By Sylvia Faichney |

There are few practices that display the visual shift from modernism to postmodernism as succinctly as design does, especially in its interior domestic architecture. Through the generous application of textiles and the structural renovation of interior architecture, the domicile transformed into a robust space, offering design as a critical tool to unpack social and political form. This dramatic historical transition is captured, dramatized even, within the mediated and duplistic documentation of advertising. Looking at an advertised interior is looking at a characterisation of domesticity, typically displaying idealistic personalities, exploring nuances of gender and class relationships. Thus, these advertised dreamscapes can be seen as sites of struggle. The 1970s is a particularly fruitful era for design that illustrates these visual, social and technological developments. The interiors rendered in this period capture the politics of labor and gender as they parallel the structural and technological revision of the home. [1] While in political social movements, women rioted to direct attention to repressed reproductive labor issues, at home the labor was ‘liberated’ through the open floor plan.

Historically, the kitchen is necessarily “deeply social and political,” acting as the ambassador of emerging technologies, social sciences, and political propaganda as well as registering the technological shift from modernism to postmodernism. The modernist kitchen foregrounded an efficient ethos “function before form” [2] as embodied in Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s design of the Frankfurt Kitchen. Later, Postmodern design would invert this functionality in favor of communicating pluralism, comfort and personality.

In 1959, the postmodern kitchen became a national symbol at the National American Exhibition in Moscow, where a lemon-yellow kitchen, located in a full-scale ranch style American house became center stage and where ‘technology was to be measured in terms of consumer goods rather than space and nuclear technology.’ [3] The General Electrics kitchen sparked the unprecedented ‘Kitchen Debate’ which has cemented the kitchen as a symbolic site of social, technological and political cathexis. The debate used the kitchen as a means to stress the strengths of each country with the U.S. model illustrating democratic individualism and the Soviet Union modeling socialistic austerity. The American individualistic vision took the form of “pluralism:” hedonistic consumption and domestic modernity became an international symbol. President Nixon promoted the General Electric kitchen at the exhibition as a ‘typical’ American kitchen of that time, accessible to all US families. This fantasy became more elaborate with the Frankfurt kitchen, representing an imagination of pluralism and individualistic decor.

As the seventies wore on, the introduction of a global market was seen in the kitchen through the proliferation and accessibility of international textiles. The promotion of a king sized bed insinuated the sexual revolution, and the broken barriers from kitchen to living room symbolized the supposed liberation of isolated domestic labor. However, the forms of “pleasure” promoted through advertising representation do not solve problems of race and gender, but rather obscure them. As the advertisements demonstrate, homes are filled with white bodies smiling, producing images of beautiful typically white women in clean and inviting spaces.

Rendered within these curated spaces is a masked duplicity of the postmodern domestic interior. Who benefits from the transformation and purchase of ‘labor saving’ goods? Who gets to ‘enjoy’ wielding them? Undoubtedly, the expanded space and new appliances are promoted as if they were made to benefit the white female consumer. What is not underscored is that underlying the success of these spaces and objects is the notion that housework equates to pleasure. These print advertisements reinforce patriarchal ideologies of domestic life that promote performative gender and work relations. This curated advertised dreamscape must be deconstructed in order to uncover its ideological premises. Following the methodologies of sociologist Ann Oakley, as well as the discourse of representation presented by Stuart Hall, I will examine an Eastham E-line advertisement. This will reveal a signification system that works at transcoding domestic labor into female pleasure, rendering domestic labor invisible. [4]

Representation and Housework

“Your kitchen should be more than somewhere you do cooking” is the heading of The Cushionflor Kitchen Collection advertisement shown above. Published in Good Housekeeping‘s June 1971 issue, the advert juxtaposes two images that showcase the “cushion collection” which is “easy to clean” and durable floor coverings, printed by the latest technology. [5] It goes on to proclaim that the kitchen needs an update: a necessary renovation that would enhance ‘your’ experience hosting, the vibrancy of everyday life and drudgeries of housework. Quixotic scenes such as those pictured in the ad above, are enabled by and facilitators of ideologies that permeate the domestic sphere. The social and textual environments reproduced in these spaces are conductors of enjoyment. In these depictions, the signifiers of labor are minimized, thereby simulating expected and accepted gestures that are meant to resound within the interiors. These renderings are political, the presence of only white, thin, clean models in the spaces offered to us by the ad above is evidence of norms that were circulated and accepted within the social.

