By Mahim Lakhani

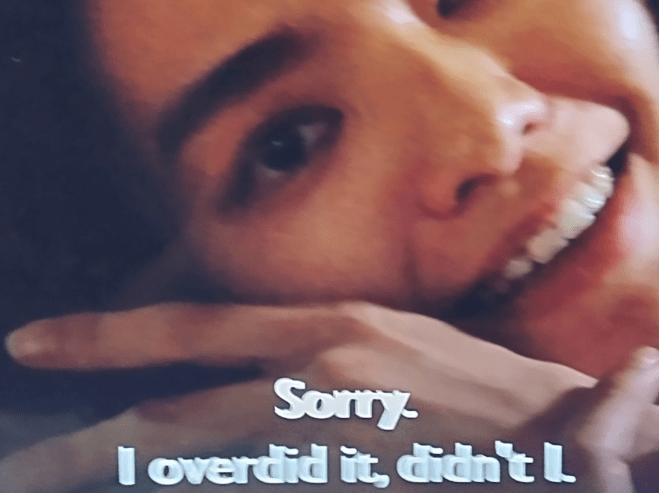

The horrors of the institution of motherhood transcend time. It is an evergreen space offering fears and threats molded and packaged to frighten the living. Kotoko, a 2011 Japanese film directed by Shinya Tsukomoto, shows the travails of motherhood as experienced by Kotoko (played by Cocco). Kotoko is a harried mother disturbed by her own childhood trauma. Persistent and recurring schizophrenic hallucinations make it hard for her to separate reality from delusion. Her desire to fit into the role of a “good mother”, as reified in conventional discourse, triggers her anxiety response, especially while seeing or meeting strangers with her toddler son, Daijiro. Sarah Arnold, in her book “Maternal Horror Film: Melodrama and Motherhood” describes the psychoanalytic context of motherhood in Japan to explain the underpinning of the anxiety haunting our namesake protagonist

…the early mother–child bond structures the infant’s later social relationships. At the heart of the Ajase Complex, and in contrast to the Oedipus Complex, is not only the child’s ambivalence towards the mother but also the mother’s ambivalence towards maternity. However, like the mother of Western psychoanalytic thinking, she must learn to endure (the child’s hostility and resentment) (Arnold 2013, 120)

The Ajase Complex, a counter to Oedipus Complex, was proposed by Japanese psychoanalyst Heisaku Kosawa. He studied the Buddhist legend of Prince Ajase and proposed the primacy of a dyadic maternal model of infantile development in Japan, in opposition to Freud’s triadic union that includes the father. The legend depicts ambivalence that both mother and child feel towards each other. The mother resents the child because it interferes with her own desires; conversely, the child resents its mother when it finds out that she’s not completely devoted to its care. Instead of drifting towards the father, due to this conflict, mother and child engage in a mutual conflict resolution process, culminating in ‘Amae’, a state of mutual dependence where they both forgive each other.

Kotoko shows this conflict: the titular character’s wish to play the ideal mother – personifying virtues like “self-sacrificing”, “nurturing”, “devoted” – while pressing hard against her infanticidal fantasies towards her child. This also corresponds with Laplanche and Pontalis’s concept of phantasy, not as desire, but as the “mise-en-scene” of desire (Laplanche, Pontalis, and Pontalis 1974, 318). The setting, which fills these hallucinations, creates a space to discuss the conflict between Kotoko’s hidden resentment and conscious moral and social obligations she feels subjected to. The desire to avoid anxieties associated with motherhood is narrativized through her hallucinations, where she eventually loses her son and no longer needs to take care of him.

Takie Sugiyama Lebra’s book Japanese Women: Constraint and Fulfillment explains how a mother’s self-identity is embedded in her child: “For many Japanese mothers, the child represents her Ikagai (life’s worth) above anything else”(Lebra 1984). Likewise, the outcomes of the child’s life are always attributed to the devotion or neglect of the mother. What constitutes “motherhood” in a society is determined by ever changing social relations and material conditions and is always different from the experience of mothering.

