By Payton McCarty-Simas

While Oedipus Rex is the most obvious reference point for Toshio Matsumoto’s 1969 film Funeral Parade of Roses, upon closer investigation, overt references to Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) also pervade the film. From its opening sequence, which includes a brief recreation of Marion Crane’s final shower before her murder, to a series of direct references to the murder scene itself in the film’s climax, Funeral Parade’s referencing of Psycho is deliberate and pointed. Particularly in its final sequence, Funeral Parade uses this particular intertext (in addition to pointed ruptures in diegesis) to blur the lines between victim and monster as a means of abstracting and disavowing the pathologized figure of the queer Monstrous Other quintessentially represented by Norman Bates.

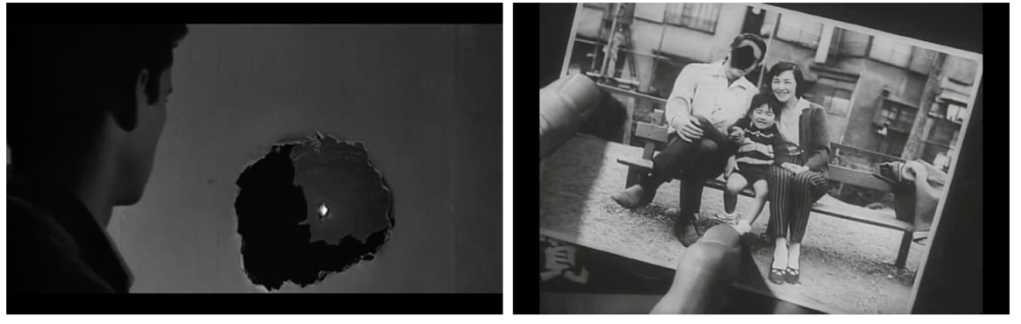

Funeral Parade‘s early reference to the Psycho shower scene is integral to the film’s construction of gender as performative and based in artifice. Prior to this point (approximately ten minutes into the film), the biological sex of Eddie (Peter), the film’s protagonist, has remained ambiguous. Eddie (who will be referred to throughout this essay with they/them pronouns) is introduced abstractly through fragmented close-ups in the hotel love scene which begins the film, then later wearing elaborate feminine attire. This shower scene (which is linked associatively to the film’s final, climactic sequence, though the chronology of events is left ambiguous) destroys any binary assumptions of gender the viewer may have held up to this point in a clear and playful manner while simultaneously setting the stage for the climax.

It begins abruptly, with a shot of a running shower head jutting into frame. Next, Eddie is shown enjoying the hot water, smiling and letting it run over their face in close up. Both shots are almost identical in composition to those which begin Psycho‘s shower sequence–– though the latter notably occurs in slow motion. This shot of Eddie lingers on their face for several moments before tilting down their body, recontextualizing the opening love sequence’s fragmented view for a more cohesive one–– only to be interrupted by a jarring freeze frame of Eddie’s flat, male chest. The sound cuts out and the camera holds on this indicator of biological maleness which, from a heteronormative perspective, runs counter to Eddie’s gender performance. The use of Psycho as a reference point here helps to establish Eddie’s complex relationship with femininity, which will become progressively more ambivalent in the film’s final sequence. The interposition of the biologically male Eddie for Marion Crane, a classic figure of heterosexual sex appeal, disrupts the heteronormative gender binarism of Psycho and works to undermine the pathology at that story’s heart, namely that non-normative gender performance presupposes a violent temperament. At the same time, as the film progresses to its climax and Eddie’s own violent tendencies become clear, aligning them more with Norman Bates, this reference will take on a still more significance.

It is also notable that immediately following the introduction of Psycho as an intertext, with Eddie taking the role of Marion Crane, documentary elements are then incorporated into the film, deliberately interrupting the film’s diegesis at this critical moment of gender destabilization. This documentary footage, interviews largely conducted with members of the film’s cast and which punctuate the film, work to naturalize queerness and feminine performance for males by emphasizing the cast’s comfort with their sexuality and gender. Inserting the first of these interviews at this moment in the film inevitably works further to disavow the queer-negative Oedipal pathology of Psycho and Norman Bates through contrast. Additionally, the first interview immediately following the revealing freeze frame of Eddie’s bare chest begins with a film slate, further highlighting the artificiality the film’s narrative (Eddie’s story, based on the story of Oedipus Rex and replete with references to Psycho, a classically pathologizing tale of gender non-normativity) by showing images of its creation by real queer people who are comfortable, happy and unashamed of their sexual and gender expression.

