. Ideology didn’t fall from the sky, fully formed, waiting to be discovered by innocent, wide-eyed human beings, nor is it an autonomous independent force with its own agency. A popular justification of Nazi and Japanese war criminals was that they were just following orders, and that they were brainwashed by nationalism and propaganda. Men Behind the Sun rips away this pretext to display the full range of barbarism that needs only a little prodding from authority figures and political ideologues. Belief systems fueled by nationalism and science give men a license to kill, mutilate, and torment without the threat of guilt, morality, or conscience; the members of Unit 731 were primed and ready to go.

The film opens with the quote “Friendship is friendship; history is history,” suggesting that compassion and human relationships have nothing to do with the making of history. History is merciless and inhumane as those who compile the events that compose the narrative of history are more concerned with quantitative statistics and faceless multitudes, large scale occurrences that dwarf individuals and their motivations, deeds, and tragedies. It is humanity in the abstract that is documented, the objective chronicling of wars and disasters driven by political, social, economic, religious, and technological forces that are beyond the individual’s control. The individual may be forgotten, but it is the ideals and ideologies that are more significant: which ones conquered and which were defeated?

Humanitarian concerns are swept into the dustbin of history, with all the other failed accomplishments of the losing side. Men Behind the Sun displays how cheap an individual’s life really can be to those who willingly accept inhuman ideologies and principles that dismiss the humanist notion that human life is of the greatest value. Political beliefs turn individuals into enemies and enemies into victims, victims that will be soon forgotten in the grand sweep of historical discourse. The young soldiers who are portrayed as naïve and idealistic at the beginning of the film are shocked by how callous their superiors are and how unfeeling they are encouraged to be. The young men even stage a mini revolt against their commanding officer when they realize a Chinese boy they have befriended has been murdered in the name of science and the Japanese cause. By the end of the film, however, these young recruits have become not only jaded, but permanently dead inside: their compassion and empathy die alongside those who are subjected to torture in the name of the Emperor. Friendship is for the weak, the sick, the disposable.

In Men Behind the Sun, history is for the cold, the cruel, the dehumanized, those who are willing to sacrifice their own humanity (and the lives of other humans) to satiate their own selfish appetites for power. It is often said that history is written by the victors, and the film shows that those who make history aren’t always noble heroes; victors can be little more than inhuman, sadistic cowards hiding behind political ideology and a facade of “selfless” nationalism. The struggle between the oppressed prisoners (who have committed no crime except for being on the wrong side of an imperialist war) and the oppressive military-scientific hierarchy play out Marx’s proletariat/bourgeoise struggle in miniature: as the Japanese death factory needs resources to fight its war of conquest and profitability, the prisoners are used, abused, commodified, and then killed to sustain a political and economic situation that profits the few but destroys the masses of humanity.

It is not only history-making political leaders and their fervent believers that can rationalize and commit crimes against humanity. For Mou, the ideologies of science and medicine also provide the validation to exterminate in the name of progress and state. In Unit 731, the scientists, doctors, and professors are more culpable for the crimes committed there than the military are. The scientific facade of objectivity, disinterest, and neutrality crumbles in the face of nationalism, as research, empiricism, and the scientific method underpin the greatest crimes of World War Two’s fascist regimes. Rather than being a check on or balance to the irrational fanaticism and jingoistic imperialism of politicians and the military, the scientific and medical communities and institutions actively collaborate with their governments, helping to justify the corresponding ideologies that buttress their policies. The scientific “proof” of biological and racial superiority made Unit 731 and the Holocaust possible. In Men Behind the Sun, the doctors have no conscience or ethical boundaries; compassion and mercy are impediments to progress and the Japanese war effort. The Hippocratic Oath withers in the face of power, ego, and control. To the members of Unit 731, dissecting a still living human being is evidence based medical data not an inhumane butchering (some of the experiments and their results were actually published in peer-reviewed Japanese medical and scientific journals).

