By Yanis Iqbal

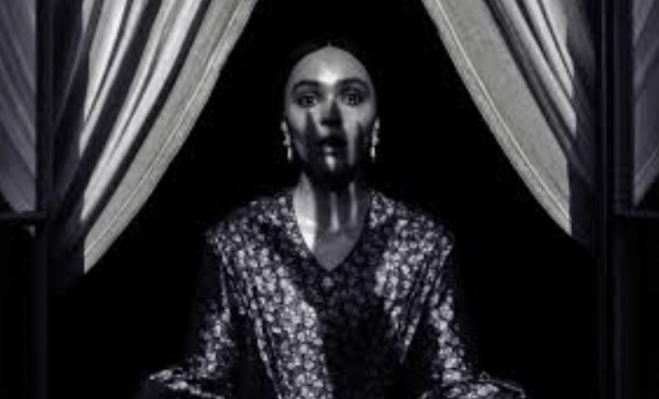

In Nosferatu (2024), Ellen, a young woman unwittingly caught in a supernatural bond with the vampire Count Orlok, becomes both the victim and the savior in a tale of sacrifice and redemption. Her struggle against the dark forces that control her body and mind leads to a self-sacrificial act, where she dies in order to defeat the vampire and save her town from a deadly plague. On the surface, this narrative presents Ellen as an empowered figure – an autonomous individual whose innate supernatural abilities give her the strength to confront evil. As Jenn Adams says, “[Ellen] has willingly given her life to save the man she loves and a city plagued with the vampire’s curse. But not because she is without sin. In fact, it’s because she has command of witchlike powers that she is able to defeat this powerful entity”.

The film does appear to frame Ellen as a liberal subject endowed with supernatural abilities of foresight, hyper-sensitivity, and sacrificial will – all of them making up a mythical destiny. These powers are presented as if they precede society, as if they originate from some internal, mystical source that defines Ellen’s individuality. This framing feeds into a familiar narrative: that of the exceptional individual whose unique gifts are misunderstood, feared, and suppressed by a conservative or ignorant society. In this view, Ellen’s tragedy lies in the world’s inability to recognize or accept her powers. Her clairvoyance and eventual sacrificial act become markers of an autonomous inner strength, something she always possessed and finally chooses to use.

But this liberal world is riven by contradictions. If her powers are truly given, truly supernatural, they should have a clear and coherent path of realization. They should function as stable capacities, leading inevitably to their own fulfillment or expression. Yet the film destabilizes this logic. Ellen’s so-called “powers” are never stable or coherent within the film. Instead, they surface as scattered, ambiguous experiences that she herself struggles to comprehend. In the scene with Von Franz (a Swiss metaphysician and occult scientist), she recalls how, as a child, she “always knew the contents of [her] Christmas gifts,” and knew that her mother would die – fragments of foresight presented not as supernatural triumphs but as haunting, isolating burdens.

The scene between Ellen and Franz does not reveal a woman recalling powers she has always possessed, but rather a subject struggling to narrate a set of experiences whose meaning has never been stable. Ellen’s “powers”- her ability to foresee, to sense presences, to intuit events – do not arrive in the script as clearly defined supernatural gifts. They emerge, instead, in a halting, fragmented syntax: “Sometimes it was… it is like a dream”. This linguistic instability is not just a stylistic flourish; it enacts the very condition of what Ellen describes: an experience without settled shape or clarity. Her account wavers between tenses, between memory and ongoing sensation, suggesting that what she’s describing never resolved into a past event; it continues to trouble her, to shape her, to remain unfinished. This lack of temporal clarity mirrors the indeterminacy of what she’s describing: the sensations of knowing, of being found in strange places, of frightening her father. These are not narrated as controlled experiences, but as affective eruptions that have never been given stable meaning.

What she narrates is not a mystical endowment, but a kind of pure potentiality: a set of affective and sensory events without fixed meaning, suspended between memory, dream, and bodily disorientation. The ambiguity of Ellen’s voice is a key detail: though “weak,” she speaks “with ease, without shame,” suggesting not confidence but a kind of emotional detachment, as if she herself does not yet fully understand what she is recounting. Her tone does not assert mastery over her experiences; instead, it conveys a quiet bewilderment, a drifting between registers of memory, dream, and interpretation.

The interplay of shame and calm is also striking. Ellen grows “uneasy” as she speaks of her father’s reaction, of her own loneliness, of being found unclothed. Her language becomes choked with pauses and hesitation (“my body… my flesh… my…) indicating a moment that is both traumatic and erotically charged. Yet she does not break down. The scene stages a delicate contradiction: she performs composure even as her words betray an inner volatility. This composure is not evidence of self-possession, but rather of how thoroughly she has internalized the gaze of others. Her calm does not indicate control over her narrative, but shows how deeply that narrative has been shaped by external shame.