Kotoko opens with the protagonist feeling the crushing and debilitating force of this invisible societal expectation, in which self-sacrifice is a mandated virtue. She is overwhelmed by the burden of responsibilities that come with caring for a child and working a job. This is poignantly demonstrated by the scene when Kotoko is cooking in the kitchen with Daijiro in her arms. She is caught between giving her son undivided attention and cooking to nourish herself. Ultimately, she is unable to do either, and we hear her internal monologue: “I wonder how other mothers do this.” Kotoko struggles to fulfill the idealised role of the “ever-devoted, never-angry, and always-loving” mother at the cost of her personal sanity.

The culmination of this conflict, over the course of the film, leads to a depiction of motherhood that breaks beyond the “good/bad” binary. As Sarah Arnold notes: “…that the Bad Mother is not only a product of the patriarchal imaginary, or a representative of the nightmare unconscious, but also a transgressive figure who resists conformity and assimilation.” (2013, 69)

I argue that Kotoko is a feminist horror film rearticulating motherhood within the symbolic patriarchal universe, wherein Kotoko’s maternal-centered subjectivity creates a new discourse outside the binary depiction of “Good” and “Bad” mothers in horror films.

Kotoko: The Abject

In “Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection”, Julia Kristeva defines the abject, as that which does not “respect borders, positions, rules” (Kristeva 1982)- that which disturbs identity, system, and order. Kotoko toes the border between sanity and madness. Her inability to differentiate between the real and the phantasm, and her simultaneous perception of both, threatens our (the audience’s) lucidity. We see the world through her experience and believe what she sees.

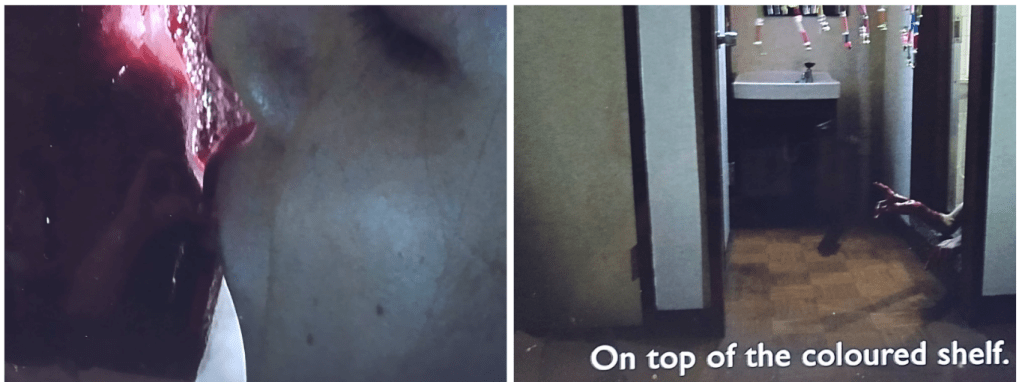

She further threatens normalcy by her acts of self-harm. Her body is a battleground, containing marks of her conflicts with herself. We see her honing the blade of what looks like a pencil sharpening knife, followed by her cutting her wrists. Crimson blood blankets her arms. Barbara Creed in her work, “The Monstrous Feminine: Film, Feminism, and Psychoanalysis”, writes: “Most horror films also construct a border between what Kristeva refers to as ‘the clean and proper body’ and the abject body, or the body which has lost its form and integrity. The fully symbolic body must bear no indication of its debt to nature.”

Images of Kotoko covered in blood make her look threatening and unnerving; she crosses the boundaries of sanity and self-preservation, thereby threatening the symbolic order. The aftermath of this corporeal damage is visible throughout the film on her arms, serving as a reminder to the audience of her “othering.”

There is another factor contributing to Kotoko’s abjection: vampiric imagery. Kotoko meets Tanaka for the first time when she’s on a bus to meet Daijiro. Kotoko is singing quietly to herself, an act that grounds her in reality. Tanaka is riveted by her singing. He eventually finds where she lives and goes to see her. The first time Kotoko displaces her pain onto him – that is, causes him bodily harm in place of harming herself – she shows a desire to taste his blood. It’s only shown once in the film, but is very explicit. We also see her long fingers covered in blood in some of the self-harm scenes. Both of these bear a striking resemblance to the motifs and images seen in vampire films.

Kotoko’s actions of self-harm and episodes of the delusions within the symbolic represent her sadness; a feeling she never articulates with words. She uses a blade on her arms – the very arms that she’s worried are frail and not strong enough to hold Daijiro – again showing the conflict in her psyche that wants to destroy the part of her she feels is essential for Daijiro’s survival.