The deliberateness with which Matsumoto foregrounds diegetic fragmentation, exploding his narrative’s realism and revealing the artifice at the heart of any fiction film, is in keeping with notions of “queer time” as described by Sarah Dyne in her discussion of The Children’s Hour. In this construction, “points of resistance” to a linear, reproductively inflected heterosexual life trajectory (in cinematic terms represented by traditional story structure and immersive diegesis) “propose other possibilities for living in relation to indeterminately past, present, and future others: that is, of living historically” (Dyne, 7). The interrupted, nonlinear timeline of Funeral Parade speaks to this form of resistance to hegemonic structures of cinematic heteronormativity, as does the use of slow and fast motion and freeze frames throughout the film. For example, the slowing of the shot of Eddie in the shower, even prior to the freeze frame on their chest, further denaturalizes or queers the film’s relationship to Psycho, its referent, by placing it outside of traditional narrative time.

The film’s climax, the restaging of Oedipus’ self-mutilation and Jocasta’s suicide, references Psycho in a more fragmented fashion, aligning Eddie and their father, Gonda (Yoshio Tsuchiya), in turns with both Marion and Norman, Psycho‘s binary hero and villain, as a means of complicating the film’s relationship with queer-coded monstrosity. Beginning seemingly where the shower scene left off, the climax begins as Gonda enjoys a (post-coital) drink and smoke in Eddie’s apartment while Eddie is in the bathroom. Looking for a record to play, he inadvertently stumbles onto a book entitled “Father Returns,” which he opens to find a childhood photo of Eddie with their parents–– Gonda and his wife–– ultimately revealing that Gonda’s relationship with Eddie had been inadvertently incestuous. Interestingly, the father’s face has been burned out of the photo with a cigarette, forming a hole through which he must infer his own presence. Much as Norman Bates spies on Marion as she undresses using a peephole hidden behind a painting, this act of voyeurism into Eddie’s private life on the father’s part precipitates the sexual shame and guilt which spurs him to violence. Eddie then emerges from the bathroom in a towel, inviting Gonda to bathe himself as they get dressed. The camera then tracks Gonda as he enters the bathroom, finally settling on Eddie at their vanity as a means of visually connecting the two for the dramatic moment that follows.

Gonda’s final decision to kill himself, in keeping with notions of “queer time,” is represented almost abstractly. In the bathroom, a close tracking shot of each person’s face (or, in Gonda’s case, the absence of his face) in the photo reaffirms Gonda’s certainty of his incestuous transgression. An expressionistic shot of Gonda in medium close up against a black background entirely dissociated from his actual location follows, and is then matched by a still image of Eddie from an earlier scene (in a hyper-stylized Greek dress reminiscent of a classical Muse that both renders the Oedipal connection more explicit and links it to Eddie’s elaborate feminine gender performance: up to this point in the scene, the photo of young Eddie hasn’t been visually linked to their adult self). [1} Gonda finally opens a mirrored cabinet to reveal a long knife (reminiscent of Psycho), which he then unsheaths in a dramatic close up reflected in the mirror. Rather than allowing the viewer to witness Gonda’s suicide, the next shot is a match cut to Eddie, who is shown reflected in another mirror, brushing their hair. Mirrors and associative editing in this moment underscore the layers of dissonance and misrecognition at play–– the confusion between the role of lover and parent between the two characters, neither of whom are innocent of sexual transgression.

