By Aya Anzouk

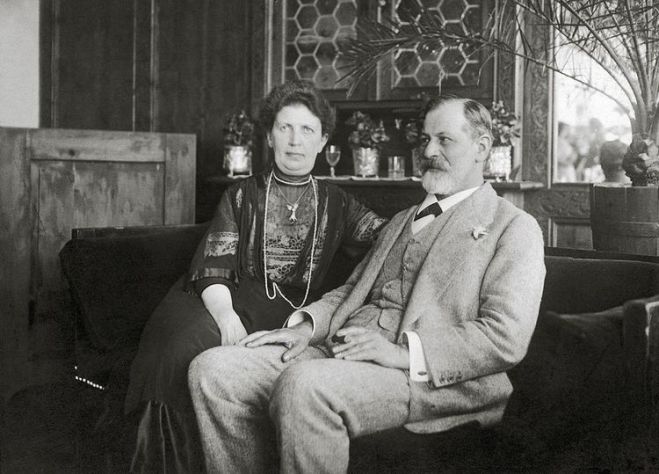

It is virtually impossible to conceive of Sigmund Freud without also considering the manner in which his scholarly contributions have been scrutinized, reinterpreted, and rejected by feminist thinkers and theorists. Although a lot of feminist discourse has employed psychoanalysis to some degree, many feminist scholars have been unable to look past the sexism and the phallocentrism in its founding father’s unscientific science. Either way, one can easily remark the tension between the Freudian doctrine and the mainstream feminist discourse; a conflict which has been both persistent and productive. One of the numerous grievances that most individuals recall is Freud’s theory of ‘penis envy,’ which some argue, is founded on misogynistic and heteronormative perspectives and appears to deliberately overlook the oppressive structures that subject women to violence and discrimination.

Both Freud and feminism sought to decipher the feminine mystique, which remains today a heated topic of discussion within the political and academic spheres. To French philosopher and feminist thinker Simone De Bouvoir, the state of being a woman is not a biological destiny, instead, it is a construct that she develops through her accumulated life experiences and the societal ideals that govern her existence. “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” she proclaimed (Beauvoir, S. d., 2015). The radical feminist movement in the US rejected Freud on the basis that psychoanalysis has dealt with femininity as a problem, whereas the movement in England during the 1970s began drawing from the works of Freud and Marx in order to understand the role of unconscious processes within the individual and the collective psyche in the construction of patriarchal systems (Alexander, S., 1991).

Many years later, various theorists would produce hard-hitting oeuvres about ‘the non-gender’ as well as the performative nature of both masculinity and femininity in the traditional sense. Pioneers of feminist psychoanalysis have endeavored to challenge conventional Freudian concepts by proposing more fluid and adaptable conceptualizations of identity and sexuality, contrasting with Freud’s Oedipus complex, which is predicated on prohibition and scarcity. Not only did Freud’s conceptualization of femininity reduce it to a frustrated desire for masculinity, but it also took away from what many women would consider subjective narratives on female desire and sexuality. Conveniently, Freud’s sexist philosophy was later echoed in classic literature and media, therefore facilitating the creation of a cultural framework in which the female body became an object through which men can affirm the significance of their pleasure, vigor, and virility.

Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel “Lolita” is the ultimate manifestation of the hypersexualization of the female body in culture; while the perpetrator of a grave ethical violation is able to voice his perverted fantasies about a female child, Dolores, who is at the center of his erotic obsession, is denied a say in the matter. Her body is rendered a passive surface onto which this twisted unreliable narrator can project all of his depraved fantasies. The presence of Freudian themes in the novel is undeniable, and while the original work is often interpreted by scholars as a satirical take on psychoanalysis, contemporary media has consistently failed to reproduce the critical lens of Nabokov’s original work. On the contrary, Hollywood film adaptations of the novel have chosen to undermine the important element of critical commentary, creating instead an aestheticized image of a predatory relationship. Consequently, Lolita assumes the role of a seductress when, in reality, she is a victim. Many more female characters in literature and media have been stripped of any autonomy, their personhood reduced to the abrupt whims of male protagonists, further showcasing the lasting effects of Freud’s theories on culture. But while Western feminist critique was influential in exposing inherent patriarchal biases in Freud’s work, it has also committed the grave error of confining its intellectual inquiry within a Eurocentric framework, thus failing to account for or even recognize the importance of the grievances expressed by Global South feminists.

The Coloniality of Psychoanalytic Knowledge and its Critique

In the process of reclaiming the female experience from the influence of Freud’s theories, several feminist scholars whose work was intended to deconstruct misogynistic myths about women inadvertently contributed to the creation of an even more pervasive myth: the myth of ‘universalism’. Through the erasure of the particularities of postcolonial Global South contexts, Western feminist critique of psychoanalysis fails in this regard to portray the lived realities of women whose struggles ensue from the psychic imprint of colonial violence.

Chandra Talpade Mohanty (1988), one of the most prominent critics of Western feminist discourse, argues that much of the scholarship on feminism in relation to the Global South exhibits a tendency toward white saviorism, grounded in a false and monolithic image of the helpless “Third World woman” in constant need of rescue. This stereotyping of women from the Global South deliberately overlooks their valiant efforts to transcend rigid social norms and patriarchal constraints, particularly considering the numerous barriers and obstacles that make it more difficult to overcome these challenges. Additionally, feminist critiques of Freud’s theories tend to overlook the projection of his concepts into cultures that vastly differ from his own.

