By Jacob Potash

“We are a religiously mad culture, furiously searching for the spirit, but each of us is subject and object of the one quest.”—Harold Bloom, The American Religion[1]

1. Northrop Frye, had he lived to be a Nicki Minaj stan, might have said that her boasts move in four symbolic registers, and that she adopts a specialized vocabulary which allows for an ambiguity at all times regarding which plane of meaning she is on. The four realms—her preferred metaphors for supremacy—are sex, rap, the drug trade, and sports. Frye might say too that it doesn’t matter to formal criticism whether a rapper has ever had sex or dealt drugs, since she is modifying generic tropes that to most listeners will have a primarily non-literal valence. (Words are, “literally,” metaphors.[2]) What matters in her boasting are not specific images, but the giant form underneath of which these tropes are but the shadow: the rapper’s exultant will, delighting in its own protean power.

The opening bars of her 2017 song “Rake It Up” efficiently announce her symbolic territory:

Brought out the pink Lamborghini just to race wit Chyna

Brought the Wraith to China, just to race in China

Lil bad Trini bitch, but she mixed with China

Real thick vagina, smuggle bricks to China[3]

Naturally, Nicki was mocked for rhyming “China” with “China” five times in a row. Why might she have done so? The word acts as a useful control for isolating her intent: she uses one fairly arbitrary word to refer to (1) her friendship with famous TV star Blac Chyna, (2) her wealth, which is such that she can fly to China on a whim and bring multiple luxury sports cars, (3) her mixed-race (African-Asian) ancestry, which tropologically (in the domain of rap) makes her “exotic,” (4) her interest in competitive sports (she’s off to China to participate in a car race), and (5) her drug-dealing prowess (she claims to smuggle bricks of cocaine to China). China. Fame, riches, sex, drugs. Victory. Domination. China.

We can generalize from this example to say that Nicki’s raps are contentless in a narrow sense. What matters is not what she talks about, but how she talks about it, and what matters about the “how” is always that it testifies to her unconditioned power.

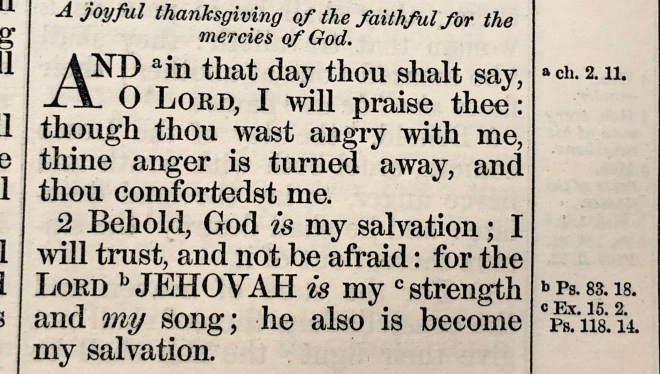

Before you reject such language out of hand as intolerably vulgar—consider a few verses from the Psalms, maybe the most widely recited poems in the history of Western culture:

Happy is the one who seizes your infants and dashes them against the rocks. (137:9)

Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron; thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel. (2:9)

But God shall shoot at them; with an arrow, suddenly shall they be wounded. (64:7)

The dead bodies of thy servants have they given to be meat unto the fowls of the heaven. (79:2)

The register of rap is different from that of the poems to be found in the average issue of The New Yorker. Rough biblical poems, by the same token, were salutary in a late antique setting of Roman and Alexandrian over-refinement. Rap is only as crude as the Bible itself, with its incest, beheadings, eviscerations, slavery, prostitution, forced sodomy, and other instances of brutal subjection and murder.

The Psalms and much of the rest of the Bible should shock us or seem the product of a civilization impossibly distant in time, but the average young person in our country listens to top-40 rap music whose central well of imagery draws from a criminal economy which millions are exposed to and forced into. The musical form took hold during the ’80s, when a young Nicki was growing up in crack-epidemic-era Jamaica, Queens—an epidemic that nearly claimed her own father. The 1980s are remembered as a time of peace and prosperity for certain swaths of white America, presided over by a smiling Reagan. Sex and violence, missing in the lives of suburban teenagers, needed to be supplied from elsewhere, and they were, in the imaginal realm.

What to make of this Christian thing? What to make of this vulgarity thing? What to make of this indomitable will reveling in its own power thing? You’d hope for a concept to unite the chaotic vectors, wouldn’t you?

Come at it obliquely: because of the black church, I would venture many rappers have more familiarity with the King James Bible than all but a few contemporary poets. Nicki’s overt biblical references are frequent (I can think of call-outs to Adam and Eve, Moses and the Red Sea, Alpha and Omega, Jesus on the cross, David and Goliath, the Lion of Judah), but beyond mere surface level allusions, her personality should itself remind one a bit of Yahweh’s, boundless font as both are of self-delight, but also wrath.