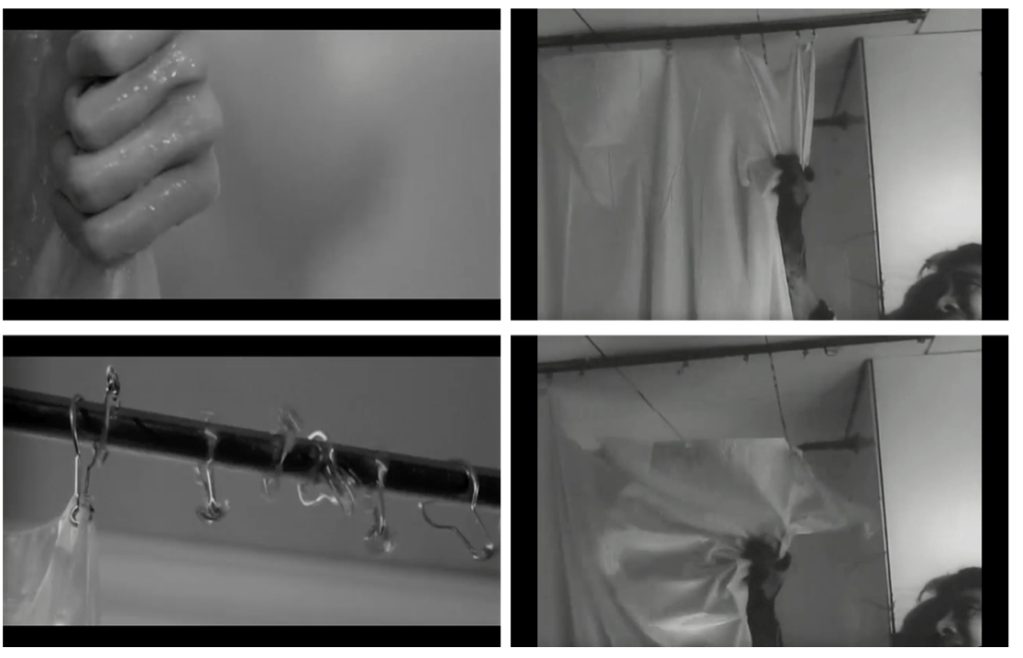

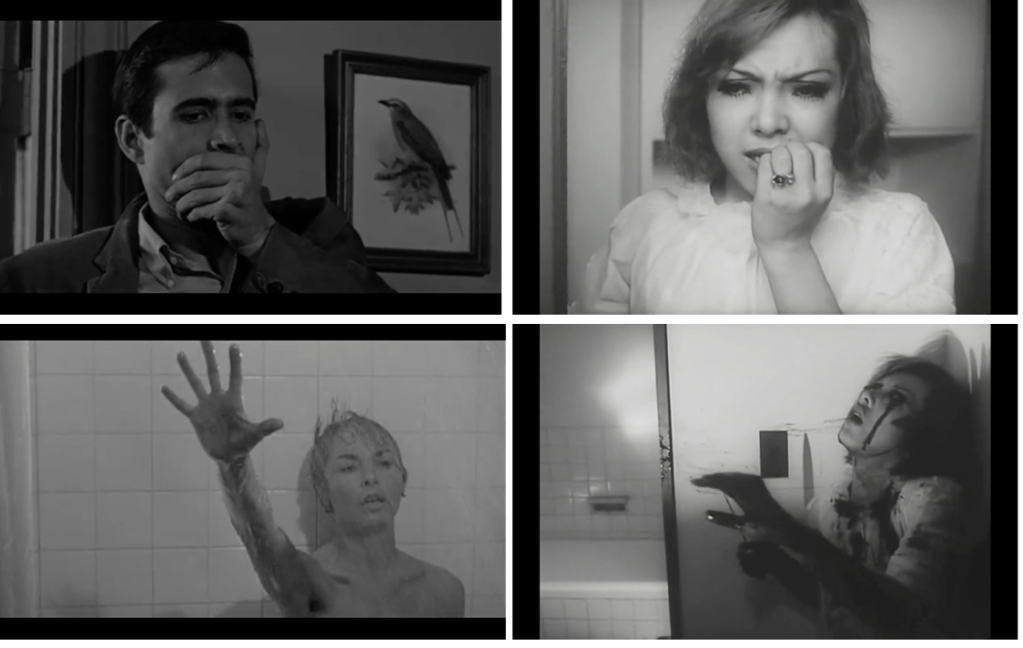

Eddie’s discovery of their father in the bathroom begins what can be in part viewed as a complex recreation of the shower scene in Psycho, with both characters taking the role of Marion and Norman in turns. Eddie enters the bathroom and gasps in shock, putting their hand to their mouth. Gonda is then revealed covered in blood, having slashed his own throat. Blood covers his hands and the walls behind him as he stumbles weakly towards the door, using one bloody hand to steady himself against the wall. The camera follows his hand as he reaches for the shower curtain to hold himself up, but his weight pulls it from its hooks and he falls to the floor, dead. This slow stumbling attempt to maintain balance against the wall is highly reminiscent of Marion Crane’s attempt to keep upright just after she is stabbed. This connection is solidified when Gonda pulls down the shower curtain and falls to the floor, a distinct action taken from the same scene in Psycho. Where Gonda’s discovery of the photograph placed him in the role of Norman, the fraught voyeur and sexual transgressor, here he becomes Marion, the victim of a sexually tinged murder on the part of a “perverse” queer character. Gonda’s suicide, then, through this blending of subject positions, serves as a postmodern reflection of the ambiguous relationship of not just Jocasta to Oedipus, but Marion to Norman, and Norman to himself: unknowing accomplices to an inadvertent act of sexual transgression–– notably, incest and not queer sex–– who are both active in their desire and passive in their ability to change their fates. As prefaced in the Baudelaire quote which opens the film, Gonda in this moment is both literally and figuratively “a wound and a blade, a victim and an executioner.”

In Funeral Parade‘s final minutes, the rapid oscillation of Eddie’s subject position from victim to monster and back again, ultimately serves to disavow the monstrous pathology assigned to their character and reveal the constructed nature of the film’s narrative. Upon discovering Gonda’s body in the bathroom, Eddie, haunted by a shot of their mother laughing at them (previously shown in relation to their recollection/fantasy of murdering her) takes the same knife from where their father has left it in the sink and proceeds to stab