Irreducible to its verbal expressions, Kotoko’s heightened emotion in some scenes after cutting herself and being covered in blood serves as moments of protest that trouble the ideological norms under which motherhood is produced. To summarize, Kotoko’s psychotic delusions combined with her self-harm, bloodlust, persistent death drive, and inability to integrate with the symbolic order, all participate in her abjection.

Kotoko: The Mother and The Child

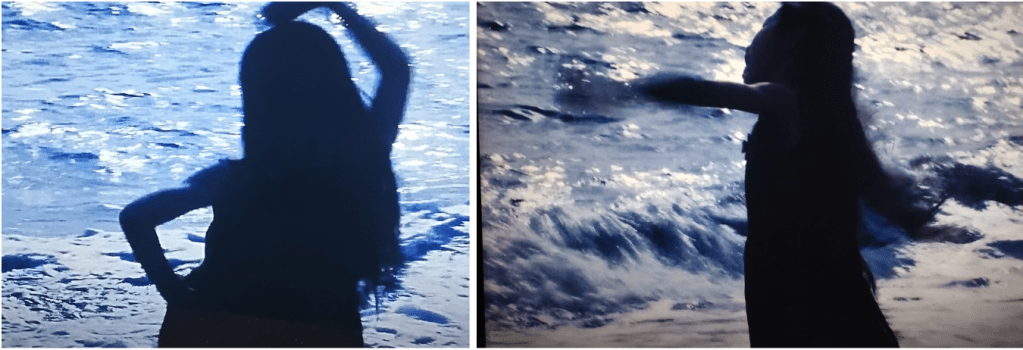

Kotoko opens with a hazy silhouette of a girl elegantly dancing on a beach. We can presume this is a memory of Kotoko from her childhood. Her dance is startlingly interrupted by a woman’s screams. The ocean’s white noise, which earlier harmonized with the flute and glockenspiel, now acts as a blanket to cover the bellows of a woman in danger. The audience is left to look at the waves through a shaky camera as we hear screams. We never see what exactly transpired or who is left shrieking; we leave the scene unsure of what happened, unsettled and filled with the anxiety of not knowing what we witnessed. This narrative tool serves as a leitmotif for scenes depicting Kotoko’s hallucinations. This uncertainty, experienced by us, puts us in the same category as the protagonist, who exhibits a kind of inferential confusion in life situations. We could also surmise that Kotoko’s childhood involved a traumatic incident where her life, or the life of a family member, was imperiled by an unforeseen situation, which could serve as the raison d’être of Kotoko’s heightened anxiety around Daijiro’s safety.

After the film’s title card fades to black, we see a glassy-eyed Kotoko underlining words on a piece of paper. She lifts her gaze to see her son playing with a stranger. Her expressions change abruptly as she moves her eyes to see a “double” of this stranger staring angrily at her. The confusion intensifies as she sees Daijiro still playing with the man. Finally, she cowers in fear as the chimeric double attacks her, only to feel relief from its disappearance since it was not real. The same situation unfolds in different ways multiple times in the film.

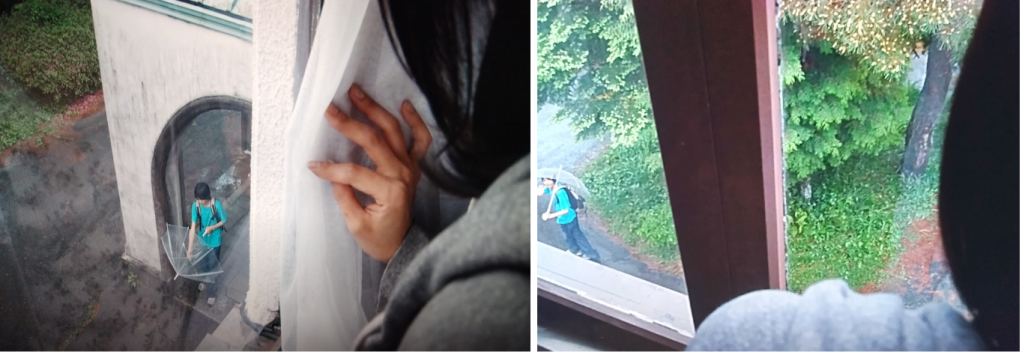

After her first exchange with Tanaka, she dreams he hurts her. She is transported back to the beach, and a rapid succession of cuts shows a girl and beach scenes. The dream culminates with Tanaka assaulting her and suffocating her using a plastic bag placed over her bloodied face. This could be another indicator of Kotoko’s backstory as mentioned earlier – the implication being that under the duress of past trauma and the crushing responsibilities of motherhood, Kotoko is unable to distinguish between her internal imaginings and external reality. The situation worsens to such an extent that Daijiro’s custody is handed over to her sister because she is suspected of child neglect and abuse.