Her strange sensations and dreams are only retrospectively constructed as “powers” through the fearful reactions of her father and the clinical interest of Franz. These reactions produce Ellen’s “difference” as something supernatural, dangerous, or enchanted. In other words, the social meaning of Ellen’s experiences is violently imposed upon her from the outside, transforming a set of diffuse and indeterminate affects into the myth of the mystical woman, the changeling girl, the eroticized seer. The scene’s shifting emotional tones, its oscillations between shame and lucidity, formally enact this process of social inscription. Ellen’s subjectivity emerges not as something repressed, but as something forged through the very mechanisms of misunderstanding and fear.

The origin point is not one of repression, but of construction. The supernatural is not what Ellen has, but what she is made to be. This is where a more structural reading displaces the liberal myth. Ellen’s so-called supernatural abilities do not precede society; they are produced within it, named as “powers” only after they have already been coded as threats, excesses, or symptoms. Her foresight becomes meaningful not because it is ontologically given, but because society needs a name for what it cannot assimilate – female knowledge, unpredictable desire, porous subjectivity. The attribution of power is thus always post-facto, retroactive. Society sees something anomalous in Ellen’s behavior and constructs it as “supernatural,” thereby granting it a meaning that justifies fear and control.

Thus, Ellen’s powers are not supernatural at all. They are pure potentiality, forms of affect, relation, and intensity that exist prior to any fixed identity or function. This potentiality has no inherent meaning; it becomes meaningful only through historical structures that assign it value, danger, or sanctity. In other words, what appears as mystical foresight is in fact a social and libidinal ambiguity that has been retrospectively framed as “power.” The film, whether knowingly or not, exposes this contradiction. It wants to tell the liberal story of a misunderstood heroine with special gifts, but it also stages the impossibility of such a gift ever existing outside the terms set by gendered, historical violence.

Since Ellen’s powers are only a form of potentiality, they can very well be intrinsically ambiguous. In her conversation with Franz, Ellen asserts, “His [Nosferatu’s] pull on me is so terrible, so powerful – yet my spirit cannot be evil as his”. This names contradiction without resolving it. She affirms that she is caught in a violent affective pull, but she refuses to identify with that pull as essence. This is not an assertion of her purity but a recognition that her being is non-coincident with what pulls her. That is: she does not claim to be free from Nosferatu, but insists that her condition of being-pulled does not settle the question of who or what she is.

In this way, Ellen’s honesty lies in her existential non-closure. She does not speak from a place of sovereign self-knowledge. Instead, she affirms that she cannot master the forces acting on her, that her nature is something she has heeded, not possessed or known. This is a materialist ethics: one that treats the subject not as agent of history, but as medium of historical contradiction.

Franz, on the other hand, cannot tolerate this ambiguity. He performs a kind of theological sleight of hand: first he introduces a faculty that “knows evil,” which he treats as both necessary and redemptive. This faculty is supposedly universal – “we must discover evil within ourselves” – but becomes localized in Ellen – “I believe only you have the faculty to redeem us”.

But where does this “faculty” come from? Franz does not ground it historically, materially, or even psychologically. Instead, he re-inscribes it back into Ellen’s “nature.” When she says “I need no salvation. I have done no ill but heed my nature,” he answers “Then harken to it.” Here, he performs a conceptual inversion: he makes it seem as though Ellen’s “nature,” a material, ambiguous, structurally determined thing, contains within it a latent directionality toward salvation.

This is crucial. Franz idealizes materiality by attributing to it an intrinsic purpose, a directional logic. In effect, he re-spiritualizes the material. Her “nature” becomes not a contested field, not the result of history or socio-symbolic force, but an already-teleological essence that only needs to be “harkened” to.

This “faculty to redeem” is thus not a capacity in Ellen, but a metaphysical placeholder that Franz projects onto her, displacing her structural ambiguity with moral function. He reifies a process (Ellen’s exposure to contradictory forces) into a property. This move does two things: it denies the structural opacity Ellen testifies to; and it re-legitimates the very moral economy that the scene is threatening to dissolve. Ellen says: I am not evil; but I am not free from what draws me. Franz says: Then your entanglement must itself be the key to salvation. This is bad faith. It turns ambivalence into function, contradiction into vocation.