Much ink has been spilt on Freud’s repeated references to castration as a metaphor for the repression of the drive for incest and/or murder. However, upon further contemplation, I found myself thinking of a more pertinent comparison: the distinction between individuals who possess substantial wealth and influence and those who lack such advantages. This especially applies to working class men who, while they rejoice in thea power given to them by a patriarchal system, are also victimized and marginalized by a capitalist world order which places them beneath the filthy rich men who look down on them. They feel a deep sense of shame about their socioeconomic status and lack of resources, and when other factors like attractiveness and good character fail to make up for their financial shortcomings, they resort to showing off their patriarchal role(s) within the family unit. From domestic abuse to creating a local ‘mini dictatorship’ within the home, these men attempt to rid themselves of the castrating sensation of financial insecurity by orchestrating a powerplay in an environment where they have no superior to punish them for their violence and aggression.

Frederiech Engels (1884) has extensively explored the subject of the family unit and its crucial role in sustaining capitalist order, yet there has been little to no talk about the root of male violence within the family unit in psychoanalysis compared to its exploration in other disciplines like sociology and psychology. Think of the male experience, not as a juxtaposition of the female one, but rather as a body of experiences and narratives which often carry within them severe contradictions. Just like women and girls share many trials and tribulations in the midst of a gendered lived experience, so do men, despite them not being as vocal about it. Both genders are respectively confined to extreme ideals of femininity and masculinity, both of which are directly linked to material manifestations of a performative role assigned to individuals as soon as they are born. Women are coerced into dressing for an ever-preying external gaze and presenting themselves as meek and unknowledgeable. Men are told that they can only achieve ultimate masculinity by acquiring enough wealth and power to become God-like figures. These images, while sharply contradicting one another, make for the perfect heteronormative pseudo-traditional family; a submissive obedient woman and a man with enough money and power to “justify” her submissive demeanor.

Frantz Fanon first introduced the idea of symbolic colonial castration through his writings by laying out the landscape of the colonized nation in many of his books. The colonized or the native is unable to achieve any level of power near to that of the colonizer, and therefore finds masculinity unattainable. It is only if and when the native begins deconstructing the colonizer’s conception of masculinity that he can finally create his own. Syeda & Akhtar (2019) speak of colonialism’s emasculating effect on colonized men, which severely contrasts with the social expectations that various cultures place on men. A man who is incapable of defending his honor at all costs is stripped of any value within his family and community. A man who allows another man, and especially a foreign one, to defile his honor loses his position as ‘man of the house’. These are the unwritten rules of belonging that shape personal and collective identity within many cultures. At the height of the colonial order, men in colonized societies were stripped of any power but that assigned to them by their gendered roles as men in patriarchal societies. Colonialism wasn’t much of a threat to patriarchy either, as it invited a new kind of violence as a way for these colonized men who were struggling with pent-up anger and frustration to finally let it out. Feminist anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod has been a key figure in dissecting ‘redirected anger’ in a colonial context, as she argues that colonialism only undermined indigenous male authority in its relation to the state while it remained unaffected within the family unit, therefore leading to unforeseen levels of subjugation and violence against indigenous women. This aggressive world order that claimed to want to liberate colonized women from their oppressive societies only contributed to their subjugation, both by strengthening patriarchal power within their communities and targeting them for their armed and intellectual resistance against colonial domination.

Psychoanalysis seems adamant about enforcing the idea that our early years are marked by intense desires, many of which are curtailed by prohibition (Verboten). While many feminist thinkers have critiqued this framework, I would personally argue that prohibition is an essential element of the human experience. We are typically born into organized communities governed by their own rules and restrictions, and we are urged to follow these norms, often without question, in order to belong to a collective. In doing so, we begin to conceal parts of ourselves in the attempt to merge into a communal identity, sometimes to the point of erasing our individuality, our distinct thoughts, and emotional truths. Cultural context also matters in this sense, as perhaps this does not apply to certain societies in the West where individuality reigns supreme over community, but the same cannot be said about most ethnic groups in the Global South. Prohibition is often a pillar in some cultures with strict belief systems; there is no margin of error, either you submit or you are condemned to living as an outcast. While Western feminists might be unaware of the social dynamics within other cultures, their work often imposes frameworks that are not necessarily applicable across diverse cultural contexts. Additionally, although feminist critique of psychoanalysis seeks to deconstruct some widespread notions in Freud’s theories that are based on androcentrism and heteronormativity, their failure to account for the cultural and geopolitical specifics that within other societies leads them to repeat the same errors.

I posit that the confluence of feminism and psychoanalysis provides us with profound insights into the formation, resistance, and deconstruction of identities, especially as both disciplines seek to unravel and disrupt the familiarity of social norms. We ought to approach this dialogue with a deep understanding of the contexts that shape both individuals’ psyches and collective identities, because with this awareness we might end up unconsciously erasing other narratives and experiences that differ from our own.

Aya Anzouk is a Moroccan writer and undergraduate psychology student at Al Akhawayn University. Her work explores the intersections of psychology, coloniality, and cultural resistance. She has written for Al Mayadeen, Awan, and Al Tanweeri, and the New Arab.

References:

Alexander, S. (1991). Feminist History and Psychoanalysis. History Workshop, 32, 128–133. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4289106

Beauvoir, S. d. (2015). The Second Sex. Vintage Classics.

Engels, F. (1884). Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State.

Abu-Lughod, L. (2013). Do Muslim women need saving? Harvard University Press.

Mohanty, C. T. (1988). Under Western eyes: Feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. Feminist Review, 30(1), 61–88. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.1988.42

Syeda, F., & Akhtar, R. (2019). Colonization as an Emasculating Experience: The Symbolic Castration of the Colonized Men in Pre/Partition Fiction.Pakistan Vision, 20(2), 97-115.