their own eyes out. Their reaction to discovering the body (a gasp and a hand brought up to their mouth in the bathroom doorway) is visually similar to Norman “finding” Marion’s body after her death. Once they have blinded themself, they stumble out of the bathroom and reach one hand out in front of them, still clutching the knife, seemingly looking for balance. Just before her death, Marion Crane performs the same deliberate gesture, outstretching her hand as if for assistance. Thus, seeing Eddie replicate this action while still holding a bloody butcher knife in their hand, puts them in a highly liminal position relative to gendered expectations of victimization. Eddie, like Gonda, has become their own victim.

Eddie’s particularly ambivalent relationship to femininity and violence must be read within a larger context of queer pathologization which construes the non-cisgender body as threatening. As Harry Benshoff concisely describes, in traditional Hollywood cinema, “monster is to ‘normality’ as homosexual is to heterosexual” (Benshoff, 2). Norman Bates, the tragic villain of Hitchock’s Psycho,who murders his overbearing mother and her lover, then “pathologically” assumes her identity–– and her clothing–– to kill women he finds sexually appealing, is a quintessential example of this construal of gender non-normativity with pathology.

Conversely, Felicity Gee places Eddie in a different cinematic tradition, that of the tragic film diva, asserting that they represent “the crisis and ambiguity at the heart of a global and social modernization” through an “uncanny” binarism, or “an arbitrary persona of two halves… both… subject of a wider social voyeurism and curiosity, and… someone in control of their sexuality, adopting the female masquerade of femininity in excess.” (Gee, 60, emphasis added). While this is not wrong, inherent in that binarism (and the negative language Gee uses to describe it) is a cinematic legacy of gendered pathologization which the film is clearly referencing. Making another connection to Norman Bates, Funeral Parade, in what is either a flashback or a fantasy, depicts Eddie killing their mother and her lover as a child when their mother mocks them for putting on her makeup, a backstory which hews closely to Bates’ own and which pathologizes Eddie, specifically linking their gender expression to this budding violence.

