By Johanna Isaacson |

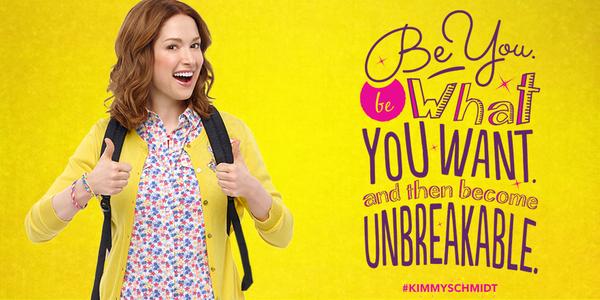

So far in this series on ‘comediennes,’ we have discussed the ways that the current boom in female-centric comedy has failed to break with the patriarchal logics of capital in general. The rise of shows that foreground a “strong” female character making her way in the world, as we see in both recent sitcoms Difficult People and The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, will here help us to map the nature of contemporary commodification and how it relates to the feminization of labor. As Nina Power argues, we are in a moment where labor in general, not just that of women, is feminized by nature of the structural precarity, fragmentation and mobility of contemporary capitalism. The character traits that come to depict the contemporary worker are therein “feminine,” “which is why the pragmatic enthusiastic professional woman is a symbol for the world of work as a whole.” [1] In The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (TUKS) and Difficult People, we see forms of comedy that ultimately recuperate second-wave feminist and gay liberatory structures of feeling, harnessing these forms of representation to an affirmationist reconciliation with feminized labor.

This ascension of a feminine capitalist logic comes in tandem with a stage of commodification in which, as Fredric Jameson argues following Guy Debord, the image rather than the physical product of capitalism becomes “the final form of commodity reification.” [2] In this context, feminism itself becomes a key commodity with the potential to contain and unlock contemporary logics. The appearance of the new brand of comedienne in dominant culture-industry logics reflects and refracts heightened stakes in the commodification of feminism, as the image of female empowerment becomes a key means of naturalizing and maintaining contemporary forms of hierarchy and exploitation.

Obviously, the solution is not to reject feminism. Yet even when it is well intentioned, would-be feminist comedy faces an impasse that sets commodified feminism against anti-feminism, with only something like not-not-feminism or post-post-feminism (something I’ve been calling expressive negation) as a shadowy third option. While neither TUKS nor Difficult People negotiate this impasse particularly well, the staging of these problems in female-oriented comedy is revelatory.

Primarily, these shows model the way that society as a whole now trades in the image of feminism in order to ward off criticism of a rigged game. The reigning mode in these forms of comedy is a form of affirmative identity politics. Both protagonists Kimmy and Julie are presented as coherent personalities whose core forms of interacting with the world entail a kind of authenticity, pluckiness, and fighting spirit.

In TUKS, Kimmy, victim of a 15-year long kidnapping by a self-styled preacher of a doomsday cult, reemerges into the world with only her hunger for experience, her innocence, and the resilience she learned in captivity. The source of humor in this show is premised on a few things: Kimmy’s over-the-top enthusiasm and optimism, her lack of familiarity with the latest technological and cultural innovations, and the excesses and self-objectification of the people around her, especially her wealthy, trophy wife employer and her gay black would-be entertainer roommate. By criticizing her rich employer and showing the struggles of the precariat in the gentrifying city, the comedy, at first glance, forms a situated critique of the construction of class and gender. However, as in 30 Rock, the show resolves with a tacit message affirming the resilience and cleverness of the feminized worker-protagonist, constructing her as a deserving elite who must “lean in.” This idealization of Kimmy’s ability to pull herself up by her emotional bootstraps dissolves or resolves the contradictions brought up in earlier episodes.

TUKS is a show that is knowing in many ways, but utterly unreflective on the history of comedy and its relationship to minstrelsy. The character of Kimmy’s roommate Titus is played in a highly stereotypical key. Titus’s obsession with image culture, vanity, and callowness are the butt of many of the show’s key jokes. At the beginning of the series this is tempered by his status as the cosmopolitan sophisticate, ushering the naïve Kimmy into an unfamiliar world. By the end of the season, however, any tiny kernel of Titus’s sophistication has been dissolved, as we see him in a fully minstrel, abject light, singing, screaming, crying, crawling, and farting on TV, as appalled white people look on with their dignity in tact.

Kimmy, on the other hand, increasingly takes the chaotic affairs of all the characters in hand, including those of her highly stereotypical Chinese boyfriend Dong. In parallel to the Liz Lemon character on 30 Rock, Kimmy serves as the other characters’ manager, keeping their excess in check. Through this, the message is cemented: competent women must “lean in” alone, not expecting any collaboration or communality. They must feign mutuality and maintain a maternal fondness for their subordinates, who they secretly know are to blame for their own lack of success. In 30 Rock, class reconciliation is depicted through the relationship between Liz Lemon and Republican CEO Jack Donaghy. Kimmy Schmidt’s relationship to power is not personified. Rather, the primary coding of her resilience is her conciliatory and managerial relationship to what Mark Fisher calls “capitalist realism,” the notion that there is no alternative to the economic, political and cultural status quo.

By the end of season one, Kimmy is depicted as the only competent character in the show, and, paradoxically, the most cosmopolitan. Back in her home town of Durnsville, she is successfully villainized in court by her kidnapper Reverend Richard Wayne Gary Wayne because of her association with New York City. The message here is that although both New York and small town Dernsville represent different kinds of unfairness and incompetence, in New York Kimmy has managed to achieve independence, something impossible in her small Midwestern hometown.

