By Flora Arnold

At its 50th anniversary, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre remains more than ever a perfectly pessimistic parable for America, the land of pure hostility, home of the deranged. The chainsaw itself stands apart, unique in its grisly mystery as a symbol in defiance of signification. As a cornerstone of the slasher genre, director Tobe Hooper’s masterpiece laughed maniacally in the face of the 1970s paranoid obsession with conspiracy, proposing a new answer to the question raised by the horror story of America: no reason.

There have been many critical interpretations of the movie over these decades, ranging from straightforward vegetarian propaganda, commentary on (de)industrialization, capitalism as cannibalism, to a parody of the bourgeois family. For me, TCM is all of these things, and none of them, because, first and foremost, the movie is about white supremacy. The massacre does not pose a question of logic or even desire, but rather a reflection of what Frank Wilderson calls “America’s structuring irrationality: the libidinal economy of white supremacy.”

This is true insofar as the movie is about America—there are obvious American features, like a spring break road trip in a Ford van across a relentlessly sweaty Texas. But each additional element of Wilderson’s conceptualization of white supremacy also simmers beneath the surface. Rural Texas serves as a caricaturish synecdoche for a society structured and restructured both economically and morally by industrial violence; the collision of two culturally disparate families with complex and mystified impulses; and a hippie culture that is at once both ignorantly hedonistic and desperate for meaning in a country devoid of reason and morality.

To emphasize the white-supremacy driven irrational logic of the film, Sally Hardesty, a young woman on a road trip through rural Texas with her brother and friends, only becomes the clear protagonist by subtraction, as her (chosen and kindred) family is murdered one by one. Her astrology-obsessed best friend Pam and Pam’s assiduously average boyfriend, Kirk, are first to go, followed by Sally’s own confidently skeptical boyfriend Jerry—all slaughtered by the film’s iconic Leatherface in a cattle-like role reversal. Her disabled brother Franklin, consistently ostracized from the group and marked for death, is the last to die. The Slaughter family tree is elaborated in reverse, as we meet each member, mysteriously, one by one and we only see the family portrait in full at the finale. We first meet the Hitchhiker by the side of the road, only to later learn he is responsible for the plot-instigating grave-robbing. Then the Cook (also referred to as Old Man) appears as a friendly-enough gas station attendant, and finally Leatherface himself appears all at once, violence and all. Each member of the Slaughter family is re-introduced at the end alongside exposition of the family legacy as industrial slaughterers. Industry seems to tie the circle of family in a knot: we learn obliquely, early on, that the Hardesty family owns that slaughterhouse.

TCM attends to the problem of sense-making immediately. As the grisly first images of the film are incomprehensibly illuminated on screen by a journalistic flashbulb, a radio news broadcast narrates what we are viewing: exhumed corpses, defiled and reconfigured into some kind of statue. This scene transitions to introduce our road-tripping hippies and the broadcast becomes diegetic, as highly ignorable background noise on the dashboard radio of the van. Rather than being shut off or ended, the headlines continue, giving us a snapshot of the political landscape in which we find our characters: the inexplicable collapse of a mental hospital, regional war in South America, mutilations, child abuse. Yet like the brief illuminations of the flashbulb, the fragmented form of the bulletin is legible only to the audience with the full context of the grave desecration. The transition of the broadcast from narration to diegesis not only ominously foreshadows the film’s libidinal violence beyond a coherent politics, it also underlines the ignorance of the main characters.

Hooper’s cold and detached framing of these squabbling college kids is less than sympathetic. They are complicit with the white-supremacist logic of the film and their concerns are dwarfed by the withering Texas sun. Pam tries in vain to explain to her friends the astrological concept of retrogradation and that “Saturn is malefic”—the combination of which spells out a bad influence on the world. The stench of the passing slaughterhouse interrupts both the astrology lesson and news bulletin, and Franklin is compelled to explain the family business of animal slaughter: “They’d bash ‘em in the head with a big sledgehammer. It usually wouldn’t kill them on the first lick. I mean, they’d start squealing and freaking out and everything, and they’d have to come up and bash ‘em two or three times.” Everyone else’s revulsion does little to dissuade his fascination with the process of killing. By the time they arrive at a dilapidated house owned by their family the group appears to us as arrogant and entitled, searching for the help they are self-assured is theirs to receive. These opening moments are key to a close reading of the film. They give us clues to follow as our minds are quickly emptied by brutality. When the chainsaw starts, there is no looking back.

