By Justin Hogg |

This is part of a Blind Field series on Cover Songs. View the first and second installment.

In Ingeborg Bachmann’s novel Malina (1971), the main character, a woman named Ich, (I) recalls a dream:

I can’t look at my father anymore, I cling to my mother and start to scream, yes,that’s what it was, it was him, it was incest. But then I notice that not only is my mother silent and unmoved, but from the beginning my own voice has been without sound. I’m screaming but no one hears me, there’s nothing to hear, my mouth is only gaping, he’s taken away my voice as well, I can’t pronounce the word I want to scream at him, and I’m going crazy, and in order to stay sane I spit into my father’s face, but there’s no saliva left, hardly a breath from my mouth reaches him. My father is untouchable. He is immovable. To keep the house clean my mother sweeps away the trampled flowers in silence, the little bit of filth [1]

Ich’s father, a central figure throughout the novel, appears in her dreams often, always as a force of violent oppression. In other dreams he is blinding her, trying to take out her tongue so she can’t scream, burning her library, throwing her in a gas chamber. It isn’t difficult to make the connection to fascism, the novel taking place in various parts of Austria with allusions to Nazi Germany and her father’s involvement all over. In the final pages of the chapter, Ich comes to the realization that her father is not really her father, but her murderer in the eternal war of man’s violence towards women. Through the manifestation of the figure of the father, Bachmann tells capital H history (Nazism, fascism) through the personal relationship, the little h history of a father and daughter. Bachmann herself saw fascism as beginning in the relationships between man and woman. She didn’t just see it as those big events which accumulate in a society and lead to the large scale eradication, say of millions of Jews, but also as the slow and daily occurrence of men killing women.

This eternal war and these murders, as in the passage above, are enacted through language. For what is clear not only through Ich’s father appearing mainly in dreams, but also in the insistence on his taking away her ability to speak (though there is no one around to even hear her), is that he comes to stand in for the Symbolic order itself — as Jacques Lacan describes, as that in which speech is constituted. Only through a man, beginning with Ich’s father himself, is Ich able to to be heard and recognized as a subject in this order.

Here, the father is the silencer, as well as the “untouchable,” “immovable” object of the daughter’s desire. This libidinal template helps explain the plight of women in the field of music and sound technology. How can women create sound when faced with an entire order which functions on the basis of their silence? And further, how do they keep attempting to be heard when the sounds they do create are made unintelligible because there is no one listening, or worse yet, the dominant order actively works to distort the sounds women make in order to protect men? Is it enough to simply be heard, or is there a mode beyond recognition that can destabilize the order itself.

1. That’s The Way Boys Are – Y Pants

Y Pants formed in 1979 in the same social and political realities that gave life to the early music of Lizzy Mercier Descloux and other artists in New York City – ‘no wave’, a burst of art against punk, new wave, and the status quo. They were made up of Verge Piersol who played on a Mickey Mouse drum set early on, Gail Vachon beating away on a toy piano and Barbara Ess who worked the thumb drum and sung the lead vocals. Their incorporation of instruments assigned ‘for kids’ demonstrated a fundamental congruence to no wave’s principles: if one were rejecting rock ‘n’ roll and punk rock, then they must reject the instruments used to make that music as well. They only released one full record, the 1982 Beat It Down which came out on NYC noise legend and weirdo Glenn Branca’s Neutral Records, the same label which has in its pedigree such seminal no wave/industrial/noise records as Sonic Youth’s self-titled LP, Confusion is Sex, and Swans’ Filth.

Y Pants were art freaks, unconcerned with producing familiar and acclimatized sounds of the everyday and domestic. Instead, they messed with (or detourned) explicitly avant-garde and radical art traditions with the mission of exploding them. This project was advanced through different media. Barbara Ess took photos with a pinhole camera which created tenebrous and contoured subjects. Gail Vachon was a filmmaker. More impactfully however, this was demonstrated through their musical output. On the same LP, they masterfully detourn Emily Dickinson’s poem “I heard a Fly buzz – when I died,” and re-present it on “The Fly,” transforming the morbid poem into a synth-driven, bedroom dancing banger. Elsewhere they covered the Rolling Stones song “Off The Hook,” turning it into a springy off kilter post-punk force. So when I speak of Y Pants, I’m speaking of cover song experts.