The social system of signification is categorized by Stuart Hall as ‘the politics of the image’. Hall describes ideology as “mental frameworks [that are used to] figure out and render intelligible the way society works.” [6] By acknowledging the ideology of the image as a circulated system of communication whose function is to enforce the accepted “way society works,” we can begin to interrogate representations of the home and labor. In this framework, women become naturalized signs for the commodification of labor and desire. Their placement and role within the domestic is a matter of common sense, erasing the notion of housework as labor and painting it as pure pleasure.

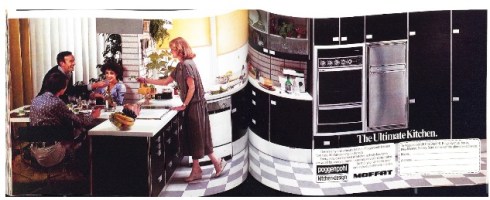

Within these advertised spaces, the signifiers of domestic labor are dissolved along with any hope of female autonomy from the domestic space. The represented interior, such as The Ultimate Kitchen, showcases this relationship through stylistic coordination of the female and the kitchen. Her uniform matches the kitchen decor, as her dress parallels the stainless steel appliances, and her hair is complimented by the soft yellow shades. This naturalization is further justified through the linking of consumption with pleasure. [7]

In opposition to such modes of signification, second wave feminism aspired to reveal images of domestic bliss as propaganda for domestic inequality. [8] Oakley illuminated this dissonance between representations of harmony and the reality of inequality in a series of interviews conducted with women working as housewives in the 1970s. For example, when discussing the monotony of housework, which contributes to its image of being an ‘easy’ or ‘enjoyable’ occupation, Lorry, a driver’s wife, stated that: “[washing up/housework] is never ending. You’ve no sooner done one lot of washing up then you’ve got another lot, and that’s how it goes on all day.” [9] Furthermore, when discussing the difficulty of a housewife’s job in contrast to their husband’s, a “Plaster’s wife” posited that:

Housewives work harder. My husband’s always coming home and saying ‘Oh I sat down and talking to so-and so today or ‘we had a laugh today with so-and-so … I don’t do that, I never sit down.

Oakley claims that revealing the invisible could be a “major tool of feminist revolt” in that it builds a comprehensive understanding of the way in which women “internalize their oppression.” [10] In these interviews, Oakley, not unlike autonomous feminists, challenged the assumption that women were “naturally good at” doing housework, or that they naturally enjoyed this activity. This is underscored in a response from a “Supermarket manager’s wife” who, when asked about her relationship to her role as a housewife, proclaimed:

I like housework. I’m quite domesticated really. I’ve always been brought up to be domesticated – to do the housework and dust and wash up and cook – so it’s a natural instinct really. [11]

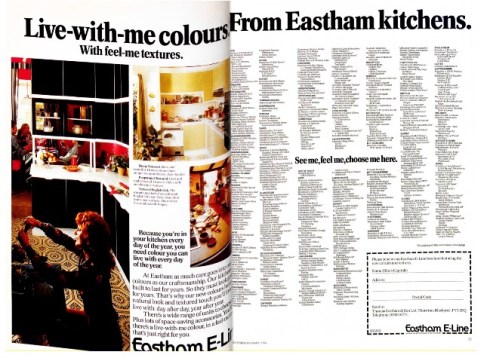

Introducing us to the ‘70s kitchen, Eastham E-like fitted kitchens reveal the past, present, and future naturalization of women within the domestic kitchen.

The advertisement for Eastham E-Line Kitchens was published in the December 1975 issue of House and Garden. The lifestyle represented within the domestic interiors presented in these advertisement foreground signs of joy and pleasure, equating labor with entertaining and entertainment. This promotes gender inequality within the domestic sphere, by diminishing signifiers of labor being labor and further endorsing the characterisation of domestic work as women’s work.