In contrast to Franz’s idealist logic, Ellen’s position suggests a radically different ontology: not a metaphysical faculty of “knowing evil,” but a being-exposed to historical force that cannot be translated into redemption or resolution. When she says, “I have done no ill but heed my nature,” she names her embeddedness in something larger, a social, historical, and affective network. But she doesn’t claim that this embeddedness can be seen through, known, or turned into clarity. It is opaque. She “heeds” it, but that heeding doesn’t produce salvation, only persistence, perhaps endurance. In this sense, Ellen is not a figure of redemption, but a figure of historical immanence: not a heroine, but a site where contradiction is lived without being transcended.

Philosophically, thus, Franz is a reactionary figure. He wants to reassert the primacy of interior knowledge, of moral teleology, of faculties and souls. Ellen undoes this at a specific moment in her conversation: she is what it means to live under a structural ambiguity that cannot be resolved through the appeal to “knowing evil” or “crucifying” it. Her stillness, her pull, her refusal of salvation, they mark the limits of moral intelligibility.

However, the film keeps erasing Ellen’s refusal of Franz’s theological logic. This is evident in the way her bodily states (possession, desire, revulsion, sacrifice) are narratively employed to suggest both subjection and heroic autonomy, while never allowing her to fully emerge as a historical subject shaped by social determinations. Ellen’s experience of possession and somnambulism is initially defined by a loss of self, a state in which her body is overtaken by demonic forces. As Franz puts it, “she communes now with another realm.” Her subjectivity is evacuated; she becomes a conduit for something beyond human comprehension.

But this changes during her physical encounter with Nosferatu, where she is neither fully possessed nor fully autonomous. Instead, her body becomes hyper-sensitized: “her limbs weightless… her body growing hot… her breath accelerating…”- a state of intensified embodiment. However, at the height of this somatic arousal, the script insists that “she holds herself still” and “she disgusts herself by how drawn she is to him.” This suggests a rational self-regulation that exists simultaneously with and in opposition to the force of bodily attraction. The implication is that even as she is overtaken by animal desire, some rational core of her self, some moral faculty, retains control.

Von Franz’s explanation naturalizes this split by moralizing the body: “Daemonic spirits more easily obsess those whose lower animal functions dominate.” Here, bodily animality is rendered vulnerable to demonic invasion, and rationality is cast as a spiritual counterforce. In fact, Franz, as we have seen earlier, asserts that Ellen’s nature itself contains the power to redeem. The same body that was earlier marked as irrational, vulnerable, and animalistic is now reframed as teleologically guided, capable of orchestrating the vampire’s demise through a deliberate act of self-sacrifice.

This contradiction is central to the liberal feminist logic the film promotes. Ellen is allowed agency, but only within a moral framework that sees her bodily nature as both threat and solution. Her sacrifice – letting Nosferatu feed on her until sunrise – relies on her bodily desirability, her animal magnetism, but it is legitimized as an act of conscious heroism. She becomes the redeemer not by transcending her body but by weaponizing it. Yet this is not genuine empowerment; it is a narrative device that exploits her body to secure communal salvation while denying her historical specificity. Her agency is mythologized, not materialized.

What results is a cyclical logic: her bodily animality results in possession (lack of will), but also enables rational control (willful disgust and restraint), which in turn justifies her ultimate sacrifice. The same animality that subjects her to demonic forces is recoded as a source of salvific power. This slippage between body and mind, between instinct and will, relies on an unexplained emergence of rationality from within the body, a rationality that stands apart from and in judgment of the body itself. This is a textbook case of mind-body dualism, the hallmark of a liberal feminism that wants to preserve the illusion of autonomous choice while denying the socio-structural forces that shape and constrain such choice.

Ellen’s body becomes a screen onto which the film projects contradictory fantasies: she is at once the hysterical medium, the rational moral actor, the erotic lure, and the sacrificial savior. But she is never allowed to be a historical subject. Her actions are mystified through supernatural logic, not explained through material causality. The film thus forecloses any understanding of her as a socially embedded figure, shaped by gendered violence, domestic marginalization, or historical circumstance. Instead, it elevates her to a spiritual plane, where agency becomes a metaphysical quality rather than a historically conditioned capacity. In this way, Nosferatu enacts the ultimate failure of liberal feminism: it produces a heroine who saves the world by transcending her body, even as it never stops exploiting her body to tell its story.

Author bio: Yanis Iqbal (he/they) is studying political science at Aligarh Muslim University, India. He has published over 350 articles on social, political, economic, and cultural issues. He is the author of Education in the Age of Neoliberal Dystopia (Midwestern Marx Publishing Press, 2024) and has a forthcoming book on Palestine and anti-imperialist political philosophy with Iskra Books