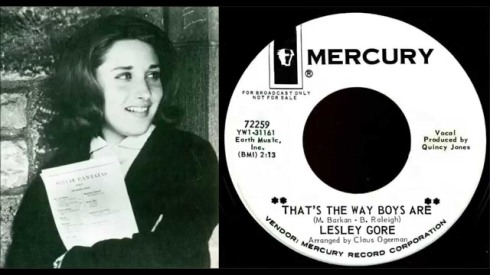

“That’s The Way Boys Are,” was written by two white men, and sung by Leslie Gore in 1964. I call attention to this historical fact because the tone of the song and the actions that occur in it do not fall on the shoulders or within the imaginary of women, but instead arise out of man’s imaginary which attempts to name how women should act and react in their relationships with men. Because of this distinctly male authorship, the song’s lyrics forgo the possibilities of communication in favor of the submission to a naturalized masculinity — at the expense of the song’s presumably female speaker. When this woman sees her partner checking out other women when he is with her, she doesn’t chew him out for his gross behavior, but remains silent as women are supposed to, choosing to avoid gazing at his gaze, and thereby remaining passive: “Not a word do I say/I just look the other way.” Perhaps her attention focuses on street flowers or the swollen clouds in the sky. All of this is preferable to challenging masculinity, to communicating to her partner that his actions “hurt deep inside” and make her want to die. When the speaker of the song relates that her partner is violent to her — “rough,” either physically or verbally, in addition to snubbing her — she again chooses to hold her tongue, submitting to the falsity that he really does love her but is just afraid to show it. It all finds a storybook ending: his return, her forgiveness, kisses and kisses. And as listeners we know that this story will repeat itself, because “that’s the way boys are.” And these are the social relations of men toward women that are supposed to be overlooked and ultimately accepted.

In his book In The Fascist Bathroom, Greil Marcus writes very briefly of the Y Pants cover, noting that their version demonstrates that in rock ‘n’ roll, “Metaphors are turned around” [2], and that they [Y Pants] found, “. . . the abyss in a harmless old pop song.” While I would challenge Marcus’s use of “harmless old pop song” — namely that the kind of cultural norms that the song’s lyrics propagate are still tolerated and lived at the expense of women everyday — I would like to explore this idea of the metaphor here briefly.

Marcus’s conception of rock ‘n’ roll as a metaphorical sphere is in line with Lester Bangs’ assertion that rock ‘n’ roll is an arena in which you reinvent yourself. In Marcus’ view, rock ‘n’ roll is a place for gestures, tropes, and signs, and can therefore not be read through a literal, mundane lens. With this in mind, we can read “That’s The Way Boys Are,” sung by Leslie Gore, as a metaphor for patriarchal values and masculinity. The Y Pants’ cover, however, “turns around” that master trope, disrupting the fantasy of universal masculine authenticity through focused sonic interrogations. It is true that we cannot change the mastered 1964 audio recording of Lesley Gore’s “That’s The Way Boys Are,” and more importantly, the social relations of men towards women in the song. We can however find that change occurs on both fronts through the radical altering of a cover song.