It will become clear that Nicki belongs comfortably not in the line of women’s rights crusaders, nor even of innocuously religious pop stars like Justin Bieber—who, thrust at a young age into the spotlight, seems to have resorted to evangelical Christian faith as a sort of coping mechanism—but in the line of televangelists, that quintessentially American cabal of anti-liberal crusaders and media entrepreneurs.

Who is Nicki Minaj? She is not a marginal figure. She at one point held the record for most hits on the US Hot 100 of any female artist in history.[4] Why has her rhetoric achieved popularity within the United States and around the world?

Minaj is a kaleidoscope, not only of contemporary trends in hip-hop, but of the contradictions in our media culture and in contemporary American Christianity. Disarmingly crude, a hardcore but private Christian, and the most popular female rapper of all time, her lyrics and persona form a useful interpretive bridge between the precious world of contemporary poetics and the warfaring kind evidenced in biblical poetry, psaltic and otherwise.

Her ascent was odd. Unlike Bieber, Swift, Timberlake, Spears, Aguilera, Drake, Wayne, Rihanna, Beyoncé, and so many others, she was not a teenybopper star. Her first hit came at 27. Her voice (speaking, rapping, or singing) cannot be called especially pleasant. Her quirky fixations are many and extreme, but whereas journalists in the last decade have mainly gawked at the schizophrenic unpredictability of her looks, accents, alter egos, sound bites, and PR stunts, one might as well patently ignore them, since they are made possible only by the astounding predictability that underlies them.

Behold: the steadfast, assured will to victory of the Christian believer commanded by Jesus to “endure even unto the end.” Older by some years than Obama-style liberalism, this is the same stance, the same godly guarantee that has underwritten the violent, battered, elephantine self-regard of Christian writers like Dante, Milton, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky. Hers is a worldview in tension with the Enlightenment and totally at odds with the political values of many listeners. This is a fact that contemporary criticism has ignored.

Whereas liberalism, in its current state, promotes a combination of private self-indulgence and public (often paralyzing) guilt and renunciation, evangelical Christianity combines private self-denial (essential injunction by Jesus) with relentless, shameless self-promotion and gain—the kind on display in Joel Osteen’s prosperity gospel, or the motivational rhetoric of T.D. Jakes. That Nicki Minaj partakes in this anachronistic cocktail of self-restraint and self-aggrandizement—”God has a plan for your life,” as the megachurch revivalists say—is an untold and not unimportant chapter of our recent past.

2. My aim is not to moralize. Minaj is, like Trump, a representative spirit of our age. I am merely moved to speak by that quirk of our polarization whereby we project menacing trends onto one half of society while magically excusing ourselves.

The feeling I had in 2010 as I heard Nicki for the first time was decidedly not prophetic. She seemed the emblem of all that was outrageous, pornographic, nonsensical, inane, and obnoxious in our culture. I can remember watching the music video to “Stupid Hoe” (which shows her writhe in a leopard-print leotard, blonde wig, and high heels) and feeling sympathy with the tens of thousands of hate comments left below—as on all videos of hers popular enough to cross out of the hip-hop media audience[5].

I think the wished-for prophetic ironist would lament spite and not the artists at whom it is directed; maybe she or he would be charmed to learn that Nicki is not a deranged industry plant, but a Christian who in the ensuing decade has become increasingly comfortable crediting Jesus in her Instagram captions, writing “To God be the glory” on Twitter, thanking her pastor, Lydia, in acceptance speeches, explaining to periodicals that her relationship with the Lord insulates her from scorn, and collaborating with a gospel artist (Tasha Cobbs[6]).

I have kept coming back to Nicki for 10 years and often been unsure why. My fond feelings were threatened by an interview with Elle magazine in 2018 in which she expressed her narrow—claustrophobic?—view of gender and promiscuity. She denounced female rappers who exchanged sexual favors for professional advancement, and took a moment too to cast aspersions on all women who barter sexual acts for gifts. Speaking directly to her female fans, she said, “I’d rather you be called snobby or a bitch or conceited—I’d rather you be called that than easy and a hoe and a slut.”[7] Twitter pounced! And didn’t fail to notice her release the next day of a song called “Rich Sex,” which admonished women not to “let homie fuck unless he got his bands up.” In her song, she taunts an imagined woman: “If you let that broke n**** fuck, we tellin’!”[8] The hypocrisy seemed blatant. She had one message for the interviewer, but used another entirely to push a song that relied on rap commonplaces. Which shouldn’t have been a surprise: only an unusually rigid personal code would allow someone to survive the slings and arrows of a decade or more smack dab in the public eye.