Sally’s survival seems at first to be the least likely event of the story, hammered home by the manic tone of the final shot—but if we take somewhat literally Wilderson’s definition of white supremacy as a libidinal economy, then her survival is a hard-earned transaction on some kind of perverse market. In liberal society, the currency exchanged on this market is now symbolic: expressions of Whiteness are exchanged for inclusion, expressions of Blackness are exchanged for exclusion. But that money is no good in the backwoods of Texas. The Slaughter family have reasserted the primacy of punishment and death in this economy. This process stands in the face of an expectation of conspiracy, what Fredric Jameson famously described as “a degraded figure of the total logic of late capital,” a representational failure “marked by its slippage into sheer theme and content.” TCM offers no such slippage, but a negation thereof. The inability to comprehend and represent the massacre under the logic of capital is symptomatic of white supremacy’s structural irrationality.

No explanation is available for the hippies’ misery. Franklin remains befuddled by the economics of the situation until the very moment when he is slaughtered. Pam is overly comforted by the simultaneous explanation and displacement of meaning by Saturn in retrograde—as she is hung on the meathook and made to witness the inconceivable we cut not to Saturn but the merciless Texas sun. Kirk and Jerry march with red-blooded confidence straight up the ramp to the killing floor. And finally as Sally begs for mercy at the slaughter family’s dinner table she repeats “please” over and over, at once pleading for mercy and reason. Neither can be found.

One expects to find a sort of rationality within the network of connections between the Hardesty and the Slaughter families. Sally and Franklin’s grandfather owned, operated, and modernized the local slaughterhouse that previously employed the Slaughters. Could the Slaughter family be out to get even? There is an implicit tension set up between the unemployment of the Slaughter family and the Hardesty family business by the ramblings of the Hitchhiker and ominous warnings of the gas station attendant that is later reintroduced as the Cook. The hippies only stumble across the Slaughter house when there is no gas available (is this a lie? was it a trap all along?) and the Cook warns the group to stay put and wait for the gas delivery (this may be genuine, the Cook is later concerned with the Hitchhiker’s carelessness). These clues hinting at a purposeful conspiracy, either of family feuding or simple predatory scheming, fly in the face of the actual characters doing the slaughtering.

The Slaughter family themselves are devoid of reason, eschewing conspiracy. This is the horror of the film. The monstrosity of Leatherface is unthinking, animalistic. The longest scene we see personally focused on him depicts distress, not malevolence—following the invasions of his space he paces fearfully through the house, moaning in confusion. Similarly, the Hitchhiker is impulsive (his invitation of the hippies ‘to dinner’ notwithstanding, but if that’s a trap then it’s a pretty bad one). He seems to be propelled by some unknown magic code or perhaps simply instinct. The lynchpin then to an (ir)rational reading is the Cook, whose calculated malice in tricking and capturing Sally provides the only moment of thinking intentionality. Yet at the dinner table he states the matter clearly: “It’s just something we gotta do.” Thus the family hides no scheme other than hunger and memory. They are propelled forward by the irrational machinations of white supremacy whose libidinal economy continues to circulate even without Blackness to punish and exclude.

The chainsaw itself, like the Slaughter family, is uniquely irrational. It is oddly distinct from the other weapons mentioned or used: the knife, the mallet, and the captive bolt stunner. The Hitchhiker cuts himself and slashes Franklin with Franklin’s own pocket knife. In isolation, that scene has a bizarre mood—like the hippies, we are aghast at a seemingly inexplicable act of violence. But in context, the knife is a logical tool of the Slaughter family business and an obvious point of fixation for the Hitchhiker’s bloodlust. Later, Leatherface kills Kirk with a mallet in exactly the manner of the old slaughterhouse procedure described by Franklin and the Hitchhiker, including a second whack to end Kirk’s convulsions. In fact the sliding metal industrial door at the back of the Slaughter family’s house, and the low ramp leading up to it, evoke the functional architecture of the slaughterhouse.