As Kotoko sinks deeper into madness over the course of the film, these delusions don’t even need a real person to activate; a mere image on a television screen suffices. This “doubling” that Kotoko experiences is symbolic of her subliminal conflict with her “mothering self”, which is unable to nurture her child and fulfill her fantasy of living idealised motherhood.

There is no mention of or reference to Daijiro’s father throughout the film. Kotoko is shown handling the pressures of work and motherhood alone. She wants to be a good mother; she wants to be happy, as is evident when she tells her sister, “I’m going to be happy and surprise those who left me – all of those who deserted me. I’m going to be so happy. And surprise them all.”

Renowned cultural theorist Laurent Berlant, in her book “Cruel Optimism”, defines the eponymous concept as the paradox in which working towards fulfilling a conscious or unconscious attachment to certain hopes and aspirations, while giving comfort and a sense of possibility, also proves to be the main detriment to self-actualization and flourishing. This concept would be a fitting way to describe Kotoko’s attachment to motherhood: her desire to feel fulfilled by being a good mother is what’s standing in the way of her happiness.

The anxieties of motherhood are assuaged when familial support systems are present, as seen during Kotoko’s visits to Daijiro while he’s living with her sister. During these visits, Kotoko sits alone by the water, experiencing moments of happiness because the help provided to her by her sister’s family makes her feel unburdened by the responsibilities of motherhood. Without the presence of social or familial support structures, motherhood in isolation emerges as a more pervasive and generalized ailment of society, inflicting trauma not just on Kotoko but on mothers generally.

Kotoko the Lover & Tanaka the Virtuous Mother

As mentioned earlier, the phenomenon of “doubling” has manifold expressions in the film. Apart from seeing physical “doubles”, and in reference to her dual feelings about motherhood, another way this “doubling” manifests in the film is through the question of Tanaka’s materiality. Kotoko is an unreliable narrator because we, as the audience, are never certain if what we see is real or an outgrowth of her imaginings. Some characters and situations in the film inhabit a kind of double space that makes it hard to determine the veracity of their materiality. Tanaka is one such character. There is no way to tell how much of him is “real” within the story.

After seeing him briefly on the bus, Tanaka’s face shows up in a television segment that Kotoko watches, depicting him as an accomplished writer, thus leading the audience to believe there is a degree of realness to him. Kotoko sees him at her home, goes out on a date with him, and takes him with her to her sister’s home. However, his exit from the film brings his materiality back into question. When Kotoko finds out that she has regained Daijiro’s custody, she is ecstatic and walks into his room to give him the good news. She is surprised that not only is he not there, but his belongings, furniture, and books are all gone as well. Alarmed by this, she walks into another room to find him standing there along with his books and furniture. “You scared me. You moved everything into this room,” she says to him, looking relieved. The next cut shows an empty room with Kotoko standing alone, leaving us wondering if he was even in the room, or even in her life. We never see Tanaka talking to anyone else in the film. He might as well have been a corporeal manifestation of desires within Kotoko’s psychic space. He exists in this double space, which is both real and imaginary.

Kotoko’s need for Tanaka could be caused by her desire for her own family after she visits her sister. There is a scene that shows Kotoko’s exasperation upon looking at the “Father’s class visit day” sign at Daijiro’s daycare after Tanaka is gone from her life. Her need for a father figure, triggered by seeing her sister’s partner (and her family) and desiring a familial unit that could help her raise Daijiro, could serve as an emotional trigger for her desire to find (or invent) a partner for herself.