Many of the experiments performed in Unit 731 had no real medical or scientific worth, but, rather, were exercises of power and dominance: the doctors and scientists could do whatever they wanted with their “Manchurian monkeys,” and so indulged in an orgy of torture and death in the name of furthering science, defeating their enemies, and hardening the resolve of Japan. The scientists and doctors of Unit 731 are portrayed engaging in what Horkheimer and Adorno call “instrumental reason,” a mode of thinking and acting in which people can rationalize their beliefs and actions by utilizing the abstract rather than the specific. Instead of treating people as individuals, instrumental reason sees a generalized humanity who can be categorized and classified according to totalizing types, reducing human beings to broad processes and characteristics. This kind of reason would then be most valued by quantitative researchers who believe by not focusing on the specific or contextual, universal, non-biased knowledge can be discovered.

Hiding behind the rhetorical construct of objectivity allows madness to reign under the guise of detached reason. Human beings become abstractions, numbers, statistics, things to be experimented on, catalogued, and then discarded by those operating in the name of the benefit of the state and scientific innovation. Indeed, the subjects of these sadistic experiments are called “logs,” whose defiled bodies are thrown into an incinerator when they have outlived their usefulness. Each day scientists would fill out reports on how many “logs fell,” and the joke among staff was that they were not a military base but, rather, a “lumber mill.”

Although Japanese ultranationalist militarism would be defeated in 1945, many of Unit 741’s scientists and doctors would go unpunished, scooped up in the U.S.’s Operation Paperclip, recruited to help fight the Communists, validating the work done by these indifferent monsters and absolving them of any and all guilt for the abhorrent crimes they committed. Ironically, those “god-less” Soviet Socialists would be the only country that held members of Unit 731 accountable in war crimes trials in 1949.

Men Behind the Sun has been called a cheap, nauseating exploitation film, and yet the question becomes how can one explore atrocities without showing them? Should one make these crimes and the treatment of victims palatable for delicate or proper sensibilities? Doesn’t the watering down of history and real events do a grave injustice to the victims? Does a diluted accounting of what happened make it possible for it to happen again? In his essay “On Abjection,” New Wave French film director and film critic Jacques Rivette takes to task Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1960 film Kapo (a work that portrays valorous, indomitable life and noble, fearless death in a Nazi concentration camp) by pointing out:

“for so many reasons, all quite easy to understand, total realism — or what serves as realism in cinema — is impossible here; every effort in this direction is necessarily unachieved (that is immoral), every attempt at reenactment or pathetic and grotesque make-up, every traditional approach to ‘spectacle’ partakes in voyeurism and pornography … At the same time everyone unknowingly becomes accustomed to the horror, which little by little is accepted by morality, and will quickly become part of the mental landscape of modern man”

One of the key weapons that the Japanese scientists, military officers, and political leaders utilize in the film is secrecy and silence. By covering up their crimes and encouraging the notion that not speaking about what they have done are forms of loyalty, duty, and strength, not only are the victims of Unit 731 forgotten but they are also denied any voice, justice, or peace. While some might see the haunting memories and lasting psychological problems of the young soldiers who witnessed these crimes and said nothing as just retribution, by not directly confronting the individual and collective traumas of these events and not identifying the who, how, where, what, and why of these atrocities, all those involved are trapped in a stasis of despair and deception.

Men Behind the Sun proves that to expose the heart of darkness one has to enter the heart of darkness and go all the way through it until one comes out the other side, affected, transformed and enlightened. Covering the darkness up or making it more pleasant isn’t going to “fix” history; not facing that dark heart (some darker than others) that we all possess won’t alleviate suffering or bring justice to victims, past, present, or future. Perhaps this is where art trumps history by allowing in the irrationality, the forgotten, the unacceptable, the unspeakable, the evil that humans do fueled by political and scientific ideologies that historians sometimes turn a blind eye. In that case then, Men Behind the Sun is truly necessary but repellent art because it points a monstrous finger directly at the guilty parties.

William Burns is an English professor at Suffolk County Community College. He has published a book of horror criticism A Thrill of Repulsion: Excursions into Horror Culture and has a book Ghost of an Idea: Hauntology, Folk Horror, and the Spectre of Nostalgia coming out through Headpress Books.