Although a product of the modernist Frankfurt School, an institution which touted social reform through structural efficiency, the fitted kitchen continued to be a staple in developing technologies regarding the kitchen, most likely due to its perceived flexibility, affordability, functionality and attractiveness. [12] Eastham E-Line was under the company of Thomas Eastham & Son Ltd, applying the blueprints of fitted kitchens, while adding new technologies and style. In the 1970s, they began implementing new material, subsequently producing more affordable and diverse options, while incorporating technologies within the space by using polystyrene linings to metal kitchen cabinets. [13] Eastham’s fitted kitchen were typically made out of formica, rather than traditional materials such as steel or wood. Formica is laminated plastic, intended for “easy cleaning” invented in the 1930s. This “easy to wipe” material was promoted as a labor saving object. [14] This infers that one of the housewife’s duties is “labor saving.”

‘Sleek and Beautiful’: The ebony textured kitchen from Eastham

Cast with ebony cabinets and ivory countertops, the “ebony textured” kitchen flows out into the dining room, where a white woman is seated facing the kitchen, engaged in conversation with two white men, their backs turned to the kitchen, one of whom is lifting a glass of wine. Working in the kitchen is another white woman, smiling while kneeling down to season a meal in the oven. The lifestyle provided through the ownership of Eastham’s kitchens is meant “to be seen and felt” as sociable, warm “sleek and beautiful.” Interpreting the connotative signs, the open floor plan invites sociability, as the women preparing the food are able to hear and be seen by their guests. This pleasurable way of life is signified through the guests in the background smiling, and validated through the depiction of a gentleman holding a glass of wine, leaning back relaxing.

The advertisement’s construction of a “lifestyle” naturalizes female performed domestic labor as enjoyable and unalterable. Eastham offers a slice of ideology endorsing the patriarchal vision of how domestic labor is divided within the home. It is presumed that an Eastham kitchen would not only help the heteronormative couple’s lifestyle, but imagines an efficient, “labor reducing,” “easy to clean” space, at the price of erasing domestic labor. What is visible is a female kneeling down, smiling, bending over a hot stove while still remaining a vision of beauty with barely a hair out of place. She, like the kitchen, is sleek and beautiful, while being a conductor of labor. The connotations of the women’s low, bending pose is described by Erving Goffman in his text Gendered Advertisements as representing childish behavior. As he puts it, “the ritualization of subordination” is achieved by manipulating and framing social connotations that are associated with body posture, location, positioning, and elevation between males and females in an image. [15] In the Eastman ads this is done by placing the the women working in the kitchen in the foreground, below her guests. She smiles despite her visual and spatial isolation from leisure and sociality.

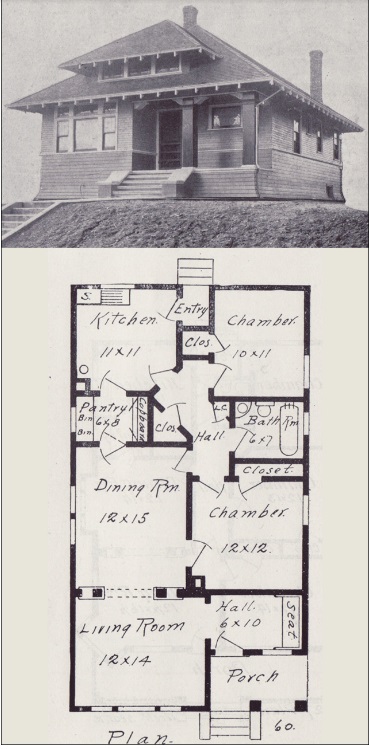

Up until roughly the 1940s, the kitchen was physically isolated from other parts of the home, as the floor plan of the Bungalow illustrates. Prior to the advent of bourgeois middle-class domesticity, bundled up in a nice package classified as the nuclear family, the upper-middle class kitchen was occupied by servants. The planning strategy was executed with the intention that each room would have a distinct function, in line with the class-divided occupants of the house. Increasingly, in the middle of the century, more typically white homeowners would become middle-class and were able to afford homes. This transformation extended the purpose of each room, given that middle class people generally couldn’t afford servants, and thus had to expand their own functions. The open-floor plan would presumably transform the kitchen into a space of sociability in line with these historical transformations. However, this spatial shift did not alleviate the plight of the worker, now embodied in the housewife. Although the wall dividing the kitchen from the dining room, labor from leisure, had dissolved the isolation remained.

