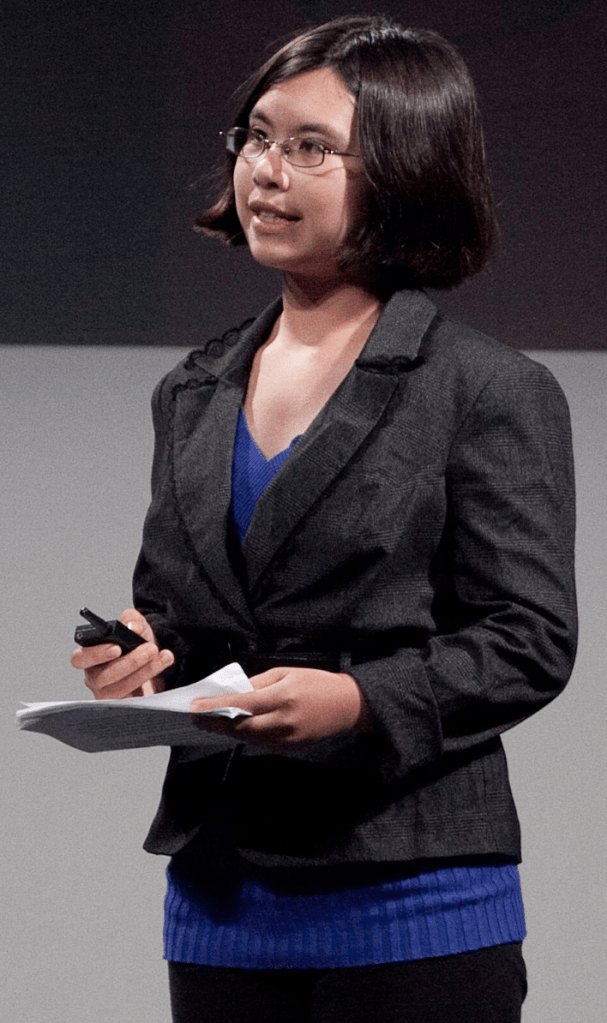

By Adora Svitak

One of my keenest sensory memories from childhood is of having a sound technician’s hand between my waist and my pantyhose. The sound technician was always male, between 20-70, with large hands tufted with hair. Backstage, someone unzipped my dress. On went the microphone pack, this black brick riding the small of my back. The weight tugged down my pantyhose a little. Then the sound technician, sometimes with my mother’s help, would run the wire up. I felt fingers wriggling against my stomach, the windscreen a furry caterpillar dancing up my chest, and the mic’s hard plastic clip on the neckline of my dress. Zipped back up, I’d sit with the stage manager behind the curtain before my call time, watching a sliver of the audience until I heard my cue and sallied into the lights.

I thought about that routine experience, one that I experienced as both quotidian and isolating, because of reading the feminist writer, parent, and teacher Madeline Lane-McKinley’s excellent polemic Solidarity with Children: An Essay Against Adult Supremacy (Haymarket, 2025). Now in my late twenties, it’s been a long time since I’ve given a speech involving sound technicians and stage lights. When I went to college, I largely left behind the professional speaking circuit. Before that, the rhythms of my childhood and adolescence were determined not by eighth-grade graduation, school dances or sports tournaments, but by speaking gigs at schools, idea conferences like TED, and lucrative private events for companies. I was, professionally, a child prodigy.

In my public advocacy for youth — my most famous talk is one I gave as a twelve-year-old called “What Adults Can Learn From Kids” — I shared a goal with Madeline Lane-McKinley. I wanted, and still want, a world in which children could exercise greater autonomy in the service of their flourishing. But my own experiences have also made me cautious of the ways that arguments about youth’s capacity — when you have low expectations, we sink to them, I said at twelve— often liberate youth not to flourish but to work.

Lane-McKinley’s book is careful to walk a line between celebrating children and resisting easy idealization. Early in Solidarity with Children, Lane-McKinley relates an anecdote from her own adolescence, in the fall of 2001. With friends, she skipped school and drove to the University of New Mexico campus in order to participate in a demonstration against the bombing of Afghanistan.

When I told my father about it later that night, he was hardly proud of me. He said that I didn’t understand the complexity of the situation. […] About a decade later, my father apologized for his reaction. He was better than most in this regard, which I don’t fail to appreciate. At the time, though, I remember feeling that he thought I’d been foolish — that I’d acted childishly.

The anecdote is didactic: the kids were right! Yet Lane-McKinley tells readers “childishness” has long been given short shrift, with figures like Lenin, Mao, and Engels blasting others for politics that were too infantile, adventurist, or utopian. In the 60s the New Left flipped that value system on its head, and generations of activists have invoked youth strategically (e.g., Greta Thunberg).

Like Lane-McKinley, I had strong political inclinations as a kid, and bristled at the notion that I should be thought of as less qualified than adults to weigh in on decisions that also impacted me. Solidarity with Children highlights the stakes of violence, exploitation, and policy for children, and the hypocrisies of a world that “may idealize some children” while harming all. Children are caged at borders, made to work in mines, killed with bombs and guns, and deprived of basic choices about their bodies — not allowed to take puberty blockers, forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term — by U.S. law and policy. When some children (e.g., American youth activists) are thought to have more agency, “they are delegated with the impossible task of saving the planet.”

Whose job is it to fight for children? This book resists portraying children as silent victims who require adult protection, and decries calls from the religious right to “save” children imagined to be innocent but vulnerable to perverse adult predation. It is also skeptical of the potential of “inclusion,” which Lane-McKinley calls “a different kind of marginalization.”