In the same vein, the heralding of Nicki by pop cultural and women’s publications as a feminist hero has always been valid, but at the very least deserves comment. Here is the phantasmagoria of violence with which a 2018 single, “Barbie Tingz,” ends:

Won’t shoot her, but I will gun-butt the bitch

When we say fuck the bitch, dick up the bitch

She was stuck up, so my n***** stuck up the bitch

Still dragging her, so don’t pick up the bitch

Get the combination to the safe, drug the bitch

Know the whole operation, been bugged the bitch[9]

There is overtly feminist rap (Angel Haze, “Bad Woman Good”), but this isn’t that. Nicki is a more useful synecdoche for her genre, because, like Margaret Thatcher, she from the start chose to exaggerate the ruthless and aggressive strains already present in her universe of discourse as a way of balancing against presupposed weaknesses based on sex. (Drake has done a version of the same thing in the other direction.) As her career wears on, her persona has hardened, and certain tropes reappear frequently. Since rap is basically self-referential—a series of boasts meant to make real the clout and largesse by prospectively bragged about—her most relied-upon images should be understood as images for her own creative will, apt qualifiers for which would be: expansionary, victorious, violent, dominant, merciless, playful, exuberant, exultant, and (taking itself to be) divinely sanctioned.

Her public persona does not present much of a foil to her religion-laced lyrics. Take an example. As pressure mounted among fans and advocates to comment on the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting and mourn its mostly gay victims, it was claimed she had tweeted, then quickly deleted, that she believes “what the Bible says, and no one is going to change my mind.”[10]

In October 2020, Nicki and her husband (who has been convicted of manslaughter and rape) welcomed a son whose name has never been revealed. Despite posing for a Virgin Mary-themed pregnancy shoot with the provocateur David LaChapelle[11], her string of post-childbirth rap verses reflects no change in preferred imagery. The religious references persist, but so does the towering, resistless ego. “I holy ground you,” she says to an imagined lover on a 2021 song, making a simple pun.[12]

But how does she ground him? There is no paraphrase possible. She does it by fuckinghim—”I’m bouncing all on the D”—and cursing all small-minded would-be exegetes and competitors. “Fuck you to my enemies.” In an era when only one political party strikes such attitudes and uses such words, they spring up in the oddest places, not least the playlists of tween girls. Out of the mouths of babes…

The last decade has been marked for Minaj by poor publicity about her husband’s legal status[13], intimidation of her husband’s accusers[14], various lawsuits[15], swatting incidents, rumorsd of drug use, feuds, half-baked diss tracks, denunciations of her sister, the child assault conviction of her brother, the murder of her tour manager[16], the indecorum of her fans,[17] and the death of her father in a hit-and-run.[18] She has recently made a habit of demeaning musical superstar colleagues, most of them women, in biblically inflected, seat-of-the-pants eruptions on X. (Gloating over a sexual harassment lawsuit against Megan Thee Stallion, she wrote, among other things: “Touch not my annointed… Vengeance is the Lord’s… We give God the glory & he’s only just begun.”[19]) Nicki as impervious paragon of an early 2010s ecosystem of girlboss-feminist thinkpieces is a fading memory.[20]

The camp poses and two-toned wigs are gone, and what remains is a lawless logic of personal domination that seems inextricable from the fierceness of her faith. Analyses of Minaj as a feminist, or Black feminist, though once legitimate and necessary, may have obscured her unique contribution to the great media whirlpool in which we find ourselves, at present, drowning.

The last word goes, as went the first, to Harold Bloom. Commenting on the legacy of the Cane Ridge revival of 1801, crucial to the Second Great Awakening, he wrote: “To know the American Jesus is a kind of ecstasy to be rivaled only by frontier violence.”

Bloom’s irony is Nicki’s lived reality: in America, religious gnosis and frontier violence are rivals because they are twins.

Jacob Potash is a writer and filmmaker

[1] Bloom, Harold. The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation. Simon & Schuster, 1992.

[2] See The Great Code, Frye’s grand commentary on the Bible. Its thrilling finale rests on a version of the claim that the Bible’s literal meaning is metaphorical. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982.

[3] “Rake It Up” (Yo Gotti ft. Nicki Minaj): https://genius.com/Yo-gotti-rake-it-up-lyrics

[4] Zellner, Xander. “Nicki Minaj Is First Woman to Score 100 Entries on Billboard Hot 100 Chart.” Billboard, 5 Nov. 2018, https://www.billboard.com/music/rb-hip-hop/nicki-minaj-first-woman-100-hot-100-hits-8483256/.

[5] “Stupid Hoe”: https://genius.com/Nicki-minaj-stupid-hoe-lyrics

[6] “Tasha Cobbs Leonard – I’m Getting Ready (Live) ft. Nicki Minaj.” YouTube, uploaded by Tasha Cobbs Leonard, 22 Sept. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-w4Cz5H4oY.