Y Pants turn around the metaphor through a number of disorienting sonic decisions. Firstly, their cover is mostly sung in acapella–singing without instrumentation. This acapella comes as a surprise not solely because it is a departure from the rest of the LP which features the band banging away incessantly on toy instruments and synths, but also because of the way the singing is executed. In the original version, Gore’s speaker inflects her voice at every moment of expected pain, putting her singing in line with the naturalized lyrical content. Unlike “You Don’t Own Me”, which marks a much different approach to the way Gore sings (she keeps her voice medium-low before erupting in her commands to an addressee), here we are confronted with everything that we already expect: her hiccupy doubling of lyrical lines, the matching of melodious vocals with the cheery and uplifting choir of backing singers and piano. When she sings “That’s The Way Boys Are,” “Boys” is sung higher and drawn out in accordance with the strings, suggesting the speaker’s compliance with these unchangeable male subjects. Even at the end of the song, when the speaker has a slight shift in delivery–stating, “Well now/I said/Hear me that’s the way boys are”–this matter of fact deliverance only reinforces the speaker’s own belief in and submission to a set of social relations which undermine and oppress her. One might find the same kind of unflappable affect in The Crystals track “He Hit Me (And It Felt Like a Kiss)” – written by Gerry Goffin, Carole King, and Phil Spector.

In the Y Pants cover, the acapella style works to destroy this complicit affect. The singer’s affect is free from the masculinized discipline of sentimental instrumentation. What we are left with is a stark engagement with the speaker’s voice. The speaker does not make her voice happy or cheerful, which would point to an overt mockery of the patriarchal themes in the song. Instead, she uses just four vocal tones in the first line, tones clearly marked by a difference from one to the next, as stressed here by italics and bold: “When I’m with my guy and he watches all the pretty girls go by.” The majority of the line is sung in one tone, with the last two words, “go by,” indicating the point at which her voice sings two very low notes. Where Gore’s version essentially bounces between very a high and low glissando, Barbara Ess of Y Pants makes the conscious decision to keep the entire vocal line flat, minus three tones. The two low notes lead into the refrain, which sound as though they are sung by the two other members of the band.

As the whole of Y Pants sing it, the line is stressed like so: “That’s the way boys are.” Like the single voice before, the refrain is sung in the same deadpan, unemotional (and here I am marking emotion as that which is inflected, that which is stressed) vocal style. This formal pattern repeats for the sung portion of the song, which repeats the same stresses and call and response. This mostly uniform formal style throughout the first half of the song suggests a challenge to the naturalized connection between speakers and lyrics. If Lesley Gore’s speaker inflects and inserts a number of tones throughout the original version to neutralize the listener against the main themes of the song, to make the listener submit to the falsity that “That’s the way boys are,” then Y Pants are doing something else. By refusing to sing outside of this monotone, deadpan style, they point to the repetitious, slow death of the original version of the song’s enforced patriarchal heteronormativity. No, that’s not the way boys are. That there is nothing natural about patriarchy, about violence done by men, about heterosexuality even.

By the seventh line, another sonic element comes into play. A scream. And it doesn’t go away. This persistent and unsettling sound is played over the duration of the track, even as the singers fade away into non-sound and the patented toy piano and drum combo that is a Y Pants staple finally arrives. I am interested in what makes this scream unsettling. Is it its slow emergence? Its refusal to go away? Is the scream naturally endowed with a sinister meaning because of its pairing with the content of the song? Before we get there, we should entertain the thought that perhaps the scream is unsettling to us as listeners in and of itself, or as Mladen Dolar writes in his book A Voice and Nothing More, “. . . it means that it means” [3]. One way we can make sense of the scream in the song is through the language of Lacan, who theorizes the scream as a presignifying, presymbolic, or prelingustic voice. Dolar writes on the presignifying voice:

There may be no linguistic features, no binary oppositions, no distinctive traits, except for the overring one: the non-articulate itself becomes a mode of the articulate; the presymbolic acquires its value only through opposition to the symbolic, and is thus laden with significance precisely by virtue of being non-signifying. [4]

This seemingly paradoxical language of the non-articulate being a mode of the articulate follows the logic of the system of semiotics in which a signifier is only identifiable or unique in its difference to other signifiers. However, though a scream belongs to the presymbolic voice, it differs from say a cough, a hiccup, or a sigh. It undergoes a process of transformation according to Lacan, elevating its importance above the other presymbolic voices. As Dolar writes:

. . . the moment the other hears it, the moment it assumes the place of its addressee, the moment the other is provoked and interpellated by it, the moment it responds to it, scream retroactively turns into appeal, it is interpreted, endowed with meaning, it is transformed into a speech addressed to the other, it assumes the first function of speech: to address the other and elicit an answer [5]

And what answer might our scream elicit? To whom does the scream the appeal to? It is necessary to understand that Lacan has two terms for what Dolar here refers to as the “other.” The first is this lowercase other, used here by Dolar, which belongs to the imaginary order. This other is characterized by identification, or misidentification, and a “projection of the ego.” There is also the “big Other,” the ‘O’ capitalized, which is inscribed in the symbolic order. More radically, this Other is the symbolic order itself, which “cannot be assimilated through identification.” It seems that for our purposes, dealing with the Other would yield more answers for how the scream in Y Pants’ cover functions. That Other could extend to us as listeners, who hear and are provoked by the scream in the song, who differentiate ourselves from the screamer. But for Lacan, this proves nearsighted. As he writes, “The Other must first of all be considered a locus, the locus in which speech is constituted” [6]. So that, to invoke ourselves, the listeners as the big Other, as the addressee of the scream, we must recognize ourselves not just as its address, but also as the symbolic order itself in which the scream both comes from and becomes, as that which brings it into meaning.

What is clear amidst this theorizing is that there exists a tension between self and other, between singer and listener. As Dylan Evans writes, in An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, “It is the mother who first occupies the position of the big Other for the child, because it is she who receives the child’s primitive cries and retroactively sanctions them as a particular message [7]. In Lacan’s thought, this situation is referred to as punctuation. Since a child cannot speak using words and can only scream to communicate its needs, it is fully on the mother to endow this scream with meaning. There is no sure way of knowing whether the child means to say they are hungry, thirsty, tired, or in pain through their scream. The mother, the one who listens, must both “receive” and “sanction.” She is a participant in the child’s scream just as much as the child itself. It is through her that the child’s scream becomes. Punctuation “creates the illusion of a fixed meaning” [8]. To say the child is screaming because they are hungry satisfies and alleviates the mother’s anxiety. Her punctuation allows her to fix a meaning to the child’s scream, devoid of their intention. In relation to the Y Pants cover, the listeners who benefit from the system of patriarchy and the social fabric of masculinity, are identified as the Other through this method of punctuation. In an attempt to differentiate themselves from the origin of Y Pants’ scream, in searching for a way to alleviate their anxiety from the persistence of its existence in the song, they punctuate it, fix it with a meaning. But how could men punctuate that alarming sound in any kind of way that does not confront the scream itself, and ultimately, the origin of that scream?

And alas, here we are, the listeners ready to search for articulation, ready to obscure a presymbolic sound with meaning. But once more, how can we not read the scream as similar to that of say Rhoda Dakar’s in the 1982 song “The Boiler” featuring the Specials, in which her recounting of a night of being assaulted and raped is punctuated by deafening screams on the track? The screams are those of a woman, no doubt. How can we, the ones interpellated, the ones provoked, the ones addressed, the Object, questioned by the unidentified speaker’s infinite screaming not read it in relation to and antagonization of the heterosexual and masculine universal–namely, violence? What becomes articulate is very clear for anyone listening. The way boys are conditioned to be is built on keeping women silent in relationships, in gross exaggerations of hysteria, in false characterizations and labeling of ‘crazy women,’ and in violence toward women (not necessarily physical). I call the scream infinite because it seems that it goes on even after the 3 and a half minute song is over. It appears as though it could go on forever. This gesture towards the infinitesimal disassembles any linguistic, signifying, or symbolic falsity that holds in place the way boys are, it ruptures this universal through sound which upholds masculinity and allows men to continue being men. To be a man is to hear that scream and know that it unsettles you because you identify as a man. The definition of “boy” or “man” encompasses the production of and participation in violence, and by fixing the meaning of the scream elsewhere, this identity is reaffirmed and bolstered. But Y Pants make it really difficult to do that. In contrast to Gore’s inflections, and in combination with the deadpan non-beauty of the voices in the first half of the song, the scream overturns the metaphor of a masculinist vision and offers instead a grotesque and realistic language. The scream explodes the original version into shards.