It was that convenient, non-boat-rocking logic of inclusion that I experienced the most throughout my childhood and adolescence. I was a token child in rooms of adults. Sometimes, I got lucky and could be with peers, like when I served on a “Youth Advisory Board” for the USA Science and Engineering Festival or partnered with friends and acquaintances to deliver a panel at South by Southwest EDU. I grew cynical early on about how convincing I could be when it was just me on stage. There was a lot that didn’t add up. I gave talks about reforming public school while I was being home-schooled; I gave talks about the problems with determining “merit” through academic achievement while I was trying my best to get into Stanford and Yale. When the occasional skeptical (though unfailingly polite) educator engaged me in Q&A after I’d made an impassioned plea for them to listen to student voices, they sometimes said a version of “Well you’re very precocious, but you’re not the students we deal with.” I always responded that I was a product of the opportunities I had been given. I was a dancing bear and we both knew it.

Other times, questioners took a different tack. They were worried I didn’t have a childhood. I started addressing this concern proactively, saying my mom — contra assumptions based on her ethnicity — was not a “tiger mom,” and that I loved to play outside. I gave a talk at a conference in Texas that I titled “Let Kids Be Kids” to challenge the assumption, which certainly hadn’t been around since time immemorial, that childhood should be a frivolous playland.

Indeed, childhood is a social construct with a history. That’s the message of Lane-McKinley’s second chapter, “Dreams Called Childhood.” French historian Philippe Ariès’ Centuries of Childhood argued children didn’t have a separate sector of society in the Middle Ages, they just mixed with adults after 7. From the sixteenth century onwards European thinkers became interested in the issue of educating children correctly — Montaigne, Locke, Hobbes, Kant, and Wollstonecraft all waxed poetic on molding kids. Lane-McKinley links this project of proper education to class and status distinction: “The literary output of conduct books reflects a broader turn to conceptualizing motherhood, the mother-child relation, and childhood as aspects of an intensifying family ideal of bourgeois society.” Later on, as the category of the adolescent emerged and became popular, psychological discourse about young people’s identity and role confusion lent itself to an understanding of teens as rebellious, troubled, and even monstrous. Lane-McKinley situates present-day skepticism and hostility towards trans youth in that intellectual genealogy. Right now, she suggests, many adults see teenagers and their propensity for change as a threat. Groups like Moms for Liberty and anti-trans “parental rights” movements are scared of shadowy cabals turning their kids gay or trans. Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to draconian limits that seek to curtail their ability to express their own desires, impulses, and values when they don’t accord with their parents’.

In one of my favorite chapters, Lane-McKinley dissects mothering. This is tricky intellectual and political ground for a book about children to traverse. By advancing draconian anti-abortion laws and encouraging surveillance of pregnant people, right-wing U.S. politicians have set up an implicit opposition between (at least “unfit”/suspect) mothers and (potential or real) children. At the same time, some mothers use their position as mothers to weigh in on parental rights discourse and argue for their primacy in making decisions about kids’ access to vaccinations or puberty blockers. This to say: there are situations where mothers and children may be enemies to each other, or at least acting at cross-purposes. Lane-McKinley brings in expansive readings from the Black feminist tradition and Wages for Housework to argue for radically changing what it means to mother. Break away property relations, end motherhood-as-induction-into-secret-cult, and make it possible for everyone to take on the care work for children that we call mothering. That sounds great to me, mostly, in my present childless condition, but then I thought of the bevy of Motherhood Lit that conveys the specialness of this relation. Perhaps no one exemplifies this more than Iris Marion Young in On Female Body Experience. At one point she describes the “soft infidelity” she feels breastfeeding her baby while her husband obliviously naps. It has a pleasurable tone, this exclusivity; it is important, I think, that this is Young’s baby, and that for this sweet moment they form a dyad away from her husband. Certain children are special to certain adults for reasons that are not egalitarian or democratic. We certainly can and should do a lot to change the social construction of care; to make it so gestational parents are not always expected to do so much work; and to give kids lots of options for supportive adults in their lives who aren’t their biological parents. Lane-McKinley’s point on this is eminently reasonable, but I was left wishing for a thick description of a kind of maternal desire and the way it works right now. What are the pleasures, not just pains, that maintain the status quo?

At the end of the day, childhood is made up, and often bad, because adults make it so. It doesn’t have to be. Lane-McKinley states towards the end of the book:

Among children, friendships offer a way to endure this adultist world together, and even to transform it. […] Most of the time, children depend on adults to have access to other children, along with the possibility of friendship and other forms of sociality. Supporting children as they create and nurture friendships is a concrete way for adults to build solidarity.

When I think back on my childhood, I remember phrasing many of the things I wanted as collective desires of kids writ large — for schools that functioned less like factories and gave students the chance to philosophize and dream, for adults who really listened to youth. But my strongest desire, as I toured the world looking like the picture of an empowered youth, was really to feel less alone.

To confess that, I worried, would be giving in to the peanut gallery who claimed I didn’t have a “real” childhood. It would also be showing a lack of gratitude for what I’d been given. I had a microphone, and that was more than most kids. Public speaking was labor that left me wrung out, but it was also an education in how to join the ranks of the “meritorious” elite of the knowledge economy. My saved honoraria paid for college.

There is a version of autonomy and flourishing that doesn’t look like what my childhood was. The choice didn’t have to be between being infantilized and growing up “too fast.” There can be something outside of the neoliberal framework in which she who becomes an entrepreneur of the self earliest wins, while the law plays catch-up (e.g., the Coogan Law on child influencers in CA). Lane-McKinley invites us to imagine a future in which children are neither dismissed nor forced to save the world, a world full of participation in activism, friendship, and solidarity.

Author bio: Adora Svitak is a writer and PhD candidate in the joint program in Sociology and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Yale University. Her writing has appeared in Post45, Apogee, and Kernel, among others; her paper on heteropessimism in literary fiction was published this September in Cultural Sociology.