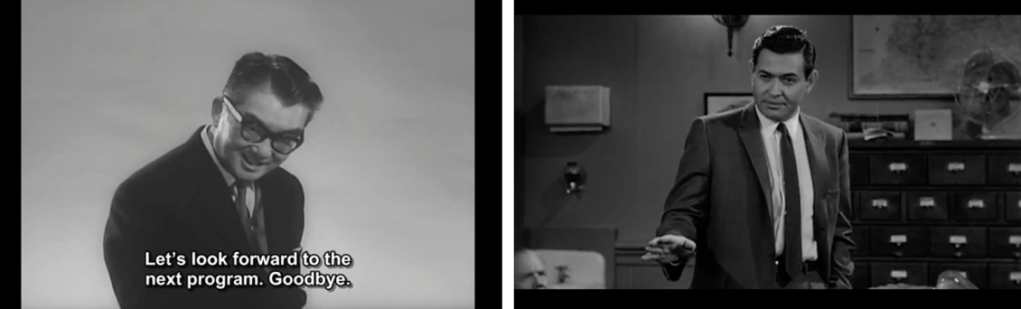

Unlike Bates, however, in the film’s climax, Eddie’s violence is ultimately turned inward, onto themself. Also unlike the opaque murder scene of Psycho, Eddie’s act of self-mutilation is shown in vivid and unexpected detail. Perhaps in part due to the overt references to Hitchcock’s famously non-explicit film and because Gonda’s suicide occurs off screen, Eddie plunging a knife into their eye on screen comes as an abrupt shock of visceral violence. In another unexpected moment of diegetic rupture Eddie’s act of self-annihilation is bookended first by the image of a film strip containing different frames of the same scene, beginning with the shot of Gonda’s body and ending with a shot of the apartment door as Eddie goes outside, an event which will not occur for another few minutes of screentime. This choice to interrupt the narrative at its dramatic peak and highlight its artificiality serves to denaturalize the dramatic and monstrous events taking place on screen. Taking this intervention into the narrative further, as Eddie leaves the bathroom, Matsumoto cuts to a man in a suit sitting behind a desk who comments on the film as a whole, exclaiming, “It was tragic wasn’t it? What a frightening thing!” before encouraging viewers to “look forward to the next film” and bidding them goodbye three times. This conspicuous interruption, which takes place four minutes before the actual end of the film, seems to be an overt and cheeky reference to the “square-up,” or the convention in exploitation films of having a character (or an extra-diegetic announcer) explain the moral of a film at its conclusion–– a trope deployed by Psycho in its final sequence wherein a court psychologist psychoanalyzes Norman Bates.

In this case however, the film doesn’t end with this announcer. Instead, Eddie leaves their apartment and finds their way outside into bright daylight where they are greeted by a stunned crowd of voyeurs on the sidewalk. This final coda is also notably shown from Eddie’s perspective, irrespective of the fact that they are blind, implying a queer gaze which exists outside the diegesis of the film and is critical of the voyeurism of an audience who relishes its ability to consume the image of Eddie as monstrous other. Taken together, these final moments suggest that no easy moral conclusion can be drawn from Eddie’s tragic story, seeming to force the viewer to look beyond the good and evil framework of heteronormative cinema–– a fact already established through the use of extra-diegetic interviews with the out queer cast of the film–– and exist in “queer time,” accepting the multiplicity of queer experience beyond the pathologizing influence of heteropatriarchal filmmaking.

[1} Eddie’s hair, makeup and clothing in this image and the prior scene in which it first appears are reminiscent both of Ancient Greek statuary and of Jocasta in Pasolini’s 1967 Oedipus adaptation, Edipo Re, which is referenced overtly through the prominent, repeated use of its poster as a backdrop for an earlier scene in an alleyway.

Works Cited

-BENSHOFF, Harry M. Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film. Manchester Univ. Press, 1998.

-DYNE, Sarah A. “‘It’s so Queer—in the next Room’: Docile/ Deviant Bodies and Spatiality in Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour.” Miranda, no. 15, 2017, doi:10.4000/miranda.10519.

-GEE, Felicity. “The Angura Diva: Toshio Matsumoto’s Dialectics of Perception. Photodynamism and Affect in Funeral Parade of Roses.” Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema, vol. 6, no. 1, 2014, pp. 55–73., doi:10.1080/17564905.2014.929409.

-HITCHCOCK, Alfred, director. Psycho. Paramount Pictures, 1960.

-MATSUMOTO, Toshio, et al. Funeral Parade of Roses. Matsumoto Productions and Nihon Art Theatre Guild, 1969.

Payton McCarty-Simas is a freelance writer and MA student at Columbia University studying film. Their writing focuses primarily on horror film, sexuality, psychedelia, folk horror, and the occult. Their most recent work has been featured in Film Daze, The Brooklyn Rail, and Film Inquiry.