2. I Put a Spell On You – Diamanda Galás

To hear Galás, is not to encounter a description of horror but to experience an incarnation of it. In Galás’s work this incarnation is of a number of different bodies constructed as horrible by culture and made to endure the horrible effects of that construction, made to suffer its oppression. — Nicholas Chare, The Grain of The Interview: Introducing Diamanda Galás

There is that infamous scene in Andrzej Żuławski’s 1981 nightmare Possession in which Isabelle Adjani’s character recalls the time she takes the empty subway route home from church with her bag of groceries in hand only to spill its contents everywhere, to drench her lovely blue gown and tights in milk and juice, mixing with the contents of some unnameable fused liquid which comes from her mouth and travels down her legs. It is a traumatic scene whose haunting elements, for me, are localized through Adjani’s mouth and vocal productions. She is first seized with hysteric laughter–the breathy big laughs and the ripply bourgie ones. In a blurred moment, the laughs turn to screams — those infant screams where, if you knew nothing about babies, you would think someone was stealing the soul of the poor crying child. Adjani places her hands on her head like another pair of ears or horns and performs a myriad of short and sustained chest bursts, twisting and thrashing her head and her milk drenched hair in a wild incantation. This goes on for a while, this growl, this throaty concerto. Then come the screeches, the high pitched shrills of beauty which accompany Adjani rolling around in the dried milk which actually looks like chunky yogurt now. Next come the gulpy, choking and muffled sounds, punctuated finally by the loudest and most perfect of blood curdling screams, of which we get two.

I retrace this entire scene in sound-oriented detail because Adjani’s vocal performance prefaces in many ways the work of Diamanda Galás. Watching Adjani in this long scene, we as viewers feel as though we are “experiencing” her explosion, not simply that we are “encountering” it. Someone who merely encounters Adjani here might be able to glance toward what is happening and continue down the empty subterranean halls- they are afforded this agency. But the camera, which locks, fixes and attaches the viewer to Adjani’s mental state and physical manifestation of it, causes us to experience it with her. For over three minutes we must sit with her uncomfortably or cathartically (or both). We must register the necessity for such a scene, not merely as an overdrawn exposé, as just noise, but as a scene with deep implications for this character and her relationships. Adjani here and Galás’ work overall, point to this radical appeal. This is not only because of the multiplicity of voices or “bodies” that Adjani produces, which is central to Galás’ crafted technique, but also because of the political implications at stake. What if the sounds that Isabelle Adjani makes weren’t pathologized as the meaningless screams of the hysterical, the crazy, the mad-woman? What if these sounds were completely intelligible in their unintelligibility, following a logic of necessity? This question is explored and ultimately proven true in the work of Diamanda Galás.

Here, she covers the 1956 classic, “I Put a Spell On You” by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. The song would transform Hawkins forever. Prior to recording, as legend has it, he was just Jay Hawkins, but after a night of good chicken and a lot of liquor, the version that we know now somehow became so. According to Hawkins in fact, he had intended the song to be an ordinary blues ballad, but in a lost drunken moment, instead, a “weird,” strange and sinister track was conceived. The producers promoted the track, but the song received little to no play on the radio. Its voodoo associations, its raw sexual overtones, and Hawkins’ unleashed voice lead to the song being banned on many airwaves. Hawkins, whose foster parents were Blackhawk Indians living in Ohio, estranged himself on stage as well. His live performances of “I Put a Spell on You” were theatrical hallucinations, pre-rock ‘n’ roll arena transformative happenings. Hawkins would perform dressed in Voodoo garbs, with a fake mustache, a tambourine, and a skull on a stick. He would use smoke machines and rise from a staged death out of a coffin. In other words, he would reinvent himself. On stage it was not Jay Hawkins but Screamin’ Jay Hawkins truly, that figure birthed out of the inebriation of a chance recording session.