[7] Garcia, Nina. “Nicki Minaj on Cardi B, Eminem, and What She’s Done for Women in Hip-Hop.” ELLE, 10 Oct. 2018, https://www.elle.com/culture/music/a23659229/nicki-minaj-interview-october-2018/.

[8] “Rich Sex” (ft. Lil Wayne): https://genius.com/Nicki-minaj-rich-sex-lyrics

[9] “Barbie Tingz”: https://genius.com/Nicki-minaj-barbie-tingz-lyrics

[10] Hilton, Perez (@ThePerezHilton). “Did @NICKIMINAJ really tweet and then delete…” X, 15 June 2016, [https://x.com/ThePerezHilton/status/743283563664052224]. The authenticity of this alleged tweet is disputed. A screenshot circulated, but its veracity was debated by fans, with many arguing it was fabricated and others insisting they saw it before it was deleted. The controversy itself is indicative of the tensions surrounding her public persona.

[11] “Nicki Minaj Poses As Virgin Mary In Stunning Pregnancy Shoot.” That Grape Juice, 20 July 2020, https://www.thatgrapejuice.net/2020/07/nicki-minaj-poses-virgin-mary-pregnancy-shoot/.

[12] “Holy Ground” (Davido ft. Nicki Minaj): https://genius.com/Davido-holy-ground-lyrics

[13] “Nicki Minaj’s husband Kenneth Petty sentenced for failure to register as sex offender.” CBS News, 6 July 2022, https://www.cbsnews.com/losangeles/news/nicki-minaj-husband-kenneth-petty-sentenced-failure-to-register-sex-offender/.

[14] Patterson, Charmaine. “Nicki Minaj Harassment Lawsuit Voluntarily Dismissed by Husband Kenneth Petty’s Accuser.” PEOPLE, 13 Jan. 2022, https://people.com/music/nicki-minaj-harassment-lawsuit-dropped-by-husband-kenneth-petty-alleged-rape-victim/.

[15] Dillon, Nancy. “Nicki Minaj Sued for Allegedly Ignoring Tour Manager’s Pleas to Stop Husband’s Violent ‘Backstage Attack’.” Rolling Stone, 27 Nov. 2023, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/nicki-minaj-sued-assault-tour-manager-pink-friday-2-tour-1234907996/.

[16]Man Convicted of Killing Nicki Minaj’s Manager.” ABC News, https://abcnews.go.com/US/man-convicted-killing-nicki-minajs-manager/story?id=69304282.

[17] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/09/03/nicki-minajs-dark-bargain-with-her-fans

[18] The Associated Press. “Man sentenced to 1 year in jail for hit-and-run that killed Nicki Minaj’s father.” CBS News, 4 Aug. 2022, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/robert-maraj-nicki-minaj-father-killed-hit-and-run/.

[19] Jackson, Panama. “Nicki Minaj’s rants about Megan Thee Stallion, Jay-Z and Roc Nation, explained.” TheGrio, 9 July 2025, https://thegrio.com/2025/07/09/nicki-minajs-rants-about-megan-thee-stallion-jay-z-and-roc-nation-explained/.

Levine, Daniel S. “Nicki Minaj Resurfaces SZA’s Shady Tweets About Beyoncé, Madonna and Rihanna in Scorching Social Media Tirade.” People, 15 Aug. 2025, https://people.com/nicki-minaj-resurfaces-sza-shady-tweets-about-beyonce-madonna-and-rihanna-in-scorching-social-media-tirade-11773719.

[20] Sarmadi, Camellia. “‘All Girls Are Barbies’: A Feminist Critique of Nicki Minaj’s Barbie Persona.” California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, 2012, https://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1111&context=comssp.

Jackson, John. “Nicki Minaj.” Gender Politics in Rap Music, https://sites.middlebury.edu/genporap/nicki-minaj/.

Davis, Allison P. “The Passion of Nicki Minaj.” The New York Times Magazine, 6 Oct. 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/11/magazine/the-passion-of-nicki-minaj.html.

Abbott Freeman, Ann. “Nicki Minaj inspires young women through her career.” The Villanovan, 9 April 2015, https://villanovan.com/9001/opinion/nicki-minaj-inspires-young-women-through-her-career/.

Hallinan, Chloe. “Nicki Minaj’s Abortion Story: Why We Still Need Feminism.” Women’s Media Center, 15 Jan. 2015, https://womensmediacenter.com/fbomb/why-nicki-minajs-abortion-story-is-so-important.

Gregory, April. “Nicki Minaj: The Flyest Feminist.” STATIC, 31 Oct. 2011, https://stnfrdstatic.wordpress.com/2011/10/31/nicki-minaj-the-flyest-feminist/.

Hope, Kelly. “Nicki Minaj: A Feminist Icon?” Feminist Fatale, 20 March 2015, https://kellyhope1.rssing.com/chan-19450928/article114.html.