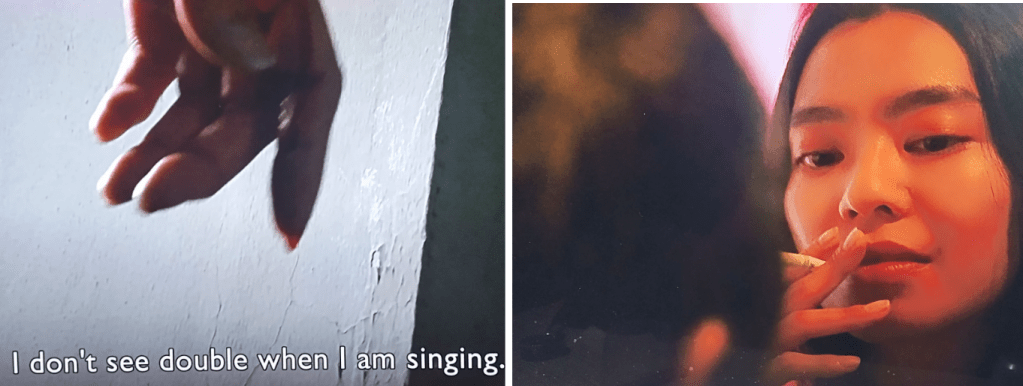

Kotoko says she doesn’t see double when she sings. Singing eradicates her anxieties and gives her a fleeting sense of ecstatic satisfaction. She also doesn’t see double when she’s out on a couple of dates in the film. In a stark reversal of power, Kotoko is phallicized when she meets men on these dates. She seldom speaks and is mostly lost in her thoughts while smoking cigarettes. She shows no fear of these strangers, and does not perform the affective and communicative labour with which women are so often burdened in social situations. She’s uninterested and aloof, knowing that she’s the object of desire nonetheless.

Tanaka persists and pursues her; he has extrasensory ways of knowing when she’s about to cause self-harm and shows up to tend to her wounds. He carries the burden of her pain and offers his body and attention for the restoration of her sanity. In contradistinction to her initial dream, Tanaka is the epitome of love and care. At one point, he offers to stop writing professionally in order to love her full time, which is not an uncommon demand made of new mothers. Kotoko is his Ikagai! He loves her selflessly, with devotion and dedication, just as mothers are expected to love their children. In one scene, we see his hands tied with an electrical wire while a merry-looking Kotoko dances in front of him. He becomes the recipient of the deliberate harm Kotoko would have otherwise inflicted on herself. He prioritizes her needs regardless of his suffering and endures the pain she bestows upon him silently, only to say, “I’m all right”, and that he can take more pain. He loves her the way she wished she loved Daijiro. His self-sacrificing care and complete dedication to her, combined with the viciousness she inflicts on his body, are symbolic of what Kotoko feels about motherhood and the wounds that one has to endure in that role. In Tanaka, she found the ideal, virtuous mother, who only existed to help and heal her.

The extreme brutality of Kotoko’s self-harm and Tanaka’s disfigurement borders on the grotesque – this is in line with the emotional realism embodied in the physicality of characters in other Tsukamoto movies like Tokyo Fist. In Kotoko, however, the wounds are not emblems of exploration, transformation, or even a release of explosive angst leading the character to experience jouissance. Instead, they represent the desperation and isolation mothers experience, dealt with as a last-ditch Hail Mary of sorts – an attempt to experience the living force of the body by a psyche weary of life. This is another instance of “doubling” shown in the film: Kotoko’s wish to feel alive while being fatigued, jaded, and exhausted with life.

Kotoko the Repressed Filicidal Parent

Upon receiving the news that Daijiro will return to Kotoko’s custody, Tanaka vanishes from Kotoko’s life. When she is taking care of Daijiro alone again, her subconscious conflict worsens and manifests in latent murderous phantasies. The finale of these breakdowns starts with her watching a story on television covering a warzone/area of conflict, where an armed man kills a news reporter. Scared by this, she tries to switch the television off, but her futile attempts end with the clip replaying over and over again. Feeling spooked by the situation, she goes to check on Daijiro, only to “see” him being attacked and killed by the very armed man she saw on TV. After Kotoko snaps out of her delusion, her paranoia convinces her that filicide is the only option to save Daijiro from the unpredictable dangers of this world. Rather than being unable to protect him and becoming a bad mother, she believes she will let him go gently and with dignity, by her own hands. A small television set announcing stories of violence is always enough to trigger her anxiety.