The kitchen as dreamscape, a space that purports domestic bliss, is the women’s stage. Throughout the industrial age, as floor plans developed so did the technology and the shape of the kitchen. As the space adopted a new science, influenced by the emphasis of productivity, electricity, and affordable materials, an isolated kitchen became obsolete, as did the necessity of multiple servants. [16] Consequently, the kitchen evolved as a ‘women’s space.’ Considering that it is the site which produces nourishment for the family, and in this context affective labor, it is a space culturally designated to the wife and mother. Thus, others do not feel obligated to contribute to its process of production. [17] Here, visibility does not equate to women’s sociability or ‘liberation.’ Rather, her role as a housewife increases to encompass entertainment and spectacle, akin to the advent of the cooking show. This gendered performance is glossed over and naturalized: “because you’re in your kitchen every day of the year….”

The “you” that is referenced extensively here refers to any and every reader of the December issue of House and Garden, the majority of whom are women. [18] The advert interpellates the woman reader as someone who seamlessly identifies with and anticipates happiness within the kitchen interior and thus with the product – indeed, “living with it!” The pleasure of submissiveness is an essential ingredient here. Domestic masochism is part and parcel of the internalization of patriarchal standards of labor and gender roles within the home.

The Eastham dreamscapes imply class mobility linked to spacious and opulent interiors. The structural transformation of these interiors communicate a cultural capital associated with the upper class in Britain during the 1970s, emphasising Robert Venture’s doctrine “more is more.” However, the question remains, whose mobility? The woman cooking the meal in the kitchen is not released from her work through the ownership of these interior spaces. She is bound by them. In this context, the notion of a transformed lifestyle through the increased visibility of the Eastman kitchen appears as a myth. Despite connotations of warmth and pleasure in these transformed kitchens, women’s work did not fundamentally change nor did access to sociability.

The lifestyles that appear within these dreamscapes were once deconstructed through the feminist activism surrounding housework and the unequal division of labor. Easthams’ advertised kitchen glosses over these structural inequalities and forms of discrimination by presenting social scenarios that promote the sign of women as commodity, a conductor of production within the home. The language used promotes their products as beneficial to the overall feeling of being in a space. They proclaim “Look. Touch. Feel.” They are an injunction to enjoy. The enjoyment is gratification she may receive from her placement as a worker in the kitchen everyday. Consequently, the fantasy of the kitchen as a liberated site through visibility has fully evaporated.

This rhetoric assumes that consumers will engage in a form of authority and autonomy when choosing their products. The statement, “it’s your space” implies that liberation can be defined by the ability to decorate one’s space with durable, enjoyable, products. [19] Oakley posits that the ability to “be your own boss” was perceived as one of the “best things” about being a housewife. With this comes the fantasy of controlling work, time, and space. [20] Oakley concludes that ultimately this autonomy and authority over the self was an illusion of control, given that these privileges were limited to decorative ambitions, which must be contained within the boundaries of what was provided and expected by the husband. [21] As Silvia Federici and Nicole Cox posit in “Counter-planning in the Kitchen,” “the male wage is crucial for the survival of the family even when the wife brings in a second wage.” On the other hand, the emotional labor provided by the mother and wife is an”‘act of love” therefore justifying the absence of a wage, subsequently dissolving the ultimate sign of labor as it is measured in capitalistic terms. [22] Oakley, Federici and Cox insinuate that the domain of the house is tethered to a social hierarchy of the family and capital, where unwaged domestic labor and subservience are exchanged for the male wage.

Eastham promotes their kitchens as a means to enhance the female’s ability to perform labor, given that in return she will feel, i.e. enjoy her labor. The absence of the men’s attention, contribution and interest in preparing meals confirms that the kitchen anticipates her labor, not his, cementing the social norms of structural inequality. The men in the advertised interiors are literally and symbolically dislocated from the site of labor and left echoing in the background as passive audiences, providers, and consumers. [23] Stuart Hall notes that communication is always already linked to power. [24] In the Eastham ads, power is made evident through the physical absence or absence of working males. Thus, in this case dominance is is asserted by the physical recession of those in power. [25]

The Eastham advert both endorses and enforces the social image of women being (working, performing, entertaining, caring) in the kitchen everyday. The advertised interior embodies pleasure as a byproduct of labor. The politics of the image displaying labor as enjoyable consequently rules out the kitchen as a site of struggle for gender equality. The housewife, the women in the ad, which is every women in a kitchen, is meant to be happy through the ability to have the kitchen that looks like she wants, a place where she will be able work happily. It is almost as if the kitchen itself will benefit from her labor. It depends on her presence, for it to be touched, felt, used by her for the kitchen to be a worthwhile space.