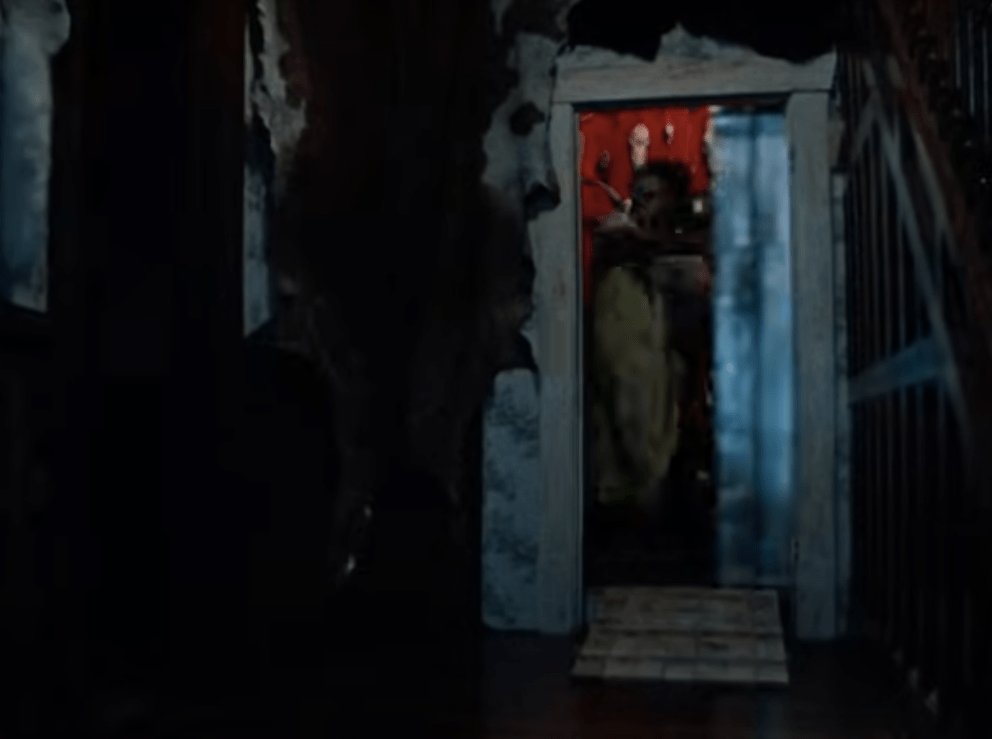

This parallel, between Kirk’s death and industrially systematic cattle slaughter by way of Franklin’s detailed description earlier in the film, is accentuated by the matter of fact tone of the scene. Our first sight of Leatherface is hardly a jump scare, his sudden appearance behind Kirk deflates rather than captures the tension of Kirk’s increasing confusion, and the camera shows little detail. By the time Leatherface yanks the metal door shut in front of our intruding eyes we have barely processed what is happening. This makes Leatherface’s mallet swiftly efficient—even professional. The briefest lingering on Kirk’s convulsing feet before the second whack reminds us that this could have happened even more efficiently. We never see the captive bolt stunner, a pneumatic device that ejects a metal rod at deadly speed described in the van as the technological successor of the mallet. There is a straight line from knife to mallet that is cut off on its way to the bolt stunner, and which does not lead to the chainsaw.

We are first introduced to the chainsaw not as a weapon but as a misplaced industrial tool. Leatherface inexplicably butchers Kirk’s corpse with a chainsaw rather than following the cattle metaphor to its logical conclusion with a meat saw or butcher knife. In a movie celebrated for its realism, the strange choice of the chainsaw stands out. Tobe Hooper has notoriously stated that the idea for the chainsaw came to him as a violent fantasy in a hardware store surrounded by holiday shoppers, while he already had the themes of the story in mind. It was a conveniently meaningless piece of violence.

The chainsaw, in this sense, comes to symbolize this structural irrationality, both as an actual plot device and as a poetics of ambivalent signification. There is no conspiracy, only a reckoning with the totality of American white supremacy: a set of mouthless teeth, artificially motorized and ambiguously animated, ripping flesh.

Author Bio: Flora Arnold is a graduate student in Critical Studies at the Pacific Northwest College of Art. When they aren’t watching movies or pondering the horrors of capitalism, they listen to metal. Their writing on music has appeared in Treble Zine.

Works Cited

Baumgarten, Marjorie. “Tobe Hooper Remembers ‘The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.’” The Austin Chronicle, Oct. 27, 2000. https://www.austinchronicle.com/screens/2000-10-27/79177/

Hooper, Tobe, director. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. 1974.

Jameson, Fredric. “Cognitive Mapping,” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Wilderson III, Frank. “Gramsci’s Black Marx: Whither the Slave in CIvil Society?” Social Identities 9, no.2, 2003.

Wood, Robin, ed. Barry Keith Grant. Robin Wood on the Horror Film: Collected Essays and Reviews. Chicago: Wayne State University Press, 2018.

go off!!

LikeLike