But it is the screaming nature of his recorded classic, “I Put a Spell On You”–the forbidden aura of its performance, the shock of a black blues singer producing what the greater American audience deemed noise, savage, unlistenable–this is what I’d like to consider. Because it is Hawkins’ voices which cannot be detached from his blackness. Similarly but not equatable to Diamanda Galás, he creates a multiplicity of attached bodies, received first by audiences through the seemingly inescapable physical categories of “black” and “woman.” As Hawkins told the L.A. Times in the early ‘90s on his voice, “I didn’t have the best voice for blues and R&B,” he recalls. “But I could scream. I called on my opera training. I can scream soprano–like a woman.” [9] This ability to scream soprano “like a woman” in his words is the desired effect of the castrati, a brutal 16th-century technique applied to prepubescent boys so that men didn’t have to hear women in the performance halls. The horrid process of the mechanical dreams of the castrati is bypassed here by Hawkins’ “opera training.” He relates that he can “scream” soprano like a woman, choosing this verb as opposed to sing. This suggests the perceived inability of men to achieve the sounds that a woman’s voice can produce. Of course, this claim is based on a binaristic conception of gender in which a clearly defined voice of man stands in opposition to a clearly defined voice of woman.

For Galás, these distinctions between man and woman are moot. By the ‘90s she already had, for more than a decade, transversed beyond the tepid limits of the ‘female voice.’ On her first album alone, “The Litanies of Satan,” she summoned the voices and ghosts of Baudelaire and all who recite his poetry aloud. Like Hawkins, she trained as a youth in the opera, which makes sense when you hear both of their approaches to singing. One of the things that most people who are repulsed by free jazz don’t understand is that the logic of sounds produced by say Anthony Braxton aren’t random, cannot be reduced to noodling or be rendered pointless. To get to a point where you can manipulate an instrument in such a way that does not adhere to conventional form and scale patterns, one has to have a virtuoso understanding of the instrument and patterns they are undoing. Galás is a vocal virtuoso. Every sound that comes out of her mouth has its point, though the notes she sings may at first appear incomprehensible in their extended force. To shed any kind of technicality in music of her force, one has to be technically sound.

This force which Galás engages with is felt in every moment of Hawkins’ original: his laughs, his hysteric screams, the repeating of vocal lines, such as “I love you,” which suggests the singers’ overwhelming infatuation with their love object, and the exaggerated aspiration of the ‘p’ on “I put a spell on you.” It is not the merely the voice, but the instrumentation which differentiates Hawkins’ and Galás’ approaches to the song. In Hawkins’ track, his vocals are accompanied by a very neat drum and horn combo which move up and down a repetitive scale. The only point at which this orderly frame breaks away is in the saxophone solo, but otherwise Hawkins’ outbursts are anchored in the backing instruments. On the other hand, Galás’ cover features a piano only, one which toys with the idea of anchoring her trilling howls, but often appears to crumble away and morph into some other sinister sound. She bangs on the piano hard to begin, playing around and through the original’s reserved instrumentals with chords that linger like a deep wound. This moves into a walking blues bassline, locking in place for as long as she takes to finish the thought (a high pitched shrill from the chest). The time signature switches back and forth as she sings the verses, but drags out into timelessness as she shrieks louder and louder and leaves behind the lyrics. What first appears chaotic, though, actually follows a logic. When the time of her piano changes, so does her voice. Repetitions appear both in her playing and her singing, reacting to each other in an [un]controlled harmony. Repeating lines like “I can’t stand it! I can’t stand it! Can’t stand it!” are met with repeating notes on the piano–the assault of a high and low chord combo. When she sings, “Stop it! Stop it! Stop it!” we hear the same chord echoed on the piano. Galás is not only able to sustain a flux of notes in her intense screams, but if the listener is attentive, they will hear time and again how she restates these sounds, just as she uses words. She achieves this heightened form of legibility through a technique originating in German Expressionist theater called Schrei, meaning ‘scream.’ As Galás notes in an interview, in the articulation of this technique:

. . . movement was oral and the sound was corporeal. The idea was that the spoken word and gesture were one . . . the words were springboards for extreme mental states. In some cases, there were few words but the actor was expected to do a hell of a lot with those few words. [10]

Galás indeed, on this cover and on every track she has produced does a “hell of a lot” with “few words.” It may first be tempting to see what she describes as a reversal. Namely how in the production of schrei, movement becomes oral and sound corporeal. This would be a reversal because it is normally movement which is located in the body visually, and sound which is bound up orally. This assertion is complicated in her next line, how in schrei, the spoken word and gesture are one. This unification allows what Galás calls “extreme mental states” to be expressed. Mental states like frenzy, obsession, mania, and possession–all apparent in the original DNA of Hawkins’ version and her shrieks on “I Put a Spell on You.” These become comprehensible when considering her articulation of this technique. One cannot see frenzy or obsession on or in a song. But they can feel it in their bodies from the force of Galás and Hawkins’ voices. Even the lyrics do not express fully the mental state conveyed in the track. Hawkins used huffs and screams, these noises wrapped up in the forbidden, to emit that which could not be emitted in words. Again here, we find a politics of anchoring at play–just as the instrumentals appear to make presentable the noise, so too do the words. For if it were not for the instrumentals and the lyrics, we would just be left with noise, but if it were not for the shrieks and the screams, the mental states which Galás discusses could not be felt and fully realized. Her shrieks make palpable the feelings which drive the force of the song.

Galás channels and translates the sounds made by Hawkins not as a form of homage but as a matter of expanding the sonic material already present, thus creating new material. Like Isabelle Adjani in that famous subway scene in Possession, she corrodes the distinction between the gesture and the voice, by locating it in the voice completely. We don’t need the flailing of arms, the open mouth, the milky red substance bursting from between a pair of tights to reason that there is a link between that which appears unlistenable and incomprehensible- namely, noise- and the oppressed, disposable body. Galás seeks to move beyond the masculine paranoia and the obsessive possessiveness inherent in Hawkins’ original by, to return to Adjani, experiencing rather than encountering that sonic material. When she comes into contact with this material, these social relations used by men to keep women’s concerns internal and silent, there is no possibility for a passive engagement with it, only one that is active and reactive. Galás becomes the possessive and the paranoid. She experiences these states that her body must burden through this [in]voluntary contact, and translates that which cannot be experienced by some [men], comprehensibly.

Works Cited

[1] Ingeborg Bachmann. Malina: A Novel. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999. Print. 118.

[2] Greil Marcus. In the Fascist Bathroom: Punk in Pop Music : 1977-1992. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001. Print. 217.

[3] Mladen Dolar. A Voice and Nothing More. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2006. Print. 25.

[4] Ibid., pg.24

[5] Ibid., pg.27

[6] Jacques Lacan, Jacques-Alain Miller, and Russell Grigg. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. New York: Norton, 1997. Print. 274.

[7] Dylan Evans. An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge, 2006. Print. 133.

[8] Ibid., pg.157

[9] Dennis Hunt. “The Return of a Legendary Screamer : Pop Music: Screamin’ Jay Hawkins Says He’s Dissatisfied with His New Album, His First since 1974. He Headlines the Palomino on Saturday.” Los Angeles Times, Ross Levinsohn, 2 Aug. 1991, articles.latimes.com/1991-08-02/entertainment/ca-197_1_screamin-jay-hawkins.

[10] Michael, Guillen. “ SCHREI 27: Interview With Diamanda Galás.” ScreenAnarchy, 15 Apr. 2011, 11:10 p.m., screenanarchy.com/2011/04/schrei-27-interview-with-diamanda-Galás.html.