The lifestyle of harmony presented within the “ebony textured” Eastham interior representation is reliant on the female consumer, the domestic worker, to be complacent in her role as the lone source of unproductive labor. The class mobility offered through the increase of cultural capital is gendered. The leisure embedded within the dreamscape is dependent on the subordination of female participants. Eastham and Cushionflor adverts do not mention or take note of any labor, outside of insisting that they are “easy to clean.” This advertised interior presents a false, merely visual, liberation of women. The nod to equality in this reconception of space should be dismissed as a mere gesture and a commodification of women’s struggle.

Works Cited

[1] In the 1970s, there were several studies regarding the representation of women within advertising. Andren et al. (1978), through an extensive study of ads appearing in 1 1 American magazines in 1973, determined that women are associated with housework 1 1 times more than men and that men are associated with work outside the home three time more often than females. As well as Erving Goffman sociological investigation of the medium, titled Gendered Advertising.

[2] Penny Sparke, The Modern Interior, (London: Reaktion Books, 2008).

[3] Ruth Oldenziel and Karin Zachmann, Cold War Kitchen: Americanization, Technology and European Uses. (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2009): 6.

[4] Ellen Malos, The politics of housework (London: Allison and Busby, 1980.): 7-42.

[5] Why Choose Vinyl” Consumer Products by Forbo, Forbo Flooring Services, [n.d].

[6] Stuart Hall, “The Problem of Ideology-Marxism without Guarantees” Journal of Communication Inquiry 10.2 (1986): 29-30.

[7] Sherry B. Ortner “Is female to male as nature is to culture?” Woman, culture, and society. Eds. M. Z. Rosaldo and L. Lamphere (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1974): 68-87 describes that distinction. As well as various other texts, such as Kate Millet, Sexual Politics (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1969).

[8] Pat Mainardi, “The Politics of Housework” The Politics of Housework ed Ellen Malos (London: Allison and Busby, 1980): 99-104; Suzanne Gail, The Housewife, The Politics of Housework ed Ellen Malos (London: Allison and Busby, 1980): 105 -112.

[9] Oakley, The sociology of housework, 50. 195 53

[10] Oakley, The sociology of housework, 195.

[11] Oakley, The sociology of housework, 53.

[12] Karen Melching, “Frankfurt Kitchen: patina follows function”, V&A Conservation Journal No.53 (2006): 18-20.

[13] Margaret Duckett, “New furniture: the domestic market” Design Journal 242 (1969): 44 -55.

[14] Johnson and Lloyd, Sentences to Everyday life: Feminism and The Housewife.

[15] Erving Goffman, Gendered Advertisement, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979): 48.

[16] Although the amount paid domestic laborers decreased, they did not disappear. Housekeepers, butlers, nannies, as well as other domestic laborers, were often still employed within these spaces and lack significant representation within the advertising interior of this period. These workers were typically non-white, lower class individuals; therefore the lack of representation is concerning. The invisibility of these individuals is in accordance with the expectations of them. That is, they were to be unseen. The openness of the newly adopted kitchen design renders paid and unpaid domestic laborers as invisible.

[17] Sherry B. Ortner “Is female to male as nature is to culture?” Woman, culture, and society. Eds. M. Z. Rosaldo and L. Lamphere (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1974): 68-87.

[18] Joan Barrell, and Brian Braithwaite. The business of women’s magazines. (London: Kogan Page, 1988).

[19] There have been several texts, I will reference here Sentences to Everyday life: Feminism and The Housewife where decorating the domestic interior is seen as a form of agency, producing a level of stimulus that would give the housewife a form of power. This is not necessarily the case, given that it still continues to delegate decorating as a woman’s role. Perspectives such as this is one that I think should be reconsidered.

[20] Oakley, Ann. The Sociology of Housework. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1985, p. 42.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Silvia Federici and Nicole Cox posit, “Counter-planning in the Kitchen”, Revolution Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland and Brooklyn: PM Press, 2012), p. 35

[23] Ellen Malos, The politics of housework, (London: Allison & Busby, 2008), p. 25.

[24] Stuart Hall, Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices, (London: Sage, 1997).

[25] Ellen McCracken, Decoding Women’s Magazines: From Mademoiselle to Ms. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1992).