In a stark reversal of the usage of this trope by filmmakers like Michael Haneke, who uses news segments (and television shows) to illustrate how accustomed and immune society has become to the violence seen at a distance, Shinya Tsukamoto shows the intense impact that viewership via a screen has on a new mother unsure of her competence and sanity. The repression caused by accepting conventional mothering duties warps her hallucinations so much that instead of addressing the source of her misery, she has to conjure up a roundabout way of annihilating it, leading her to the conclusion that she’s unfit to live in society.

Kotoko : The Ending

Kotoko takes the final word from her obligations of motherhood, which tell her that her pathology makes her unfit to be a member of society. Her punishment is self-inflicted. It’s noteworthy that throughout the film, apart from some brief, suspicious looks given to her by the social worker she meets early on, no other character blames Kotoko for her inability to be a “conventional” mother. This includes her sister and sister’s family, Tanaka, and even the random strangers she attacks, bolstering the argument that Kotoko’s narrative is matricentric – it relays association for the audience solely through her perspective.

The film ends on a more liberating note compared to most other maternal horror films like Carrie and The Others. Kotoko is seen dancing alone in the rain elegantly – and one could even say joyfully and without care – even though she’s in a mental asylum segregated from the world. Kotoko’s madness liberates her from the afflictions that motherhood brought along. As Sarah Arnold notes, while discussing gynocentric interpretation of “Maternal Horror” films :

The horror film, rather than being a site which only perpetuates an ideology of the monstrous mother, provides a terrain where, at times, alternative maternal discourses can be suggested. While the Good Mother maternal horror may encourage identification with the maternal figure, the spectator may identify with her sacrifice, her pathos and her loss. Identification with sacrifice, then, validate the subordinated position of the maternal within patriarchy. In contrast, the Bad Mother horrors, when they do offer increased maternal perspective, may encourage identification with the mother’s transgression (in other words, identification with her rejection of essential motherhood). Identification with transgression questions this very subordination. (2013, 71).

Kotoko’s ending, with her dancing enraptured in the rain, suggests that the film, instead of chastising her for her failure to accomplish the patriarchally circumscribed role of a “nurturing mother”, rearticulates her position outside the preconditions for happiness accorded to her at the beginning of the film. In this way, the film’s conclusion acts as a sort of antithesis of The Shawshank Redemption, where Kotoko is happy in her self-imposed exile within the walls of her mind.

The conflict of motherhood doesn’t leave her completely, as we see a teenage Daijiro visiting her in the asylum. Unlike Tanaka, whose exit was sudden and confusing for the audience, we can guess that Daijiro is real and not a concoction of Kotoko’s mind. This is because the scene of his exit from the asylum has subtle affirmations of his corporeality, including him making an origami crane for her and making the familiar, and familial, farewell gesture Kotoko uses when she goes to visit him at her sister’s home. Kotoko’s exit from the symbolic order, where her motherhood and waged office work defined the honour of her existence, opens up a new space for her to experience the joy of being an absent mother who can delight in the early recreations that once delighted her: singing and dancing for herself.

In Julia Kristeva’s words in ‘Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection’, “It follows that jouissance alone causes the abject to exist as such. One does not know it, one does not desire it, one joys in it [on en jouit]. Violently and painfully. A pas-sion” (Kristeva 1982, 7) .

For me, Kotoko’s madness does not need a somatogenic or psychogenic cause. Her pain is symptomatic of a generalized malaise of omnipresent violence and social death in our world. A world where living everyday is generally and mostly painful. Mental health issues affect us all – well, at least most of us. Even the lucky ones, who are able to get help from medication and behavioural health services, are never completely immune from their anguish. This anguish is not created by our minds, but comes to us from the world outside. So, for those of us who can always see our worst possible self around the corner – not as a threat waiting to jump us but as a fellow traveler who knows how to keep its distance while journeying together – Kotoko’s ending serves as a positive affirmation: that there are no prefigured conclusions to our journey. A happy coda is still possible after a violent ending. We can’t always reconcile the world inside with what we see outside, and it’s ok to exist and struggle through the pleasureless drive that makes us abject but also links our desire to have a world unlike the one we have.

Author Bio: Mahim is, apart from being an expendable prole at his day job, a below-average communist filmmaker and an aspiring film critic living in the Pacific Northwest. He’s a member of the Puget Sound Communist Caucus of the DSA, the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC Seattle), and the Red May organizing collective.