The lesser of two necessary evils, then, is Kimmy’s choice to “lean in” to demanding cosmopolitan life and take the reigns from less competent hands. In short, the initial critiques laid out in the show turned out to be what Roland Barthes called an inoculation, admitting some evil in an institution in order to deflect awareness of its structural problems. [3] The problem with the system isn’t the system, it’s that strong, feminist women like Kimmy are not in charge. This is the commodification of feminism that shows the imbrication of spectacle and the feminization of labor.

This logic is heightened in Difficult People, a show produced for Hulu, created and written by comedienne Julie Klausner. The series depicts the everyday lives of best friends Julie Kessler and Billy Epstein as they try to succeed in in New York’s entertainment industry. Here the means to commodify feminism is through the full recuperation of camp. Julie’s persona of the brassy pushy narcissistic funny lady with a gay best friend has a long tradition in gay culture. While on one level, camp was always depoliticized, it initially had a relationship to what could be called expressive negation or estrangement, a drawing attention to the constructedness of things. As Susan Sontag initially put it:

Thus, the Camp sensibility is one that is alive to a double sense in which some things can be taken. But this is not the familiar split-level construction of a literal meaning, on the one hand, and a symbolic meaning, on the other. It is the difference, rather, between the thing as meaning something, anything, and the thing as pure artifice. [4]

In the history of gay and feminist liberation, camp humor and sensibility periodically took on overt political stakes, allowing détournement of naturalized gender and sexual roles. In the face of the secrecy, modesty, timidity and shame required by women and gays, larger than life campiness was an assertion of the right to speak and act and the right to construct subversive identities, cobbled out of media stereotypes. This latent political possibility was seen in the Stonewall riots, led by trans women and sex workers and taking place on the day of Judy Garland’s funeral, showing the potentiality for brassiness and camp to develop into militancy.

However, Difficult People shows the full recuperation of this campiness. Julie and Billy are obsessed only with the entertainment industry and their careers in it. There are no ends to their campy behavior other than to reproduce and enter the logic of the media. They are not nice people, and the show foregrounds their meanness as the source of humor. However, like Kimmy Schmidt, their reaction to the context around them, in the end, is elevated as a feminist brand of independence. Their “difficult” meanness and self-absorption is not, finally, horrible. In contrast to the people around them meanness turns to sharpness and sharpness to acuity, making them the realists of the show. Julie’s earnest boyfriend, Arthur, works for public television, and is sidelined as an ineffectual fool. In the end, his form of idealism is feminized, and Julie and Billy are shown to be the most traditionally masculine characters on the show. This elevation of the masculine is underscored by Billy’s disdain for Matthew, his hyper-effeminate coworker. Like TUKS, the series begins with an equal distribution of undesirable and laughable characteristics to all the characters, including the protagonists. However, in the end Julie and Billy are revealed as the smartest kids in the room. This is exemplified in episode five, where they decide to help out Arthur by intervening in his station’s terminally boring fundraiser. To raise funds they stage a mean-spirited roast on the air, raising record-breaking amounts of money, ultimately saving Arthur’s job. Here, it is made clear that their brand of sensibility is a kind of realism that more decorous characters can’t access.

Although Julie and Billy are mean and impractical on the surface, at their core they represent an idealized commodification of feminism that can surf the waves of precarity and media logic to control the discourse in an ultimately fairer way than the more incompetent or complacent people around them. That the protagonist is a “they” stages the way that commodified feminism comes to subsume all other potentially subversive identities, presenting the spectacle of a post-racial, post-heterosexist, pro-feminist world, hiding the deep structures of inequality, in which, as Chris Chen notes:

“Race” has not withered away: rather, it has been reconfigured in the face of austerity measures and an augmented “post-racial” security state which has come into being to manage the ostensible racial threats to the nation posed by black wageless life, Latino immigrant labour, and “Islamic terrorism.” [5]

Julie and Billy exemplify the ideological elision of structural racism and sexism by presenting a spectacular reconciliation. The two characters’ meanness does not extend to each other. In every case they support and echo each other. This plural yet singular identity plays out solipsism as empathy, allowing for a figuration of the new kind of individualism required to facilitate and mitigate the contradictions of feminine labor.

This critique isn’t to say that these shows aren’t funny. To my taste TUKS is funnier than Difficult People, as Tina Fey’s speeded-up just-in-time production of jokes are a consumer item geared to my taste as a literate Gen-Xer while the narrowed range of referents to very contemporary, very popular culture in Difficult People misses my demographic. But the differences in the two shows further demonstrate the entrenchment and flexibility of ideological feminism and the stranglehold it has on supposedly subversive genres.

Read the other installments of this series: I, III, & IV

Works Cited

[1] Power, Nina. One Dimensional Woman. The Bothy, Deershot Lodge: Zero Books, 2009. Print.

[2] Jameson, Fredric. Valences of the Dialectic. London; Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2009. Print.

[3] Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. New York: Hill and Wang, 2012. Print.

[4] Sontag, Susan. “Notes on Camp” Against Interpretation: and Other Essays. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1986. Print.

[5] Chen, Chris. “The Limit Point of Capitalist Equality.” Endnotes. 2, 2014. Print.

One thought on “‘Comediennes’ (II): “You Might Like Comedies with a Strong Female Lead…””